The Western Arctic Caribou herd in Alaska has shrunk by an estimated 23% over the past couple of years. For Alaskan communities that depend on an abundant caribou herd for their very existence, this is a major wake-up call that says better management is needed. For nonresident Alaska caribou hunters, it could be “last call.”

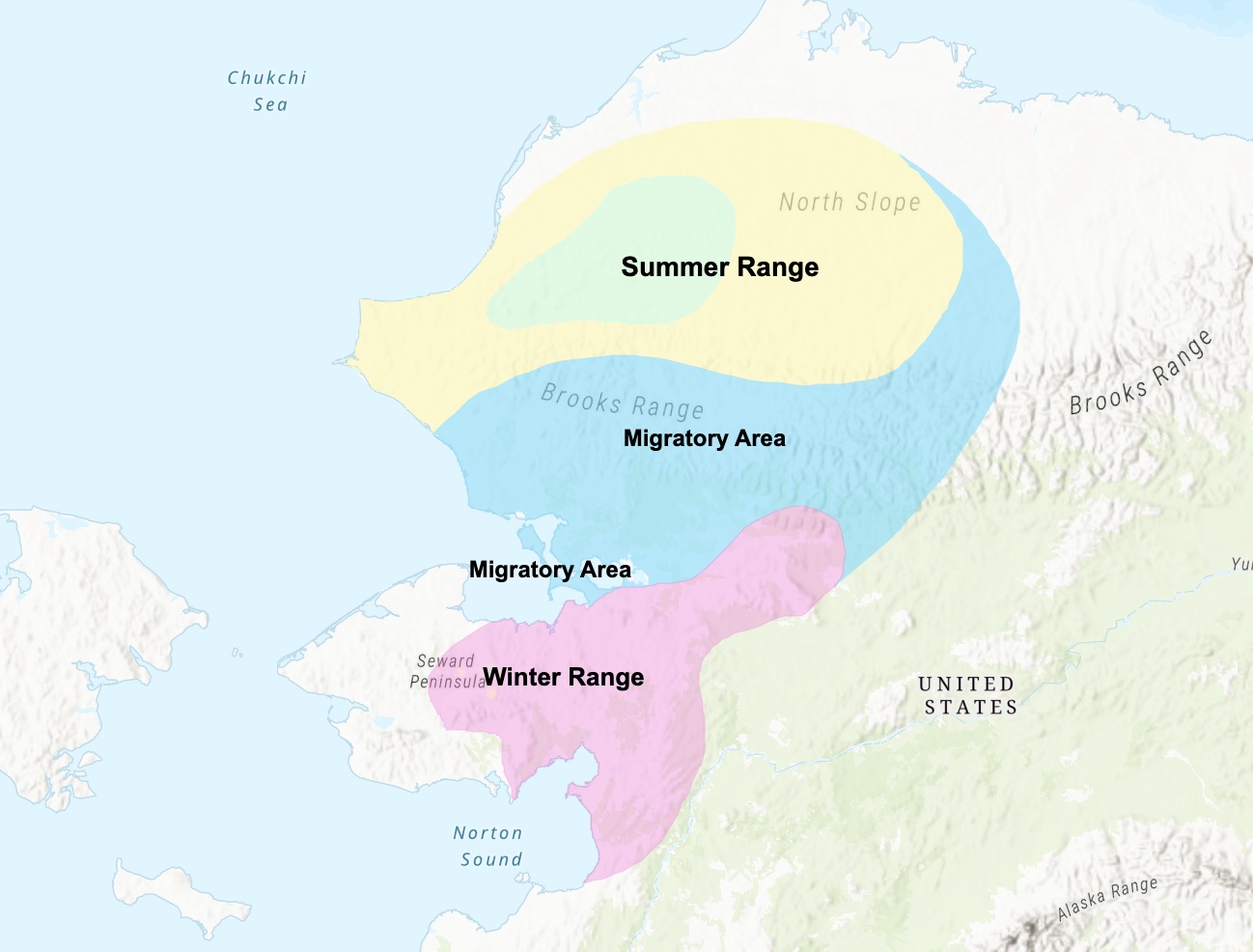

According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the herd is down to an estimated 188,000 animals that range over a nearly 157,000-square-mile area in northwest Alaska. This is the first time the herd’s population has dipped below 200,000 since 1982.

Additionally, the percentage of cows that survived on average over the 2017-2020 time period was 73%, which is below a long-term average of 81%.

In a recent annual meeting, the Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group changed the herd management status from “conservative declining” to “preservative declining” because of the further population dip.

Related: Alaska Woman Shoots Record Caribou on Solo Hunt 4 Months After Bear Attack

The group, composed of subsistence users, other Alaskan hunters, reindeer herders, hunting guides, transporters, and conservationists, recommends caribou herd conservation and management policy in Alaska.

Wildlife biologists informed the group that the three main contributing factors to the decline in the Alaska caribou population are increased predation, hunting pressures, and changing weather patterns.

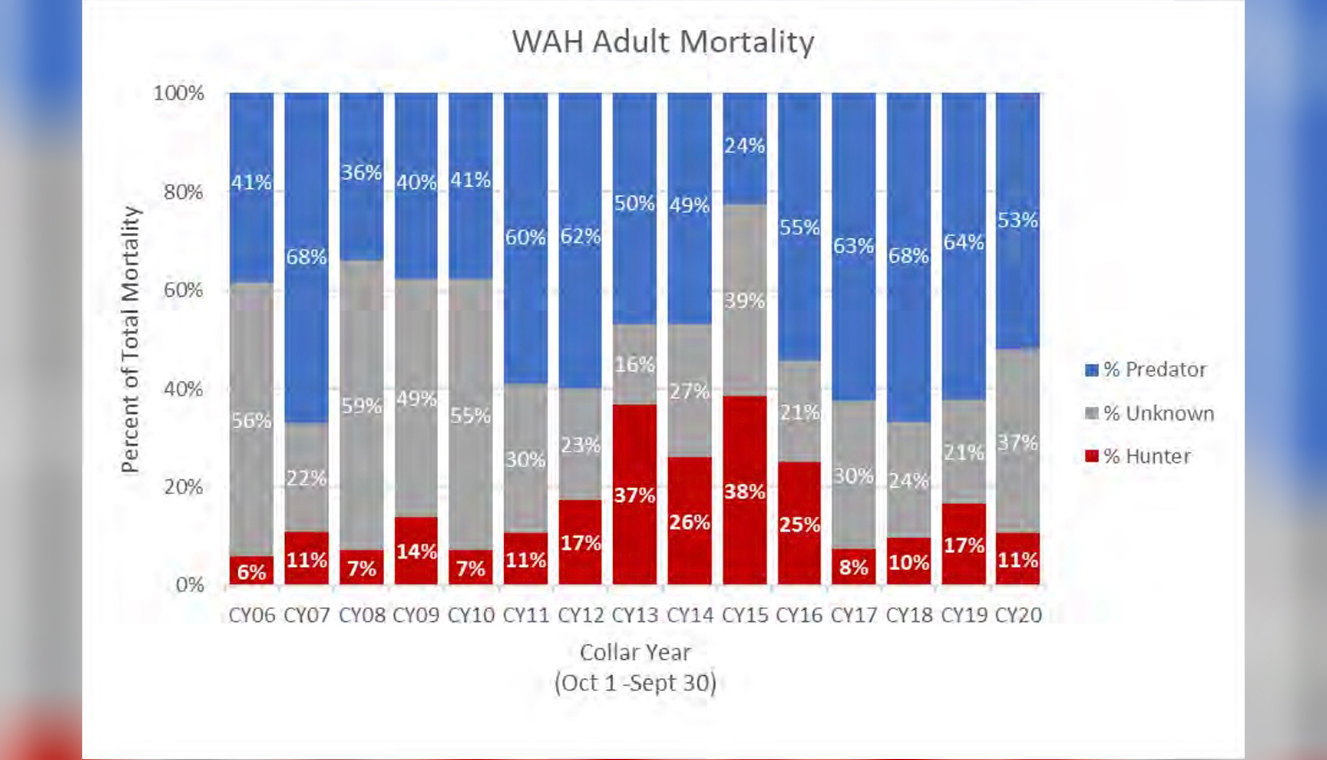

In 2020, predation made up the largest percentage of caribou mortality at 53%. Hunting accounted for 11%. The remaining 37% is labeled as “unknown” but likely includes changing weather patterns and mining infrastructure.

Additionally, the changing climate has had a significant impact on the herd’s migration. Caribou usually arrive in northwest Alaska in September but didn’t appear until late November this year.

Kyle Joly, a National Park Service wildlife biologist, explained how progressively milder fall and winter weather is affecting herd migration.

Related: DIY Alaska Caribou Hunt Checklist: How to Hunt the Dalton Highway

“A drop in temperature and a dump of snow really drives caribou, and they can go really, really far really fast during those episodes,” Joly said in the meeting. “If they come across better terrain, less snow, better forage, they’ll slow down. These are important implications related to climate change because we’re seeing much warmer temperatures and much later snowfall in the fall.”

With only so many levers to pull when it comes to mitigating herd decline, the herd’s status change will most likely lead to more hunting restrictions in the future.

Under current restrictions, in parts of northwest Alaska — specifically, Game Management Unit 23 — residents can kill five bulls or calves at any time of year. Hunting cows is limited to a seven-month season. Nonresident hunters can kill one bull per year from August through September.

Related: The 7 Oldest Pope & Young Archery Records

Under the “Preservative Management” status, hunting regs could be changed to include: no killing of calves, limiting the killing of cows by residents through permit hunts and/or village quotas, limiting the subsistence hunting of bulls only if there are less than 30 bulls per 100 cows, restricting caribou hunting to Alaska residents only, and closing some federal public lands.

Alex Hansen, a Fish and Game wildlife biologist, said the harvest rate for local hunters is about 12,000 caribou, which equates to roughly half of the total caribou killed in the state. Non-local hunters, including nonresidents, get about 250 to 300 caribou annually, depending on the year.

He added that state game managers might find it difficult to decide on hunting restrictions because reporting in the area is limited. Fish and Game officials only capture a small percentage of that data because most hunters don’t have a permit, Hansen explained.

“We realize that the permit requirement is fairly new, and we will continue to work with hunters and communities to improve compliance,” he said. “The people of Northwest Alaska depend heavily on caribou, and reporting their catch each year is a simple way they can ensure the viability of the herd for their children and grandchildren.”

Meanwhile, the Federal Subsistence Board has a wildlife regulatory meeting scheduled for April. The board already plans to consider caribou hunting closures for people living outside the range.

Hansen said that hunt closures for nonresidents would strictly target bulls and won’t be enough to bring meaningful change. He added that restrictions on cows might have to be tightened in the future because cows are the drivers of the population.

This isn’t the first caribou herd to experience a significant decline in numbers. The Quebec/Labrador caribou occupies the largest area of land of all caribou species (an estimated 600,000 acres), with animals trekking up to 3,000 miles during migration. Unfortunately, their population crashed to 1% of its healthy numbers, and a moratorium on hunting was put in place in 2017 to protect the remaining herd.

One thing is for sure: Unless all parties involved work together to figure out the root source of the decline and proactively manage the herd for future generations, the Western Arctic Caribou could face the same fate.

Read Next: Prime Alaska Caribou Hunting Units Could be Closed

Comments