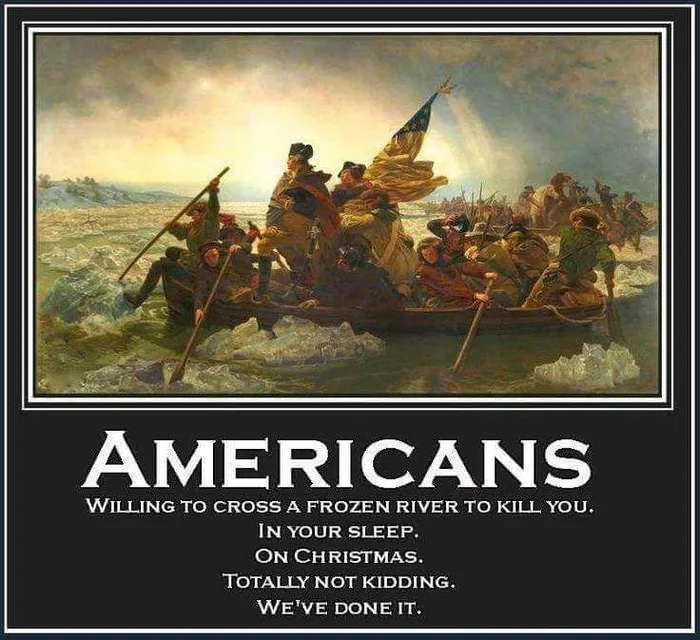

Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 painting, Washington Crossing the Delaware, is undoubtedly one of the most “America, fuck yeah!” paintings that depict any part of the American Revolution.

In recent years, the painting of George Washington crossing the Delaware River in the Christmas cold, currency housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, has been co-opted by the meme community to sum up the historic event in a few patriotic-if-simplistic lines: “Americans: Willing to cross a frozen river to kill you. In your sleep. On Christmas. Totally not kidding. We’ve done it.”

While all that conjures up a completely badass picture of Gen. Washington and the determination of his troops piled into Durham boats, it’s not an accurate summation of what happened that night and why. Washington and his men did cross the Delaware River in the middle of the night on Christmas to kill the Hessian forces on the other side — but not because it was an amazingly foolproof plan. Washington opted for this kind of attack because he had no other choice.

Rough Start for the Revolution

While we tend to remember 1776 as an amazing year highlighted by the signing of the Declaration of Independence that summer, the reality is that the year was hardly a resounding success for Americans.

As 1776 drew to a close in mid-December, Gen. Washington and his soldiers were at a low point, and the American Revolutionary War wasn’t going well for the Continental Army. They had been defeated at New York City, forced to retreat through New Jersey, and found themselves encamped back in Pennsylvania along the Delaware River as winter set in hard.

The soldiers had been repeatedly defeated; it was getting increasingly colder, clothing was worn thin, and food was in short supply. The Continental soldiers were feeling pretty damn miserable at this point. For many, the only glimmer of hope was that their enlistments would be up come January 1777, and they could put this whole soldiering mess behind them. Washington knew that he needed to do something to help boost the morale of his men and try to end the year on a high note.

RELATED: Oliver Winchester and Sam Colt – Innovators and Lousy Gunmakers

He figured a surprise attack against a garrison of approximately 1,400 Hessian mercenaries near Trenton, New Jersey ought to do the trick. If they could pull off a quick victory there, the men’s spirits would be lifted, and it might encourage enlistment of new soldiers the following year. After meetings and counseling with his officers, Washington decided to attack Christmas night into the morning of Dec. 26.

Obstacle After Obstacle

The stealthy crossing was nearly foiled from the start.

Almost as soon as the plan was decided, word of the impending attack was leaked to the Hessians by a British spy in Washington’s ranks, who was never identified, and by two Continental deserters. Thanks to a series of false reports of previous attacks, the awful weather closing in on Christmas night, and the fact that the Hessians were a cocky bunch, they didn’t adequately prepare, despite the warnings.

Around 6 p.m., the daring plan was set into motion, but the weather had taken an abysmal turn. Winds howled out of the northeast carrying sleet and snow with it, temperatures hovered around 30 degrees, and the Delaware River became choked with ice. In short, the crossing would be no cakewalk, and victory was far from assured.

A large portion of Washington’s men crossed the river in Durham boats, which were larger than Leutze’s painting depicts — they were 40 to 60 feet long, 6 feet wide, and 3 feet deep with flat bottoms, and weighed thousands of pounds. They were pointed at both ends and designed to travel up and down the river hauling cargo. They were propelled along the shoreline by plating steel-tipped poles in the riverbed and oars were used in deeper water. The boats took some skill to steer, even in good weather.

The plan suffered some serious blows early on, in addition to the leak. There were supposed to be three separate crossings, but two of them were unable to make it across due to the river ice. Only the group that included Washington himself would actually forge ahead.

RELATED: Hiram Maxim – The Right Place, Right Time, Right Gun to Change History

By the time Washington’s 2,000 men and all their equipment (including 18 cannons) had made it safely across the 300-yard span of the river, they were 3 hours behind schedule. They were across the river, in New Jersey, but they still had to march 10 miles north to Trenton to carry out the attack. Due to the weather, it took 4 hours for the Continentals to get to Trenton.

Attack on Boxing Day

Despite the difficulties and delays, Washington and his men made it to Trenton and still managed to surprise the garrison of Hessians right around daybreak. A running fight through the town ensued with all but a handful of the Hessians being captured by the Continental soldiers.

The success of the surprise attack is evident in the numbers: The Continentals suffered just five casualties, none of them fatal. The Hessians endured 905 casualties, with 22 killed, 83 wounded, and an astounding 800 men captured.

It wasn’t just the Hessians and their immediate command’s unpreparedness that ultimately led to the Continental victory at the Battle of Trenton. Conventional rules of warfare in the 18th century saw little to no fighting during the coldest months of the year. Troops set up in winter quarters and waited for the weather to warm up before returning to the killing fields. In fact, so sure were the British that no attack would be coming that the commanding general, Lord Charles Cornwallis, had planned to head back to London for the winter!

Of course, his plan changed abruptly with word of the crossing and surprise attack, and General Cornwallis stayed in the colonies. Washington’s unconventional thinking born of being utterly out of alternatives helped secure this significant victory.

Washington and the Continentals were bolstered by their success. They staged yet another crossing of the Delaware just a couple of weeks later, resulting in another American victory during the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777.

RELATED: Photos of What Old West Life Was Really Like in Tombstone, Arizona

The British did not dispute that the Americans had carried the day both at Trenton and Princeton. However, they viewed the victories as minor at best, assuming they would be of little overall consequence during the war.

Instead, Trenton and Princeton proved to be tremendous victories, if not in tactical terms but for the continental morale. Americans saw the crossing and the following battlefield victories as proof positive that they could indeed win this war and secure independence.

Men became less hesitant to enlist or re-enlist, and Congress was determined to make the enlistment expiration scare of 1776 a thing of the past. From 1777 on, enlistments were for three years or the length of the war.

Of course, the road to independence was still fraught with difficulty, and belief in the ultimate victory ebbed and flowed with the news of each battle and the condition of soldier and civilian morale throughout the colonies.

By the time Washington and Cornwallis met on the field of battle for the final time at Yorktown, the war had gone on far longer than either side had ever imagined. On October 19, 1781, Gen. Lord Cornwallis surrendered to Gen. George Washington, signaling the end of the war and the beginning of the United States of America.

Much like Washington surprised the Hessians years earlier during the daring Christmas crossing, he ultimately surprised Cornwallis with the American victory at Yorktown. In the end, the British learned the hard way that Americans were willing to cross a frozen river to kill you. In your sleep. On Christmas. And that we were totally not kidding. We’d done it once before and you can be damn sure we’d do it again.

Read Next: Everything You Know About the Boston Tea Party Is Probably Wrong

Comments