The United States is referred to as “The Land of Opportunity,” and while “opportunity” has long been the focal point of that phrase, there was a time when “land” was the opportunity. On May 20, 1862 — smack dab in the midst of the Civil War — a piece of legislation called the Homestead Act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln.

Under its provisions, legal US citizens and prospective future citizens could lay claim on up to 160 acres of land, provided they were at least 21 years old and that they lived on the claimed land as their established permanent residence for five years. They also had to make improvements to it, and pay a small registration fee to transfer the legal ownership from the federal government.

Related: Everything You Know About the Boston Tea Party Is Probably Wrong

The “Homestead Act of 1862” went into effect at midnight on Jan. 1, 1863, along with the Emancipation Proclamation that freed slaves in states that were in rebellion. That day, Daniel Freeman of Iowa persuaded James Bedford to open up the Brownville, Nebraska, Land Office in the middle of the night so that he could file a claim right away.

The office wasn’t slated to officially open up until Jan. 2, but Freeman, who was a Union soldier on a brief furlough, had been ordered back to St. Louis and wouldn’t be in town to file his claim the following day. Bedford agreed to accommodate Freeman’s unique situation. And so, at 12:10 a.m. 159 years ago, Freeman became the first person to take advantage of the Homestead Act.

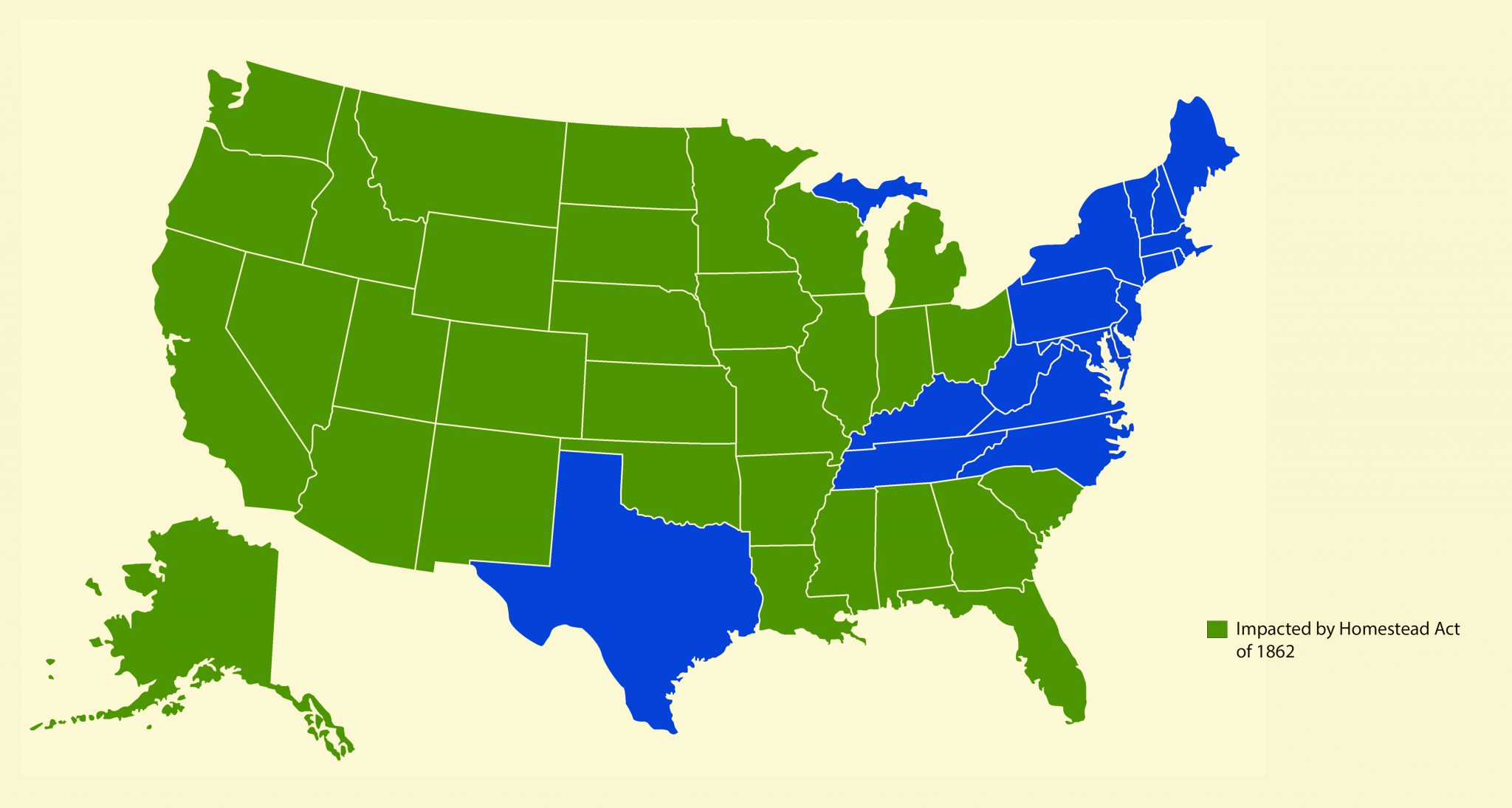

He was joined by 417 other men in filing claims that first day in a foreshadowing of how popular the act would become. All told, a whopping 270 million acres were claimed by homesteaders between 1863 and 1976 when the act was repealed, save for Alaska, where it was extended until 1986. That comes out to a full 10% of the entire United States. It provided, in Lincoln’s words, a “fair chance” for people to make their own way in The Land of Opportunity.

Related: Oliver Winchester and Sam Colt: Innovators and Lousy Gunmakers

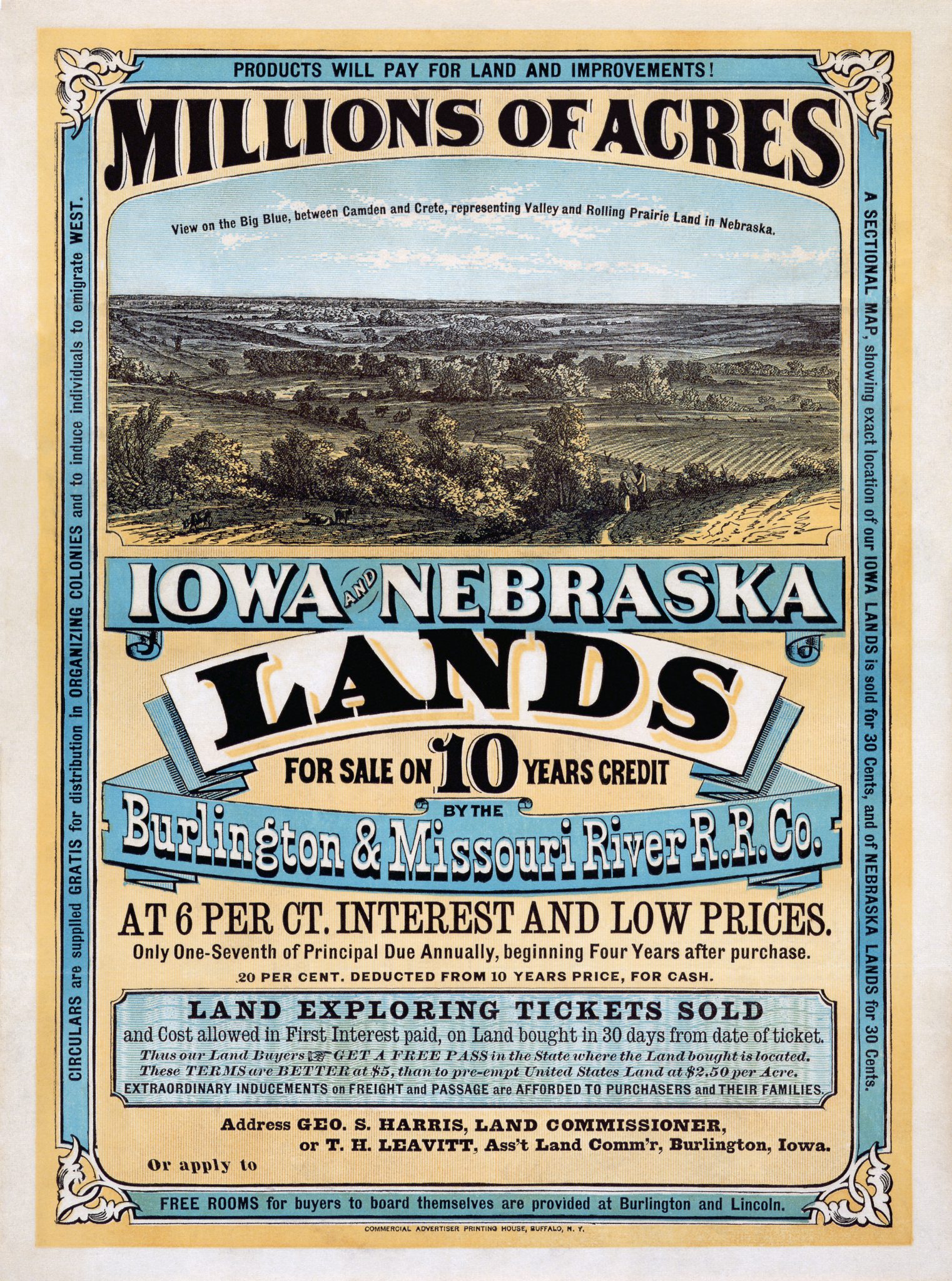

Expansion into the Western portions of North America had been a primary goal dating all the way back to the colonial era when places like Ohio and Kentucky were on the western edge of civilization and people were clamoring to branch out into new, unsettled areas.

As time passed and the concept of Manifest Destiny took hold, the United States’ landholdings stretched all the way to the Pacific Ocean, but the formalization of those lands as part of this new country lagged behind.

Worry about the spread of slavery into these Western lands led to previous versions of the Homestead Act failing three times in the House, and it was killed once by a veto from President James Buchanan in 1860.

Related: Photos: What Old West Life Was Really Like in Tombstone, Arizona

With the Civil War raging and Lincoln’s abolition of slavery in effect, the expansion of King Cotton was no longer a concern, and so that’s why 1863 became the pivotal year for the beginning of homesteading.

A Hard Life and a Lot of Work

While 160 acres may sound like a lot of land — and it was to Easterners at the time — the landscape was far different out West, and many homesteaders would soon discover what worked in one part of the country wouldn’t cut it in another.

Decades before the Dust Bowl ravaged much of middle America, countless homesteaders in those same places discovered it was fairly easy to lay claim to the land, but it would take a tremendous amount of work to tame it.

It was a tough life, and Mother Nature didn’t do anything to make it easier. Locusts, blizzards, prairie fires, tornados, drought, and wind were just some of the many natural hardships the homesteaders would endure.

On top of all that, sparse trees and limited lumber forced many to live in sod houses that were far more primitive than any subpar dwellings they would have encountered back East — even for the time, it was primitive living. Because of these reasons and others, it’s believed that some 60% of all homestead claims were eventually abandoned.

While the act had a provision that reduced the residency requirement from five years to six months, it also required payment of $1.25 per acre to take advantage of the reduction. That comes out to $200 for 160 acres or about $4,400 when adjusted for inflation. In today’s dollars, that’s a hell of a good deal, but in 1863 money, the average laborer made around $300 per year.

Related: Annie Oakley: A Legend Who Taught Thousands of Women to Shoot

That meant the purchase option was out of reach for most, and so they had no choice but to stick it out for the duration. Despite the trials and tribulations, more than a million homesteaders obtained full legal claims to their plots of land.

Homesteaders Came From all Walks of Life

While we tend to think of homesteaders as just a bunch of white guys grabbing up land, the reality was far different. Homesteaders were men, women, formerly enslaved people, and immigrants of all kinds. Women who were single, widowed, divorced, or abandoned could set up claims in their own name, and thousands of them did. Millions of others helped their families in improving the land so that they could fulfill the requirements of the homesteading agreement.

Such was the case for Jeannette Rankin of Montana, who helped improve the 160 acres claimed by her family under the act. She went on to become the first woman elected to the US House of Representatives in 1916, a full four years before women were granted the right to vote under the 19th Amendment.

Moses Speese was born into slavery on a North Carolina plantation in 1838. After the Civil War, he and his wife Susan became sharecroppers, but like many newly-freed enslaved people, they were cheated by the landowners. Despite having members of their family held hostage when they tried to leave, the family eventually made it to Indiana.

Proving only slightly more accomodating than North Carolina, Nebraska became the Speese family’s home in 1880; they filed a homestead claim in 1882 for 158 acres. Taking advantage of the Timber Culture Act of 1873, Moses filed a second claim for 160 acres. When all was said and done, he and his family fulfilled their obligations and paid $3.96 to file paperwork for 316 acres of land.

Many of the immigrants who made their way to the United States during the Civil War and the Indian Wars of the 1870s went immediately into the military. All veterans, native-born or immigrants, were allowed to file claims even if they didn’t meet the age requirement as a special benefit.

Related: Sitting Bull Has Great-Grandson in South Dakota, DNA Test Confirms

Time spent in the service was also allowed to be applied to the residency requirement, reducing the five-year term to as little as one year.

The Consequences of Expansion

While claimants of all kinds enjoyed the opportunity provided by Lincoln’s fair chance, it had unfair consequences to the Native Americans who had inhabited for generations the lands that were now being given away to strange newcomers.

Already adversely impacted by the Indian Appropriations Act of 1851, the Homestead Act of 1862 added insult to injury for the Native Americans who had once called what was now the Eastern US home and had barely begun to establish roots in their new Western lands before being uprooted once again.

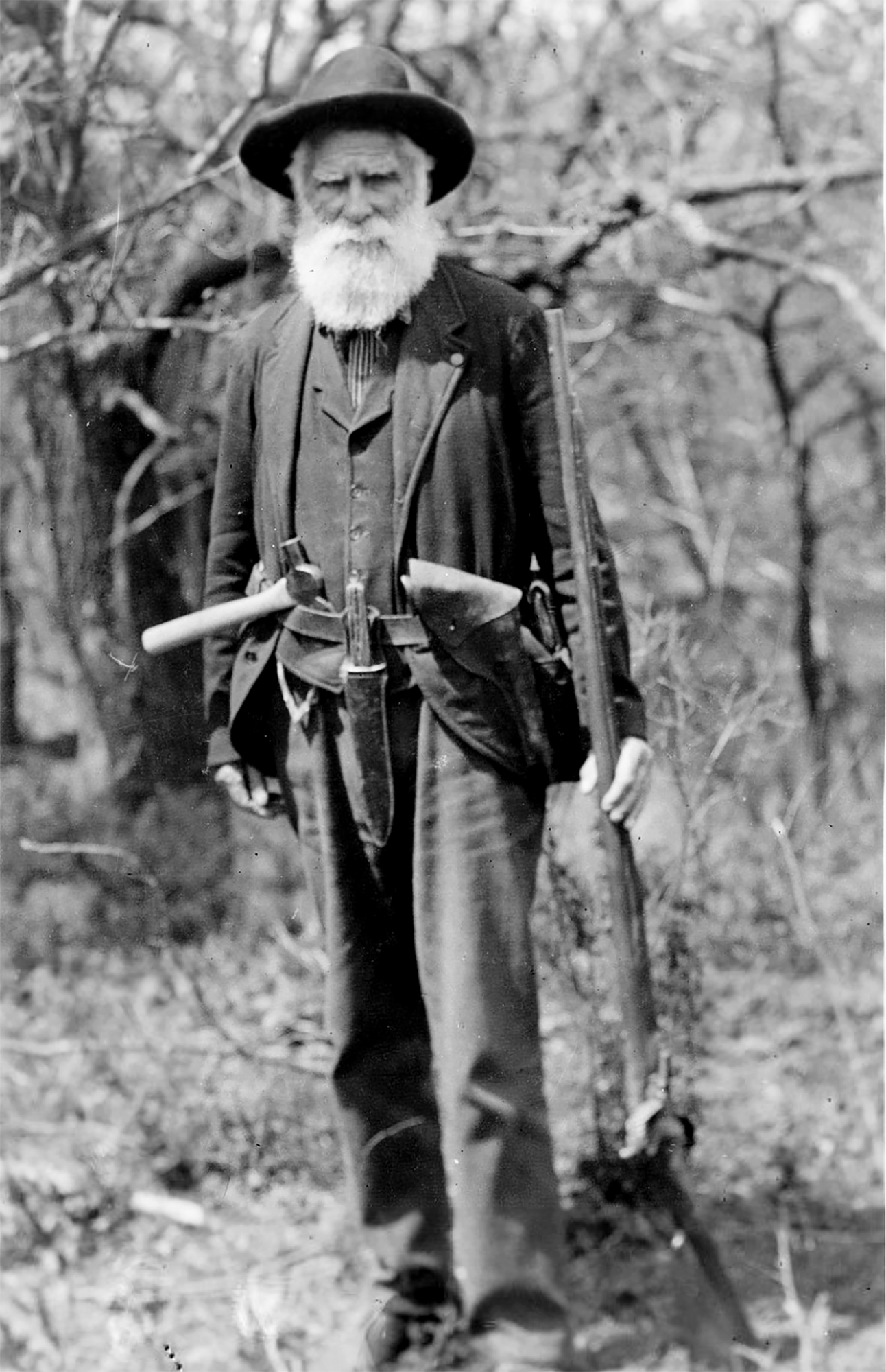

Related: Mountain Man Seth Kinman: A Legendary Hunter With Presidential Pals

Native populations with established roots in these Western lands watched homesteaders irrevocably change the landscape forever. Water sources were diverted, fences were erected, non-native plant species were introduced, and the native wildlife (chiefly the bison) were hunted beyond sustainability.

More land claims and Western migration caused even greater pressure on the Native way of life as the 19th century pressed on and gave way to the 20th. Soon, lands set aside for reservations were divided up even more, and the tribes were left with less and less land each time.

Without a doubt, the treatment of Native Americans is one of the most significant and saddest legacies of the Homestead Act — if not all of American history. But despite the wrongdoings, it remains the history of this nation, and we have to acknowledge it as such, as well as the good that came from the Homestead Act for more than a century.

Daniel Freeman, Jeannette Rankin, and Moses Speese are representative of the million-plus Americans who used the Homestead Act to establish a new American way of life and can-do survival attitude that endures to this day in the Western parts of this country.

Without the Homestead Act, countless lower- and middle-class Americans would never have been able to realize the dream of owning a piece of land to call their own. By the time the act was repealed in the lower 48 in 1976, more than 4 million people had made successful claims in 30 states.

It is rumored that Mark Twain once said, “Buy land, they’re not making it any more.” Whether Americans bought it or claimed it, the sentiment remains the same, as land continues to be one of the cornerstones of the American identity, and no one has, as of yet, created any more.

Read Next: Washington Crossing the Delaware in 1776 Was a Last Resort

Comments