William Clark may be best remembered for his pivotal role as half of the team behind the Lewis and Clark Expedition, but the 30 years of his life that bookended his time with the Corps of Discovery were just as exciting.

In addition to charting a huge expanse of untamed wilderness and helping to extend the reach of the United States to the Pacific, he worked for or with a good handful of US presidents and was a major player during one of the most controversial times in the nation’s history as it grew into the very lands he once explored.

As the 183rd anniversary of Clark’s death approaches, let’s take a look at the extraordinary life led by this legendary explorer.

Too Young for the Revolution

Clark was born in 1770 in Virginia. The ninth of 10 children, he was far too young to fight in the American Revolution and watched his five older brothers go off to war, longing for his own military service. After relocating to Kentucky, Clark joined up with the local militia in 1789 when he was 19. After fighting Native Americans in the Northwest Territory, Clark was commissioned as a militia captain in the Indiana Territory when he was just 20.

When the Legion of the United States was organized in 1792, Clark became a lieutenant of the 4th Brigade under the Revolution’s famed Gen. “Mad Anthony” Wayne. At the same time, a man named Meriwether Lewis was in charge of the 2nd Brigade.

Clark participated in multiple skirmishes and battles, including the Battle at Fallen Timbers in 1794, which helped end the Northwest Indian War.

A New Frontier to Explore

A bout of poor health forced him to resign from the military in 1796 at the ripe old age of 26, but Clark’s adventures were just beginning.

Seven years later, President Thomas Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803 for $15 million. The United States now had 530 million acres of new land within its borders, the vast majority of which was completely unknown and uncharted.

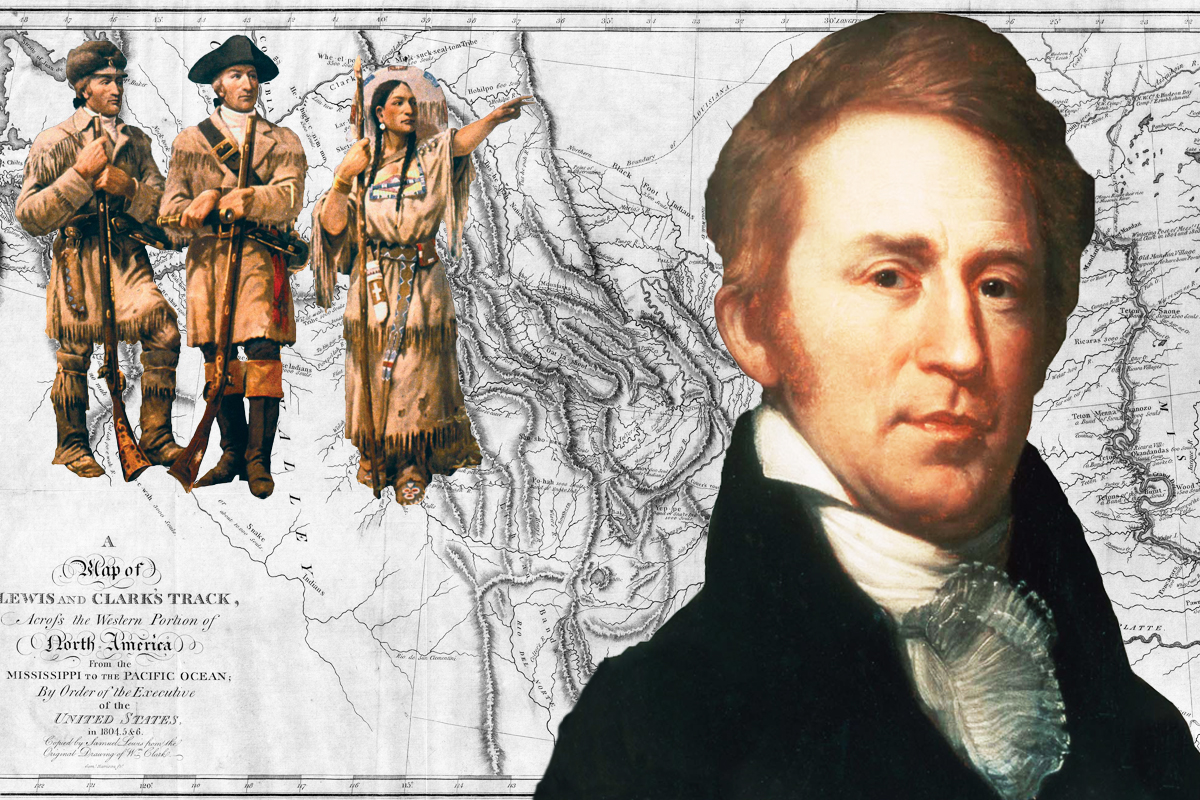

Capt. Meriwether Lewis, Clark’s old friend from the Legion days, chose him to help lead the newly formed Corps of Discovery on an expedition that would last several years, help establish dominance in the newly acquired land, chart the vast area for future exploration, and determine how to best utilize the natural resources found there for the country’s economic benefit.

Lewis wrote to Clark on June 19, 1803, asking him to join the expedition. He respected Clark and believed his abilities as a draftsman and a frontiersman to be greater than his own. Jefferson then lobbied the Secretary of War to make Clark a captain, but the request was refused. Despite being denied equal rank with Lewis, Clark was nonetheless treated as a co-leader of the expedition at Lewis’ insistence, out of respect.

The expedition departed in mid-May of 1804 with a party of 40 to 50 men (records differ on the exact number). Clark selected the men personally, seeking out unmarried soldiers who were healthy with extensive hunting experience and survival skills. The expedition also included a French-Indian interpreter, a hired boat crew, and York, an enslaved person owned by Clark.

Sacagawea, a 16-year-old Lemhi Shoshone woman, famously joined the expedition in what is now North Dakota and traveled with it for thousands of miles, helping Lewis and Clark establish cultural contacts with the native peoples they encountered.

The expedition was heavily laden with supplies, much of it weapons and weapon-related items. Their packing list included 15 rifles, 500 fresh flints, 200 pounds of gunpowder, 400 pounds of lead, as well as 324 knives to be used for bartering with Native Americans they encountered. The most famous weapon in the arsenal was Lewis’ .46-caliber Girandoni air rifle (see video above), now in the collection of the National Museum of the United States Army.

Returning Heroes

It would take the Corps until mid-November of the following year to reach their goal: the Pacific Ocean. Clark estimated the expedition covered 4,162 miles. Amazingly, it was later determined he was off by just 40 miles. By late September 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition had safely returned to St. Louis, Missouri, and was deemed a success. In total, the journey took two years, nine months, and four days.

In addition to exploring and mapping out the new lands with extreme accuracy, Lewis and Clark returned with samples of “exotic” plants and animals from the West, which they also carefully documented. Jefferson was keen on having some of the items, and he established a sort of museum in the main hallway at his home, Monticello.

Superindendent of Indian Affairs

Jefferson gave Clark a government job as a reward for his efforts, putting him in charge of Indian Affairs. He also doubled Clark’s initially promised pay for the expedition, gave him 1,600 acres of land, and appointed the man who could not attain a captain’s commission before he left for the West as brigadier general of the new territory’s militia.

In 1813, Clark became Governor of the Missouri Territory at the behest of President James Madison. He held that position until 1820 when he lost the vote in the new state of Missouri’s first gubernatorial election. Still, the government recognized his importance in politics on the Western frontier, and President James Monroe made him Superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1822.

A decade later, under President Andrew Jackson, Clark oversaw and executed many of the president’s controversial Indian removal policies in that position. This resulted in the Black Hawk War of 1832, which included the military service of future presidents: Zachary Taylor and Abraham Lincoln.

Clark oversaw 10% of all treaties executed between the United States and Native Americans during his tenure as superintendent. Personally, Clark preferred Jefferson’s earlier plans of assimilation, but he had to acquiesce to Jackson’s removal agenda now that he occupied the Oval Office. As a result, millions of acres of land, many of which Clark had traversed decades earlier with Lewis, were stripped from the native populations and brought under the control of the US government.

On Sept. 1, 1838, William Clark died at the age of 68 in St. Louis, which is fittingly known as the “Gateway to the West.” It is said that the entire city went into mourning and that his funeral procession was more than a mile long.

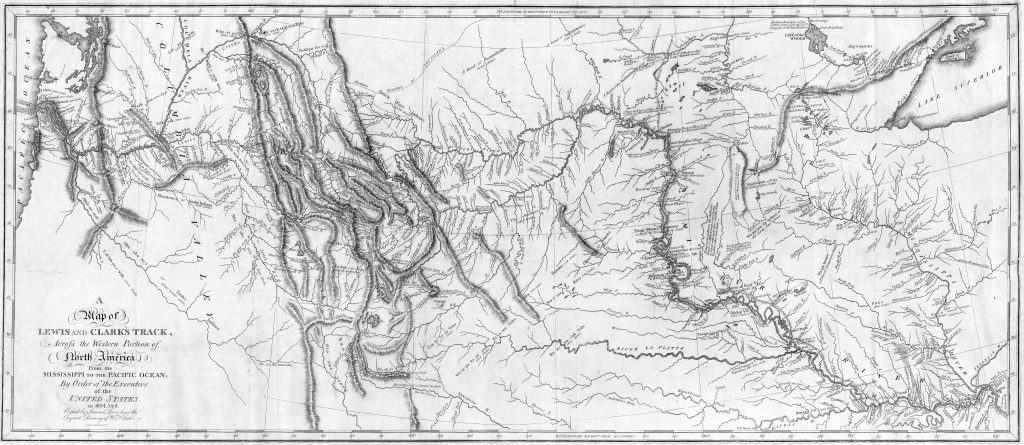

The expedition Clark helped lead is regarded as one of the most successful in American history and it significantly contributed to the geographic and scientific knowledge of the West. Clark’s maps of the region’s geography were printed in 1810 and 1814 — they were the best available until the 1840s.

Righting a 198-year-old wrong, President Bill Clinton finally bestowed the posthumous rank of captain on William Clark in 2000.

Clark’s contributions to the United States’ successful western expansion have been honored in many ways. He has been featured on commemorative coins and postage stamps, and six counties, multiple schools, a river, two Naval vessels, and more are all named for him.

Read Next: Backcountry Flyers: 6 Classic Bush Planes That Get Us Out There

Comments