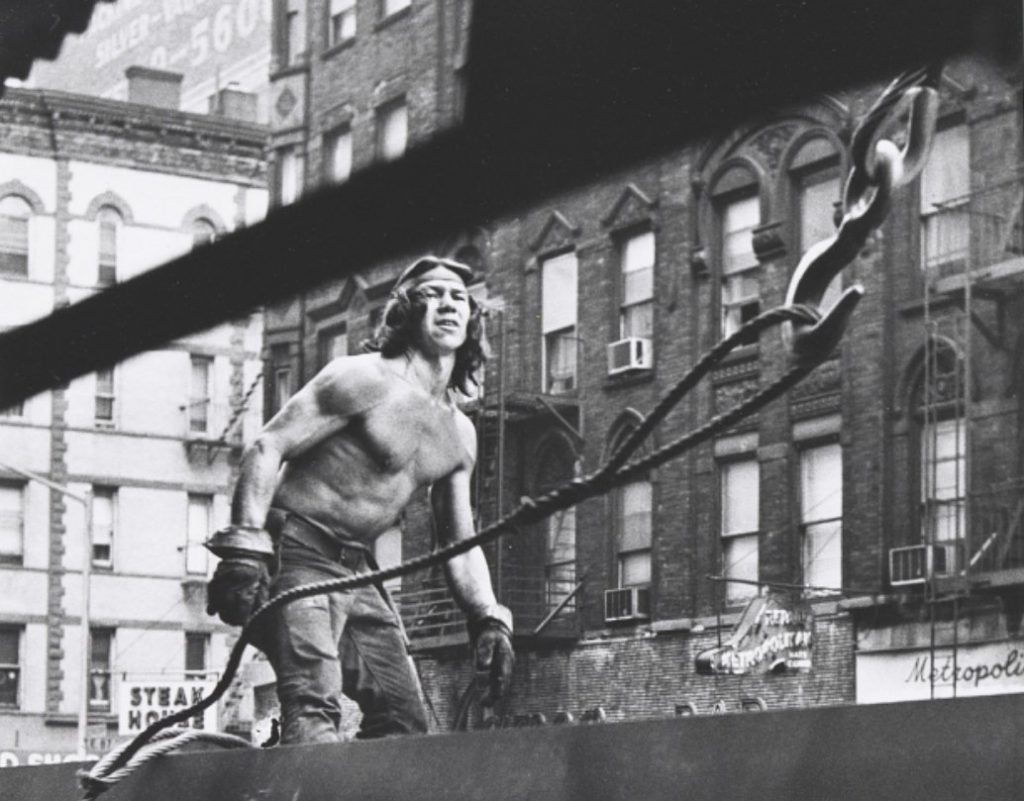

The best part of ironworking is the view. At least that’s what the men who fearlessly live their lives on the beam have said. For most onlookers, scaling the skeleton of a skyscraper that reaches 1,400 feet above the pavement may seem death-defying, but for these unsung heroes of construction known as cowboys of the sky, it’s just another day on the job.

Since the late 1880s, when the first steel-framed skyscrapers emerged, ironworkers have been responsible for changing the skylines of New York City, Chicago, Dallas, San Francisco, and every other major metropolis across the United States and around the world. The boom was spurred in part because of the serious fires in major American cities made of wood.

The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 was a two-day burn that destroyed thousands of wooden buildings, killed 300 people, and caused an estimated $4.8 billion in damages. The following year, the Great Boston Fire of 1872 destroyed 776 buildings across 65 acres of land with a combined loss of $1.5 billion. Architects searched for other means to fireproof buildings, and soon American cities were transformed in steel.

William Le Baron Jenney, an architect said to be responsible for designing the world’s first skyscraper in Chicago in 1885, gets a lot of the credit. In some history books, it is as if he single-handedly erected the Home Insurance Building, with no mention of the unnamed ironworkers. But in truth it was the unknown blue-collar Americans who moved to work in New York City that made the transformation happen.

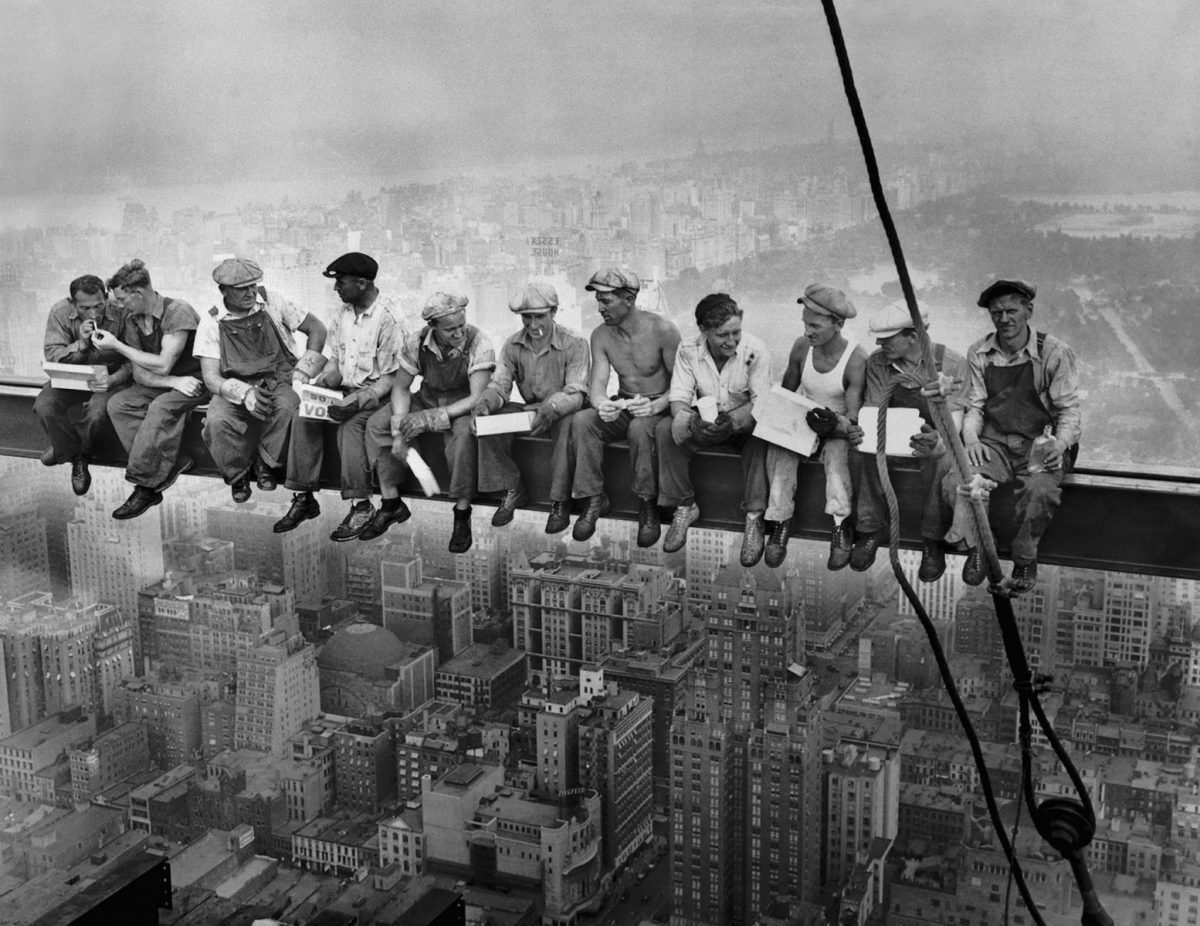

A photographer, later revealed as Charles C. Ebbets, took a photograph (top) known as “Lunch Atop a Skyscraper” on Sept. 20, 1932. It showed 11 men without safety harnesses joking and smoking cigarettes, with one gentleman farthest on the right holding what appears to be a near-empty bottle of whiskey. The photo captured the essence of ironworkers as they sat seemingly unfazed as they ate lunch 840 feet above 41st Street during the construction of 30 Rockefeller Plaza in Manhattan.

The truth behind the picture isn’t exactly what it seems. The image was a staged photo taken on the 69th floor of the flagship RCA Building, now called the GE Building. The photo served as a part of a promotional campaign for the new and enormous skyscraper complex. The ironworkers in the picture remained anonymous for years until Irish filmmaker Seán Ó Cualáin released a documentary called Men at Lunch in 2012. While at a pub in Galway, he noticed a note beside a photograph. On it was a message that revealed the identities of two of the ironworkers.

“This is my dad on the far right and my uncle-in-law on the far left,” the note said, according to Ó Cualáin. They asked the bartender about the note, and he put them in contact with Pat Glynn, the son of a local immigrant who left Ireland for New York in the 1920s, who confirmed the story.

At the turn of the 20th century, one in seven died on the job.

“We do not die,” said an early motto, according to The New York Times, “we are killed.”

For many ironworkers, it was a family business where third- and fourth-generation workers could recall stories about their grandfathers or great-grandfathers who built the kingdom of steel in New York City. They weren’t all Irish immigrants, either. A small Indian community in Quebec known as the Mohawks of the Kahnawake (ga-nuh-WAH-gay) had men on every major skyscraper and bridge project in New York through the first half of the 20th century.

Native American ironworkers were present when the World Trade Center was erected and joined other original ironworkers at Ground Zero when the Twin Towers fell after the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001.

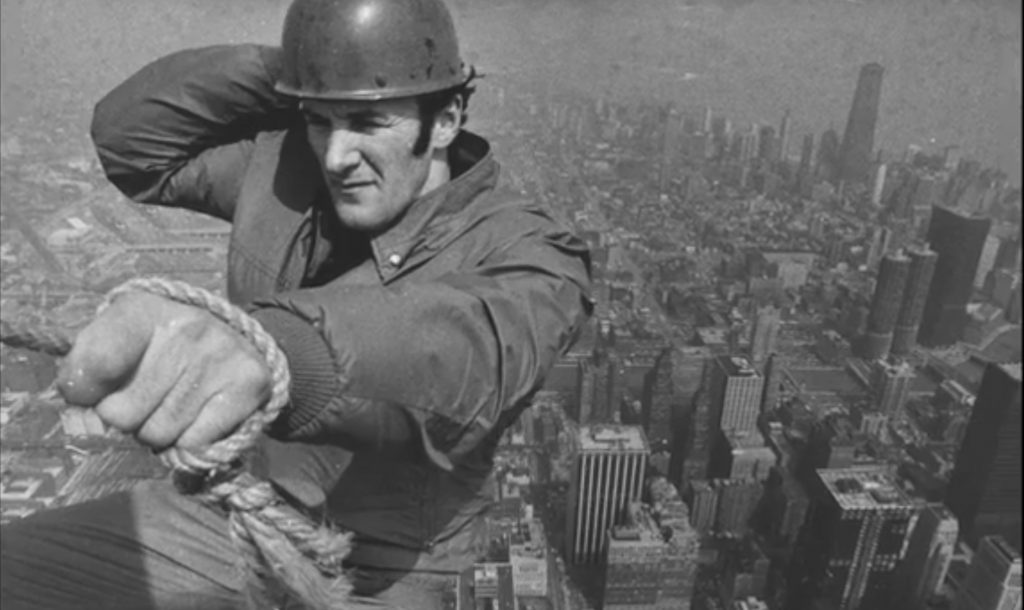

Some ironworkers can’t give up the thrill of climbing toward the sky, even after their careers are over. John Rukavina, a semiretired ironworker whose career began in the 1960s, once notably hung an American flag on a John Hancock Center antenna in Chicago to celebrate the moon landing in 1969. He later switched to installing antennas atop skyscrapers, as if to keep life from getting boring. In the early 1980s, he returned to the John Hancock antenna to set up a grill on the roof and cook steaks for every member of his crew at $5 apiece. In 2018, at 80 years old and some 50 years since his adrenaline-filled lifestyle in the skyline began, Rukavina was still at it.

“It’s safer to be on that antenna,” Rukavina told the Chicago Tribune in 2018, “than it is to jaywalk on LaSalle Street at noon.”

Read Next: The Real-Life Outlaws Behind ‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’

Comments