If you want to find out if the milkman is your dad, Maury can help you out. If you’re trying to learn about all the branches of your family tree, there are a bunch of genealogy websites that will connect the dots you need connecting. But if you want to confirm your long-dead great-grandfather was Sitting Bull, you’re gonna need to do a bit more than go on a talk show or drop $100 on a website.

Apparently you need some hair, teeth, or bones and a motivated — and well-funded — research team. Scientists say they’ve shown, for the first time, it’s possible to prove genetic connections to long-dead individuals thanks to a new DNA tracing technique.

“In principle, you could investigate whoever you want — from outlaws like Jesse James to the Russian czar’s family, the Romanovs.“

A recent study published in Science Advances says researchers have figured out a way to determine familial relationships between people that have been dead for over 100 years and people who are still living or just recently deceased.

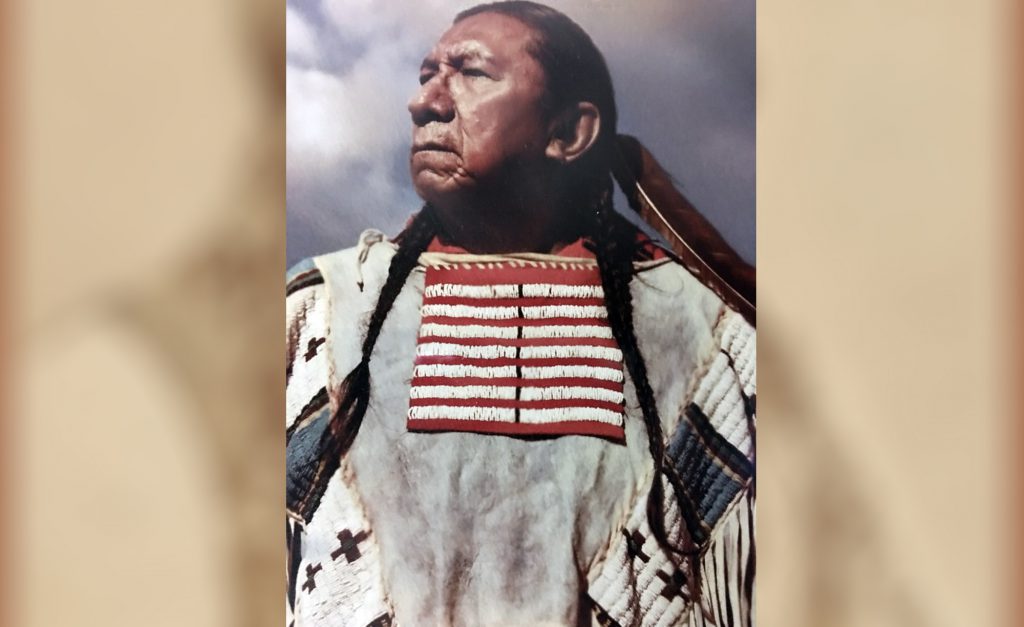

For 73-year-old Ernie LaPoint of South Dakota, that means he finally has science to back up what he always knew: that he and his siblings are descendants of Sitting Bull, the legendary chief and medicine man of the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux.

“Over the years, many people have tried to question the relationship that I and my sisters have to Sitting Bull,” he told Eureka Alert.

LaPoint had long-known that he was the great-grandson of Sitting Bull but could only prove it through birth and death certificates and historical records, which left room for doubt.

“It’s just another way of identifying the relationship to my ancestor,” LaPoint told The Washington Post. “With this, it’s a lot more definite. This is a scientific way of determining our lineage. You can’t break that lineage now. No one can come in and say it’s wrong.”

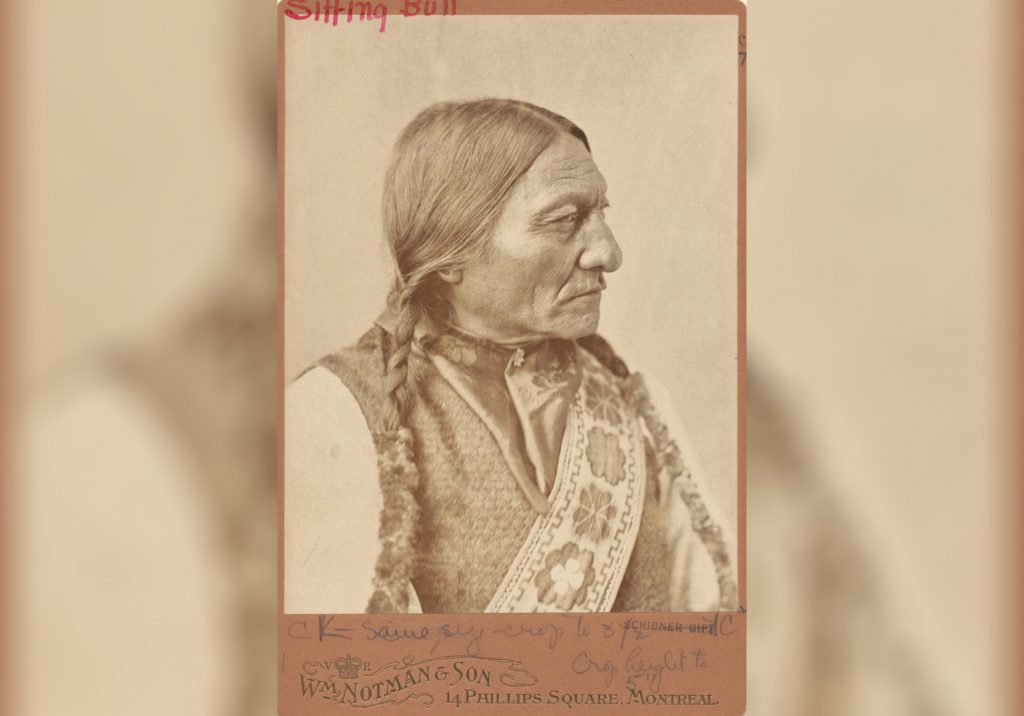

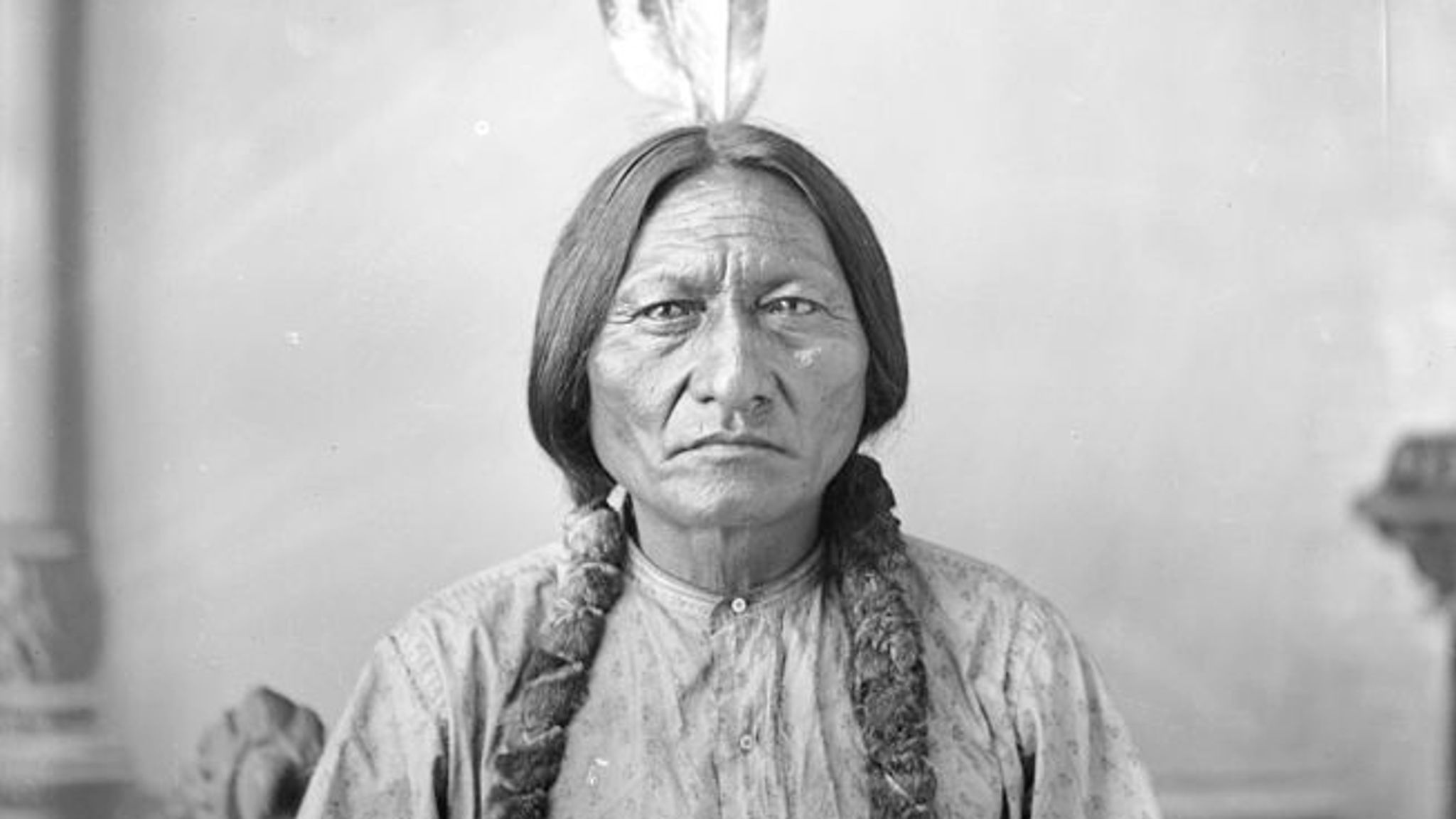

Born in 1831 as Tatanka Iyotake, Sitting Bull was best known for leading the Sioux resistance against the US government and settlers stripping them of their tribal lands.

Sitting Bull led the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes in the infamous 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn, wiping out Gen. George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry Regiment. The chief was killed in 1890 while being arrested on the Standing Rock Reservation.

Horace Deeble, an Army physician at Fort Yates in North Dakota, cut the braided scalp lock from Sitting Bull’s head and kept it. A scalp lock was a long lock of hair grown at the top of the head, a hairstyle worn by some Native American men. Deeble also took the wool leggings he was wearing.

The hair and leggings were later donated to the National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C. The museum returned the items to LaPointe and his three sisters in 2007.

Dr. Eske Willerslev, a Danish evolutionary geneticist who was one of the study’s authors, heard about Sitting Bull’s hair and leggings being repatriated and contacted LaPointe. He wanted to see if more could be done to examine the DNA still present in the hair using the new tracing technique.

Willerslev and his colleagues couldn’t have been happier with the results.

“We managed to locate sufficient amounts of autosomal DNA in Sitting Bull’s hair sample, and compare it to the DNA sample from Ernie Lapointe and other Lakota Sioux – and were delighted to find that it matched,” said Willerslev, who is a professor at Cambridge and head of the Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Centre at the University of Copenhagen.

The report states, “to our knowledge, this is the first published example of a familial relationship between contemporary and a historical individual that has been confirmed using such limited amounts of ancient DNA across such distant relatives.”

“In principle, you could investigate whoever you want — from outlaws like Jesse James to the Russian czar’s family, the Romanovs,” Willerslev said. “If there is access to old DNA, typically extracted from bones, hair or teeth, they can be examined in the same way.”

Read Next: John Wesley Powell and the 1869 Discovery of the Grand Canyon

Comments