Editor’s Note: Here at FRA, we are a small but aggressive team. We’re like a race car that we’re building while it zips around the track. Extending that analogy, Matt Smythe is the wheels: He is the primary point of contact between our edit team and our readers. When Matt joined FRA as a staff writer, he was an ad man, a poet, a fly fisherman, and a bowhunter. Soon, he added “daily content creator” to his resume as he became instrumental in crafting the voice of the FRA brand. All the while, he kept on writing poetry.

I always had a sneaking suspicion that poetry was simply a safe space for writers who were either too inept or too lazy to write prose. Matt says I’m full of shit, and I’m starting to think he may be right. I have the utmost respect for the trials and hurdles Matt has faced and overcome, and, to paraphrase Bukowski, I like how well he walks through the fire. Matt’s poetry is of the first order, which is why everyone at FRA is beyond excited about the publication of his first book. I still tell people I don’t like poetry much, except for the works of Matt Smythe and Dylan Thomas, in that order. — Michael R. Shea

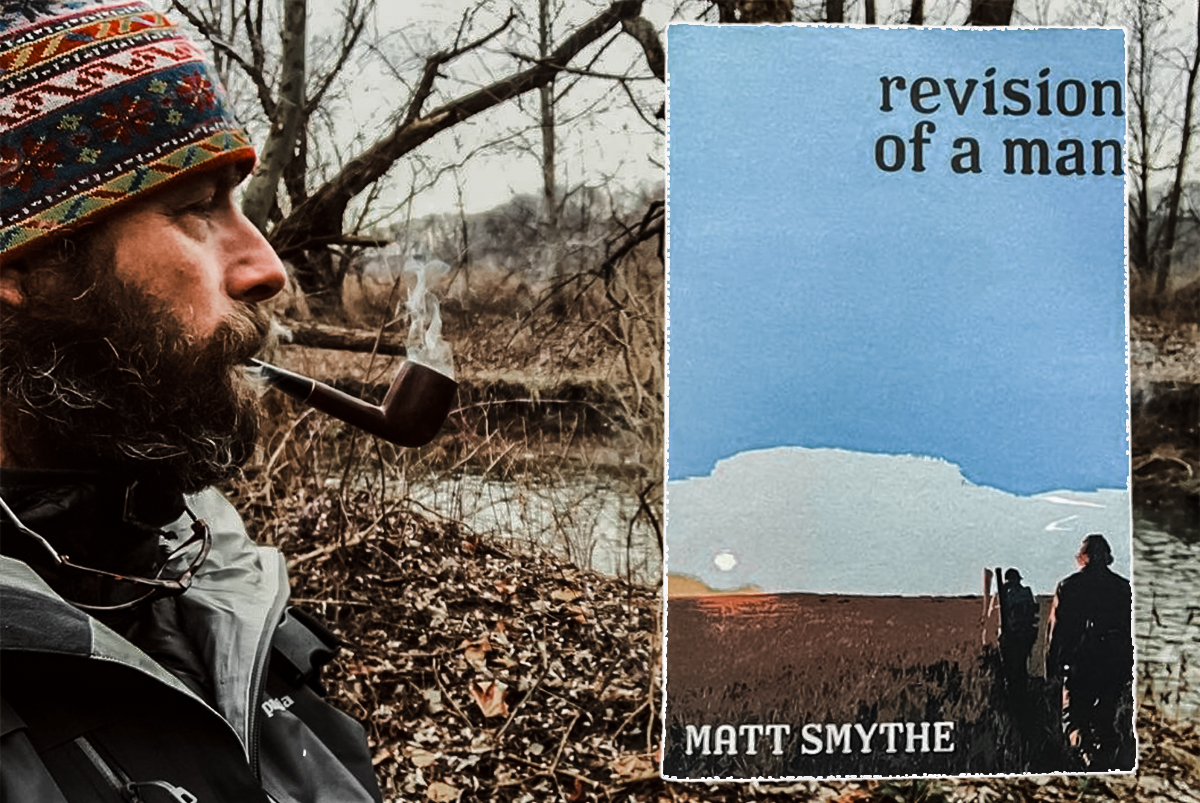

By traditional standards, Matt Smythe is as manly as they come. If he weren’t a dedicated father, he might live alone in a cabin in the woods or on a mountain. That doesn’t arise from disdain for other people but his insatiable desire to be constantly immersed in nature.

Smythe is a big-bearded Army veteran and an avid outdoorsman. He’s bagged some of North America’s most dangerous game, whose mounts now decorate the walls of his home. But intertwined with his myriad masculine attributes is a sensitive and thoughtful side.

When he’s not teaching his sons how to make their own fishing lures or working on his turquoise ’67 Bronco, Smythe is usually packing his pipe and putting his thoughts to paper. It’s at the intersection of these seemingly contradictory sides of Smythe’s personality that his upcoming collection of poetry was born. He’s written for a litany of outdoor magazines, but his first book — aptly titled Revision of a Man — tackles what it means to be a man in the modern age.

The collection begins with the haunting “Deal,” which weaves themes of parenthood, sobriety, and death into a story that sets the tone for Smythe’s dark and moody musings on masculinity. Following the appetizer, the book dives into its first section: Blood & Service.

It starts with an ode to the Finger Lakes region of New York, where Smythe was raised, then moves on to a short poem titled “Imprint” that captures the beginning of Smythe’s love for the woods and waters of his home.

“In me was a greedy curiosity for water, for the outdoors, / for the uncharted backwoods bird, animal, fish-filled places where I felt hidden.”

Smythe’s love for water flows into the next poem, “Cemetery Spring Run,” where he describes catching fish with his bare hands. His description of the unorthodox fishing method puts the reader into the mind of a child, nervously feeling along the dark stream bottom for a freshwater leviathan to grab.

The poems rush through the beginning of the first section like the water of Cemetery Spring Run, then crash into Smythe’s transition from boyhood to manhood. His initial idea of what it meant to be a man comes from a mixture of the Army and his father — a father who, at one point, advised Smythe that “if I ever had to fight that I should fight like my life depended on it—fight like the other guy had my death in mind.”

His father’s example of masculinity comes through the pages as gentle and nurturing but also violently protective.

“Dad took the tire-iron and the consciousness of one and part of the other’s nose—spat it like tobacco in the dust of the parking lot,” Smythe writes of his dad defending a drunk friend in “Three Ways of Looking at My Father.”

But it’s in the final poems of the collection, focused on his own turn at being a father, that Smythe’s understanding of manliness comes through as clear as the glacial water of a mountain stream. Moments of sharing his love of nature with his children reveal a man to be the sum of all of his life’s work. Smythe passes on the lessons he’s learned to his readers the same way he’s passed on the skills of an outdoorsman to his children.

Whether describing parking lot fistfights or the death of an Army Ranger in “The River Did Not Weep,” Smythe writes through the green lens of mother nature. The great outdoors shaped Smythe’s ideals of manliness even more than his family or his military service did. With beautiful tributes to the women in his life, to the blues, and of course, to the natural world that has dominated his life’s course, Smythe crafts something akin to A River Runs Through It in poetry form.

Revision of A Man by Matt Smythe, Dead Reckoning Collective, 98 pages.

This content was originally posted by Coffee or Die magazine in May 2022.

READ NEXT – Clint Emerson Teaches Readers to Live ‘the Rugged Life’ with New Book

Comments