When The Revenant came out in 2015, it made a big splash for a few reasons. The film’s star Leonardo DiCaprio earned a best actor Oscar for his depiction of a legendary mountain man: the real Hugh Glass. The bear-attack scene made headlines, too. But is it real? Did any of the gritty and heartbreaking violence really happen? Yes. And no. And yes.

When we meet Glass in the movie The Revenant, he is given a vague backstory, delivered via a few stylized flashbacks and voice-overs, that reveals he once lived with a Pawnee tribe with a wife and child. At some point, his wife was killed; Glass’ son is a teenager and now his hunting partner, both working as guides for a group of trappers in the Dakotas.

This kind of sets him apart from the rest of the men, and we get the feeling that he and his son are seen as hunters and guides, but not one of the group somehow. The real Hugh Glass had no such son and was likely not much different in terms of experience and temperament than many of the men in the group of trappers, though he might have been a bit older at the age of 39.

The Real Hugh Glass

Hugh Glass was born in 1783 in Pennsylvania to Scots-Irish parents, but his early life is a mystery and there’s no way to know which stories about Glass’ later life are true and which are fiction — as is common among mountain men of the era.

Glass had an eventful life before the events depicted in the movie. In 1816, he was reportedly captured off the coast of Texas by pirates commanded by Jean Lafitte and forced into piracy for two years. He purportedly escaped by swimming to shore near what is today Galveston, Texas.

He was also rumored to have been captured by the Pawnee at some point in his life and lived with them for several years — which is almost certainly where the filmmakers got the idea to create his fictional half-Pawnee son, Hawk.

In 1821, Glass ended up in St. Louis, Missouri, when he accompanied several Pawnee delegates to meet with US government authorities. The following year, Gen. William Henry Ashley put an ad in the Missouri Gazette and Public Advertiser. He wanted to amass a corps of 100 men to follow the Missouri River into the mountains on a fur-trading expedition. Among the men who answered the call were some famous names who would go on to become legendary mountain men, including Thomas Fitzpatrick, James Beckwourth, Jedediah Smith, and Jim Bridger. But, in 1822, they were all known as Ashley’s Hundred.

Glass joined the company about a year after it was formed and ascended the river with Ashley and other new recruits in June 1823 to meet up with the original group.

The group was soon after attacked by Arikara warriors, and Glass was shot in the leg, with bow or gun we do not know. The survivors then retreated downriver. This attack was likely the basis for the Ree attack depicted in the beginning of The Revenant.

A letter survives from Glass to the father of one of the men, John S. Gardner, who was killed in the attack on June 2 (below with spelling modernized):

Dr Sir:

My painful duty it is to tell you of the death of your son who befell at the hands of the Indians 2nd June in the early morning. He lived a little while after he was shot and asked me to inform you of his sad fate. We brought him to the ship when he soon died.

Mr. Smith a young man of our company made a powerful prayer who moved us all greatly and I am persuaded John died in peace. His body we buried with others near this camp and marked the grave with a log. His things we will send to you.

The savages are greatly treacherous. We traded with them as friends but after a great storm of rain and thunder they came at us before light and many were hurt. I myself was shot in the leg. Master Ashley is bound to stay in these parts till the traitors are rightly punished.

—Yr Obt Svt Hugh Glass

How the Famous Bear Attack Really Went Down

In the movie, the bear attack follows a fierce battle with the Ree that sends the group retreating to their boat, which they later abandon for fear that they will simply be attacked downriver by the same group. Beat up and lacking provisions, they begin to walk back to Fort Kiowa the long way while trying to evade their attackers. That’s when the bear attacks Glass.

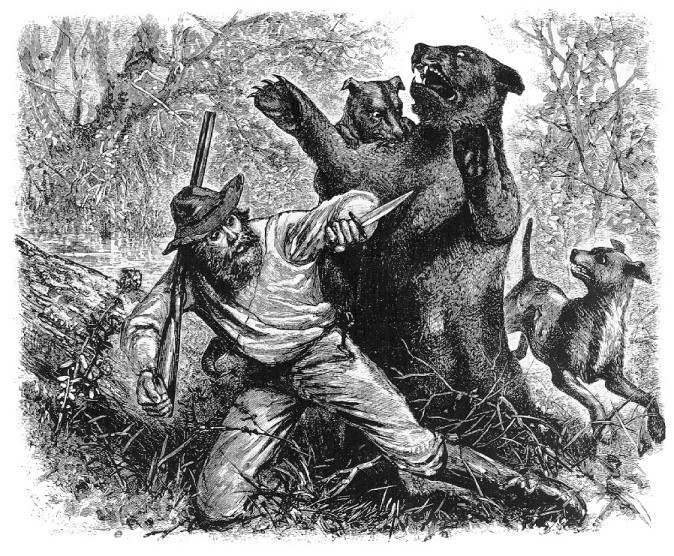

In reality, the attack wasn’t couched in so much drama. The Ashley party regrouped at Fort Kiowa for a trip west and picked up a few extra members. Glass and several others, including Ashley, set out for the Yellowstone River on a scouting mission. Glass was scouting for game for the expedition near the fork of the Grand River in South Dakota when he stumbled upon and surprised a grizzly bear with two cubs.

Glass was severely mauled but managed to kill the bear when the members of his party showed up to help. In the movie, Glass kills the bear by himself and his companions don’t show up until the attack is over.

Despite the fact that nobody thought Glass could survive, the men carried him for two days, but it slowed them down too much. Still convinced he’d die, Ashley asked for two men to stay with Glass until he finally did so, then bury him. The volunteers were John S. Fitzgerald, and a man only identified as “Bridges,” who may or may not have been Jim Bridger. Regardless, he was depicted as a young Jim Bridger in the movie.

The Revenant fills this bit of decision-making with a deep sense of urgency. The Ree are presumably right on the group’s tail, potentially so near that Fitzgerald is worried the shot Glass fired into the bear during the attack would draw them; they have no supplies, have lost all their furs, and have no idea how long it will take them to reach the fort on foot on this route; and now, their guide has been taken out by a bear.

Without all this manufactured tension and danger added for the film, the real-life decisions made by Glass’ comrades — to first leave two men behind to wait for him to die, and then for those men to leave him to die alone — take on a kind of pragmatic cruelty that broad modern audiences may not be able to fully understand, and likely wouldn’t condone at all.

Now getting to my biggest problem with the changes to the actual events, and it has to do with what the addition of Hawk does to the circumstances of Glass’ abandonment.

They Just Had To Hollywood It Up

The true story of Hugh Glass surviving a bear attack, being left for dead by the men who were supposed to stay with him, and then literally dragging his mangled ass through miles and miles of untamed wilderness to call out the men who did him wrong, is a hell of a story. But apparently, it’s just not enough for Hollywood, so they had to add a fictional son, who is, of course, murdered by one of the men who abandons Glass.

This offers up a stereotypical villain in John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy) and the emotional motivation the movie thinks Glass needs to perform his incredible feats of survival.

Fitzgerald obviously hates Glass and his son, as evidenced by the shit he says and the way he acts, yet nobody finds it suspicious that he volunteers to stay with Glass for some extra pay.

Glass’ fictional son stays with Fitzgerald and Bridger in the movie and catches Fitzgerald trying to suffocate his father. The boy screams for Bridger, who is off getting firewood and water, until Fitzgerald stabs him to death in front of Glass. When Bridger returns, he tells him he doesn’t know where Hawk is, and that night, Fitzgerald wakes Bridger with a lie, whispering that the Ree are upon them and that they have to leave in a hurry. They do so, leaving Glass behind, alone, partially buried, and still alive.

In real life, the men who stayed with Glass caught up to Ashley’s party and said Glass had died, and that they’d been interrupted burying him by the Arikara, who forced them to grab Glass’ gear, including his knife and rifle, and flee.

Here’s the problem with the film version:

After Fitzgerald kills the fictional Hawk, right in front of Glass, why doesn’t he also kill Glass before Bridger comes back? Hell, he tries to convince Glass to let him do it earlier and actually attempts to suffocate him.

The audience has to believe first that Bridger would believe that Hawk just ran off and disappeared, leaving his dying father with two strangers, one of whom he loathes completely, for no discernable reason. We also have to swallow that Bridger buys this for a whole day and night (Glass cannot tell him otherwise due to the wounds to his throat).

Then, we also have to believe that Fitzgerald, though he had no problem killing Glass in cold blood a moment ago before shoving a knife through Hawk’s liver, somehow has a crisis of conscience that prevents him from finishing Glass off. It doesn’t track.

It’s much more believable that two guys, left alone in the woods with a guy who is 90 percent dead, got antsy, but also didn’t want to murder the guy. So, they just left to let nature take its course.

The real story teaches the lesson, “Don’t take anything for granted, even death, because it will come back to bite you.” It’s also a dire warning against taking the easy way out.

The movie teaches, “Don’t be a murdering coward, because some guy might kill you to avenge his son one day.”

Going Hollywood with the ending missed a huge opportunity to say something meaningful, something real.

The filmmakers also required Glass’ journey to be made more symbolic and difficult. Isn’t a guy being really pissed about being left for dead and willing himself to survive enough? It sure makes more sense.

The movie also adds a random loner Pawnee who essentially saves Glass’ life, feeds him, cleans his wounds, and shelters him through a storm. It makes Glass less badass than he really was. I’m not even mentioning the most outlandish part where he rides a horse off a cliff and then falls through the branches of a gigantic pine tree, reaching the forest floor below unharmed, and then proceeds to cut open said horse and use it as shelter during a blizzard. The gutting scene looked real, but c’mon.

He gets the horse that will become his shelter when he rescues the aforementioned random Pawnee’s daughter, whom he just happens upon during his journey, being held captive by a group of white rapists.

Mauling Injuries

The movie really made an effort to get Glass’ injuries right. He had numerous festering wounds, a broken leg, and lacerations on his back deep enough to expose his rib bones. That’s pretty much what we see in the movie, with a good throat wound thrown in to prevent Glass from talking — because plot, and so we could get a scene of Glass cauterizing his own throat with gunpowder.

The real Glass set his own leg, used maggots to clean his wounds, and wrapped himself in the hide of the bear that had mauled him, which was intended to be his death shroud, before tackling the 200 miles back to Fort Kiowa on his hands and knees.

He eventually made it to the Cheyenne River, where he built a crude raft and floated downstream to Fort Kiowa, surviving on a diet of berries and wild roots. It took him six weeks.

Some might say that a guy just battling nature and a bear mauling isn’t eventful enough for a whole movie, and I would say, perhaps the movie doesn’t have to be two and a half hours long.

The Real-Life Ending

The flavor of Glass’ vengeance lust is even ratcheted up for the movie. In The Revenant, Glass gets back to Fort Kiowa to find that Fitzgerald has fled after robbing Ashley’s safe. Ashley confronts Bridger, but Glass calls him off, saying his abandonment wasn’t his fault. Then, before even bothering to fully heal, Glass sets off to track Fitzgerald down and kill him for murdering his son.

Glass tracks Fitzgerald down, and after a bloody hand-to-hand fight in the snow, Glass leaves the killing to the Ree, who are conveniently present to finish Fitzgerald’s scalping. And that is where the movie leaves Hugh Glass.

IRL, Glass healed up at Fort Kiowa a bit before traveling to Fort Henry with a group of traders upriver looking for “Bridges.” As part of Ashley’s group, Glass was able to buy a rifle, shot, and powder on credit. He left the group of traders at a sharp bend in the river, opting to travel overland to the village trading post destination near the fort. It’s fortunate he did. The boat was soon attacked by the Arikara and every man was killed. Glass himself was set upon by Arikara warriors on his way to the village but was rescued by two Mandan men who took him to the trading post where he learned of his traveling companions’ fate.

At this point, all told, Glass had been mauled by a grizzly, left to die, and involved in three attacks by Native Americans that claimed the lives of 21 men and wounded 16 others.

After a 38-day walk, Glass found Fort Henry deserted and a note (allegedly) saying the company had moved to a new camp at the mouth of the Bighorn River due to poor trapping and constant harassment by the Blackfeet. When Glass arrived there, he did indeed find Bridges, one of the men who abandoned him, but reportedly forgave him because of his youth and because he determined Fitzgerald was the driving force behind his abandonment.

Then, Glass survived another adventure that left him alone in the wilderness after an Arikara attack, having to again survive off the land and make his way back to Fort Kiowa on foot, but this time, a bear hadn’t torn him to shreds and he still had his knife and flint.

After that, Glass finally caught up with Fitzgerald at Fort Atkinson in present-day Nebraska and discovered the other man who had abandoned him and stolen his rifle had joined the Army.

Glass was forced to abandon his revenge plans after talking with Fitzgerald’s captain, who warned him that if he went through with killing the man, he’d be hanged for killing a soldier of the US Army.

Fitzgerald’s captain forced him to give Glass back the rifle he’d stolen when he left him for dead. Glass responded by telling Fitzgerald he better stay in the Army, because if he ever left, he’d kill him.

Glass returned to his life as a trapper and fur trader on the frontier and later worked for the US Army garrison at Fort Union near Williston, North Dakota, as a hunter.

In 1833, Glass was killed along with two other trappers when they were attacked by the Arikara on the banks of the Yellowstone River.

Today, a monument to Glass stands on the reported site of his mauling on the southern shore of the present-day Shadehill Reservoir in Perkins County, South Dakota. Nearby, you will find the Hugh Glass Lakeside Use Area, a state-managed campground.

Comments