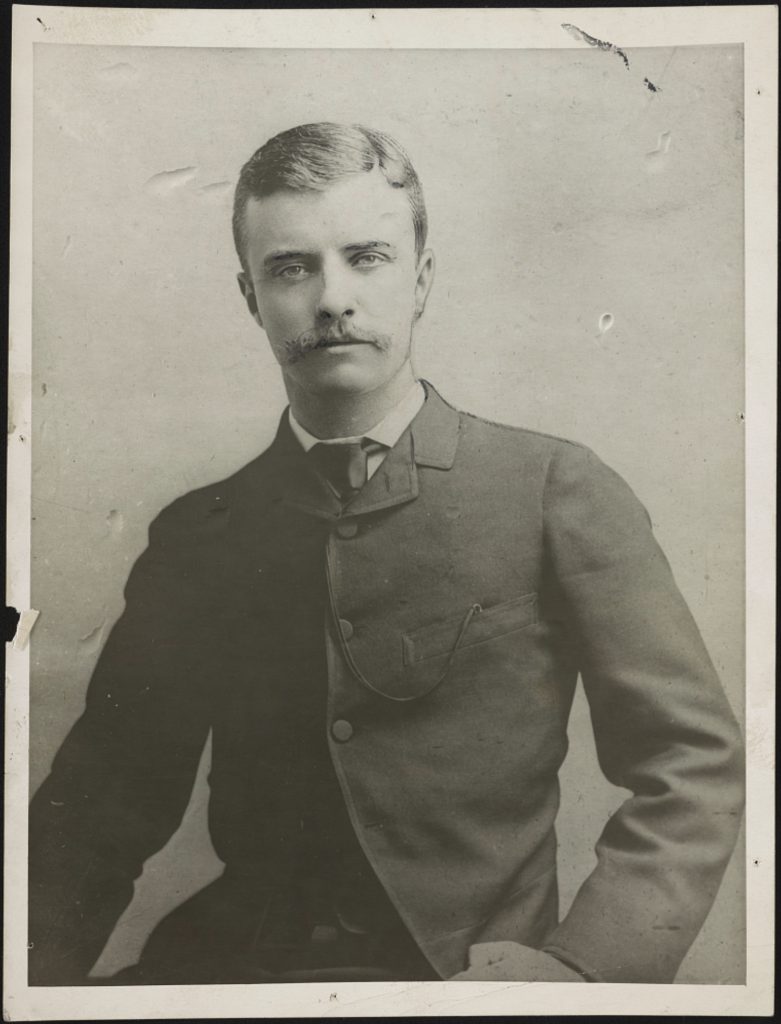

On Sept. 7, 1883, Theodore Roosevelt, an up-and-coming politician with pronounced eyeglasses and a gregarious personality, stepped off a Northern Pacific Railway train headed westward to the Little Missouri settlement of the Dakota Territory.

Eager to experience the thrills of the Wild West before they presumably vanished, the adventurous New Yorker embarked on a once-in-a-lifetime cross-country journey to snag a prized buffalo and enjoy some of the best antelope, deer, and elk hunting known at that time.

This young man’s excursion would be life-changing for him — and would ultimately transform the path of an entire nation.

Roosevelt would later state with an affirmation to the American people: “I have always said I would have not been President had it not been for my experience in North Dakota.”

Roosevelt the Hunter

Trekking into the Wild West was once considered a daunting proposition in the early half of our nation’s history. After decades of conflict across the Great Plains between Native American tribes and the US military and the rise of the American railroad, the lands west of the Mississippi River became a hotbed destination for settlers, prospectors, investors, and dreamers who pursued their own version of the American Dream.

Roosevelt was no different, as he’d developed a keen interest in frontier life at a very young age. He was dazzled by tales of the Wild West and was enamored with the idea of experiencing frontier life before his chance would disappear. Alas, one major obstacle stood in his way — his health.

As a child and throughout his youth, Roosevelt suffered from severe asthma, which inhibited him enough that doctors worried about his long-term prognosis. But that didn’t stop him from falling in love with the outdoors and becoming an adventurer and hunter in his youth. To counter his asthma, Roosevelt believed he needed to embrace a strenuous lifestyle, an idea that would be part of his persona and a philosophy in his political life.

At the age of 24, Roosevelt’s pursuit of a strenuous life would hit full throttle. Stepping off that late September train from a break in his duties in the New York State Assembly, he had made it to the Dakota Territory to embark on his bison quest. On his first night in Little Missouri, he booked a cot at the Pyramid Park Hotel and waited until morning to begin his adventure. But he didn’t know a soul and didn’t have a guide for the hunt.

Despite being a chatterbox known to get his way, Roosevelt’s first advances in search of a hunting guide fell short. Much to his chagrin, the locals had an inherent distrust of most Easterners, let alone a politician, and scoffed at the idea that someone of his status could hack it out West. But Roosevelt wasn’t one to ever give up, and after hours of searching, he secured the help of Joe Ferris, a Canadian from New Brunswick, who was one of the first settlers in the region and spent time as a railroad worker at a nearby US Army cantonment. Ferris also was an avid hunter and knew the lands well that Roosevelt envied.

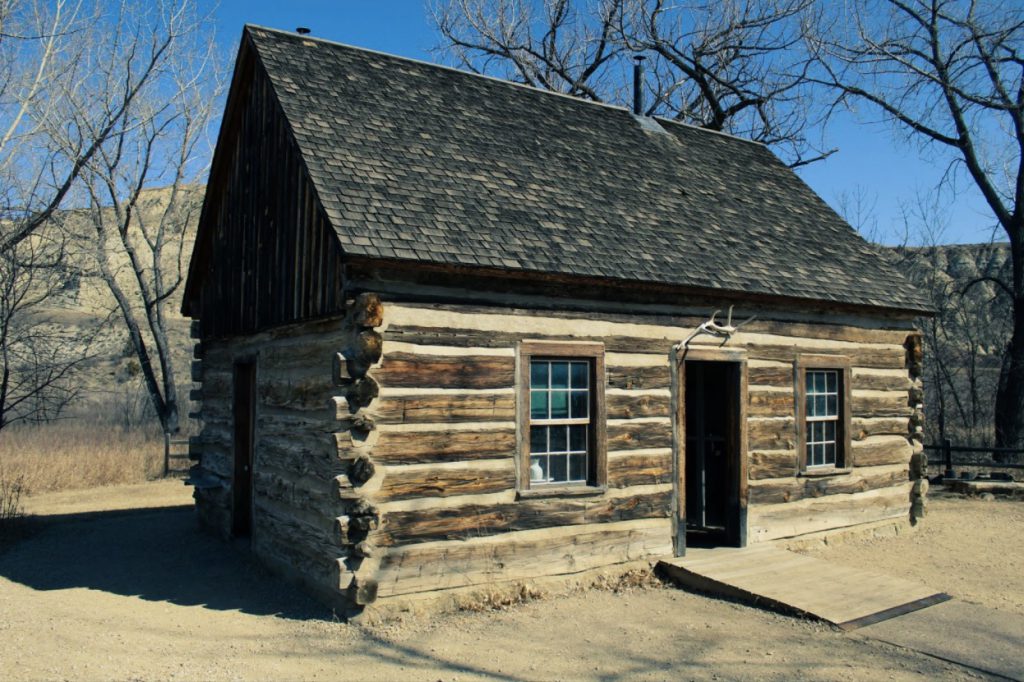

Later that day, the two went off on a lengthy horseback adventure and traveled the Little Missouri River to meet up with Joe’s brother, Sylvane, and a good friend and Canadian, Bill Merrifield, at the Maltese Cross Cabin. After a good night’s rest, the party of four trekked south another 50 miles and met up with Gregor Lang, whose ranch would become the base station of their hunting expedition — a voyage that would turn out to be much harder than any of them, especially young Teddy, would have imagined.

Roosevelt and his companions endured never-ending rainfall that made tracking their prey extremely difficult. Down on their luck and low in morale, all hope seemed lost until they finally came across a set of identifiable prints in the ground.

It was a make-or-break opportunity for the crew — the ultimate hell-or-high-water moment. After a miles-long trek in a storm that led them to Little Cannonball Creek in Montana, Roosevelt finally gazed upon the horizon and saw a buffalo on a ridge. He fired three shots in the pouring rain, but he wasn’t sure if he had hit the beast. As he approached, he could barely contain himself when he found his target dead on the ground. Roosevelt’s prized buffalo had been acquired, and he had an incredible story to tell everyone back home.

However, the palpable enthusiasm Roosevelt had after his first buffalo hunt would dwindle during future excursions. In 1889, he would snag his second buffalo, but he felt significant remorse as he became aware of the species’ eradication. Roosevelt would reflect on that day with ambiguous feelings.

“Mixed with the eager excitement of the hunter was a certain half-melancholy feeling as I gazed on these bison, themselves part of the last remnant of a doomed and nearly vanished race. Few indeed are the men who now have or evermore shall have, the chance of seeing the mightiest of American beasts, in all his wild vigor, surrounded by the tremendous desolation of his far-off mountain home.”

That moment proved to be a turning point in Roosevelt’s life, and it gave birth to his strong wildlife conservation beliefs, which would later turn into hallmark legislation that became a cornerstone of his presidency. In his two terms, he would wield unprecedented political power to preserve and protect the nation’s landscapes and the wildlife that existed on them.

Roosevelt’s actions would set aside more than 230 million acres of public land for conservation and codified development of the US Forest Service (USFS), America’s first 150 national forests, and five national parks as well as various bird and wildlife refuges.

Roosevelt’s reverence for the buffalo ran so deep that he became the honorary president of the American Bison Society (ABS), formed in his home state of New York at the Bronx Zoo in New York City in 1905. Together, Roosevelt and ABS formulated multiple buffalo reintroduction efforts still in force today to restore the population. Once on the verge of extinction, hundreds of thousands now roam our nation.

Without question, Roosevelt’s efforts to protect and preserve the beauty of our natural resources and environment were nothing short of historic. However, more experience in the Badlands, particularly his time as a rancher, also gave rise to other significant policies that would have an indelible impact on our nation.

Roosevelt the Rancher

In the days following his first buffalo hunt back at Lang’s ranch, he and his hunting partners would bask in the success of their hunt and pontificate about life, culture, and politics. But one topic interested Roosevelt more than anything — cattle ranching.

Cattle ranching wasn’t common in the early years of the Dakota Territory due to the buffalo’s abundance as the herd animal of choice. But when the buffalo population vanquished, a new opportunity arose, and cattle-ranching exploded during the Dakota Boom.

During the 1880s, more than 300,000 head of cattle migrated to the region, with most coming from Texas. Others came from railroaders, Civil War veterans, and farmers who purchased as much as they could afford and headed west in pursuit of their own American Dream. No matter who you were or where you came from, the Dakota Territory had a captivating allure that intrigued many, especially Teddy Roosevelt.

By the end of the trip, Roosevelt had fallen in love with the area. He had become so enamored with the cowboy and ranching culture that he agreed to purchase the Maltese Cross Ranch for $14,000 — nearly $380,000 in today’s value. He would hire Sylvane Ferris and Bill Merrifield as managers at the ranch, and they would take care of all operations as Roosevelt made his way back to New York for his next duties in the State Assembly. Roosevelt promised to return when he could.

But Roosevelt’s plans changed drastically in the blink of an eye. Less than half a year after returning to New York, he endured profound tragedy when he lost both his wife and mother on Valentine’s Day in 1884. He would inscribe a big X into his journal for that day, and beside it he wrote, “The light has gone out of my life.”

To bring light back in his life, Roosevelt traveled back to his Maltese Cross Ranch after the 1884 Republican Convention. Over the next several years, Roosevelt’s western experience would revive and give new meaning to his life.

“Roosevelt came out west to heal. To this day, I believe there are still people coming to the west to seek the life of the cowboy and rancher for that purpose,” said Joe Wiegand, known nationally for his reprisal efforts and knowledge of Roosevelt, who also serves as the major gifts officer for the Theodore Roosevelt Medora Foundation. “It puts you in touch with the good soil, the animals, the hunting, and all of creation. Things central to the fabric of these lands and the rancher and cowboy ethos.”

Teddy found refuge in the Badlands, and shortly thereafter he developed Elkhorn Ranch, which would become his primary homestead. He employed Bill Sewall and Wilmot Dow as ranch managers, who were longtime friends that had been hunting guides for Roosevelt on trips to Maine in his youth.

“Roosevelt was our first cowboy president. A man equally of the west and of the east, especially the latter by birth, upbringing, and heritage. Yet, his western experience was real. The work that he did as a rancher was real. He wasn’t just an owner and investor. He was there right amongst his men,” Wiegand said.

“He worked the roundup and the trail, although he would admit he wasn’t a great roper. There are endless stories of him spending 24 consecutive hours being in the saddle and many other cowboy vignettes that define his time here.”

On top of his ranching duties, Roosevelt also made a significant effort to help establish law and order in the West. In 1885 and 1886, he served as a deputy sheriff for Billings County. He became a beacon of hope for his fellow ranchers and cowboys who were often the targets of cattle rustling and property theft. Roosevelt had a deep moral conviction and believed it was his civic duty to make the West civilized for everyone.

In April 1886, Roosevelt would experience such woes firsthand when three thieves stole his boat on the Little Missouri River on his Elkhorn Ranch property. What ensued was a weeklong manhunt and an 80-mile journey that would result in Roosevelt, Sewall, and Dow capturing the thieves and taking them to Dickinson, North Dakota, to be tried and sentenced.

Raucous outlaws and lawlessness weren’t the only outside factors Roosevelt and his fellow ranchers had to worry about. They always had to be cognizant of the weather.

The summer of 1886 proved to be one of the worst in history. The land scorched with soaring heat that brought unprecedented wildfires and drought. Herd numbers were at an all time high, and there wasn’t enough open range grazing to keep them fed for the winter. The winter of 1886-1887, dubbed the The Big Die-Up, would result in nearly 80 percent of cattle being killed in the region.

When Roosevelt returned to Elkhorn Ranch in March 1887, his worst fears had been realized. More than half of his herd was dead, a devastating blow to the profitability of his cattle operations. He sold off most of his interests and went back to New York to advance his career in politics and writing.

Though Roosevelt’s cattle endeavors came to an abrupt end, the rancher and cowboy ethos would remain with him forever, and it would serve as the inspiration for the Rough Riders, the cavalry unit in which he served as lieutenant colonel during the Spanish-American War.

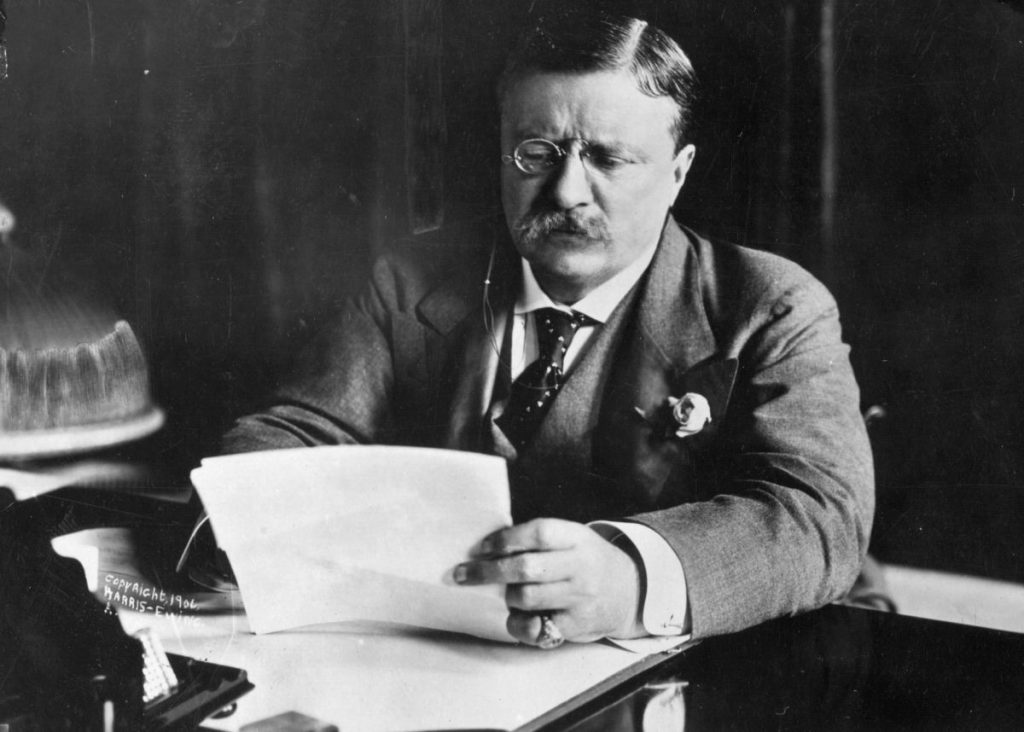

And perhaps most importantly, it led to Roosevelt becoming the preeminent voice for cattlemen and ranchers nationwide and helped propel him to the presidency in 1901.

Roosevelt saw firsthand how powerful corporations had become with the rise of the railroad industry. To protect farming and ranching interests, as well as basic rights for ordinary individuals, he would champion his Square Deal policies, which would become another hallmark of his presidency.

“All I ask is a square deal for every man. Give him a fair chance. Do not let him wrong any one, and do not let him be wronged,” he would say.

That’s how Roosevelt succinctly defined his vision. The basic tenets were simple: conservationism, consumer protection, and corporate regulation.

While big businesses and politicians were often given rebates and reduced rates in exchange for services provided by the railroad, common folk were exempt from such privilege. Whether it was shipping off cattle or small-business owners trying to secure essential products, they were often subject to significant rate increases, which were neither fair or affordable and drastically hurt their well-being and profitability.

To remedy this issue, Roosevelt sought approval from Congress to pass the Elkins Act and the Hepburn Act. The two pieces of legislation forbid the railroad conglomerates from engaging in such predatory practices and led to further regulation that would be more beneficial for common people.

The passage of such legislation and other subsequent policies supported by Roosevelt had broken a long-standing precedent set by former presidents, who had allowed corporations to run things as they saw fit. However, he believed wholeheartedly that he had a moral responsibility to ensure a fair shake for all individuals in their personal and entrepreneurial pursuits.

“And that’s part of the cowboy ethos from the West that inspired Roosevelt coming into play. Roosevelt brought his cattle into the Chateau de Mores (owned by Marquis de Mores) to the slaughterhouse to sell,” Wiegand said.

“The previous night they had agreed on a price. But when the market changed in Chicago the next day, de Mores said he had to offer him half a cent less. Roosevelt disagreed and expected him to honor the agreement. When he didn’t, Roosevelt said, ‘Boys, get the cattle out of the pens and take them back to the range.’ That’s the square deal. It was all about fairness and living up to your commitments.”

Most certainly, Roosevelt’s experiences in the West were so transformative and life-altering that they inspired and forged him into one of the greatest presidents in American history.

Roosevelt would later reflect on his time in the West and pay homage to it in his autobiography by writing, “I do not believe there was ever any life more attractive to a vigorous young fellow than life on a cattle ranch in those days. It was a fine, healthy life, too; it taught a man self-reliance, hardihood, and the value of instance decision — in short, the virtues that ought to come from life in the open country.”

Read Next: Back From the Brink: The Fall and Rise of the American Bison

Comments