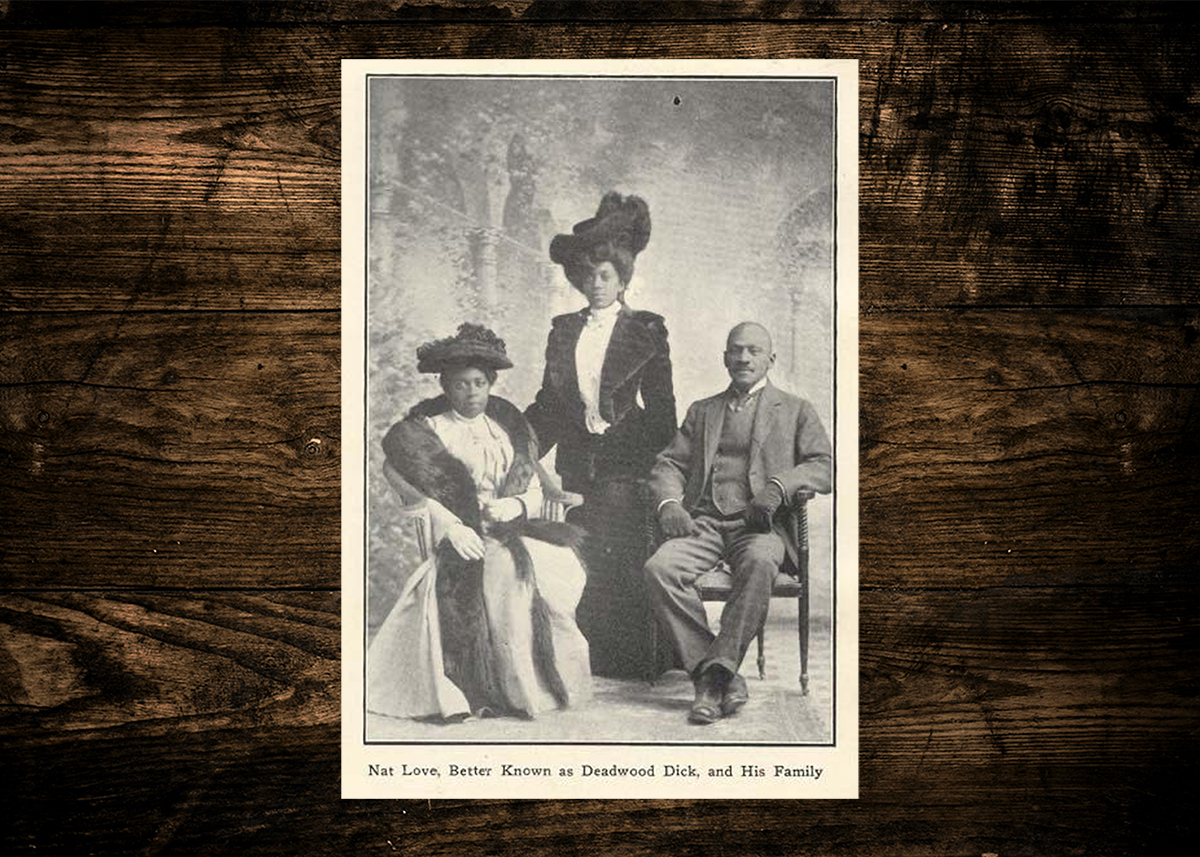

If Nat Love hadn’t learned how to read and write, then we’d never know one of the greatest Black heroes of the American frontier. We wouldn’t have learned his firsthand account of life growing up as a slave. We wouldn’t have the perspective of one of the only Black cowboys to write of his adventures across the Old West. We wouldn’t know how he tried to rope one of Uncle Sam’s artillery cannons and ride away with it, or how legendary lawman Bat Masterson didn’t arrest him because Love told him he wanted to bring the cannon back to Texas to fight the Indians with it.

“In an old log cabin, on my Master’s plantation in Davidson County in Tennessee in June, 1854, I first saw the light of day,” Nat Love wrote in his autobiography The Life and Adventures of Nat Love. “The exact date of my birth I never knew, because in those days no count was kept of such trivial matters as the birth of a slave baby.”

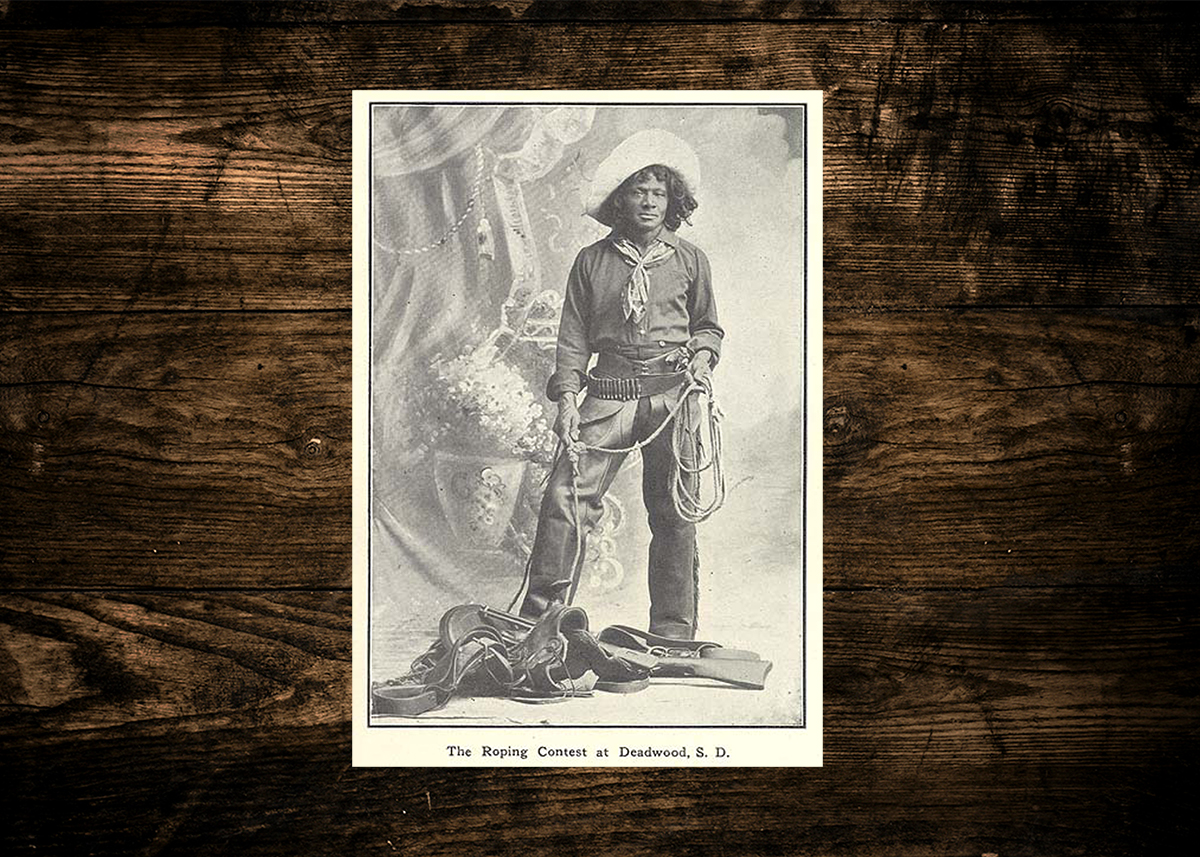

When he was around 15, a gambler came through town with a wild horse he raffled at 50 cents a ticket. Each Sunday while his slave owners went to church, Love took advantage of opportunities for mischief in the barn and discovered he had a gift for breaking horses. He sold chickens for a chance to win the wild horse, and when he won, he broke it and sold it back to the gambler for almost $100 — a hefty sum for anyone, let alone a newly freed slave.

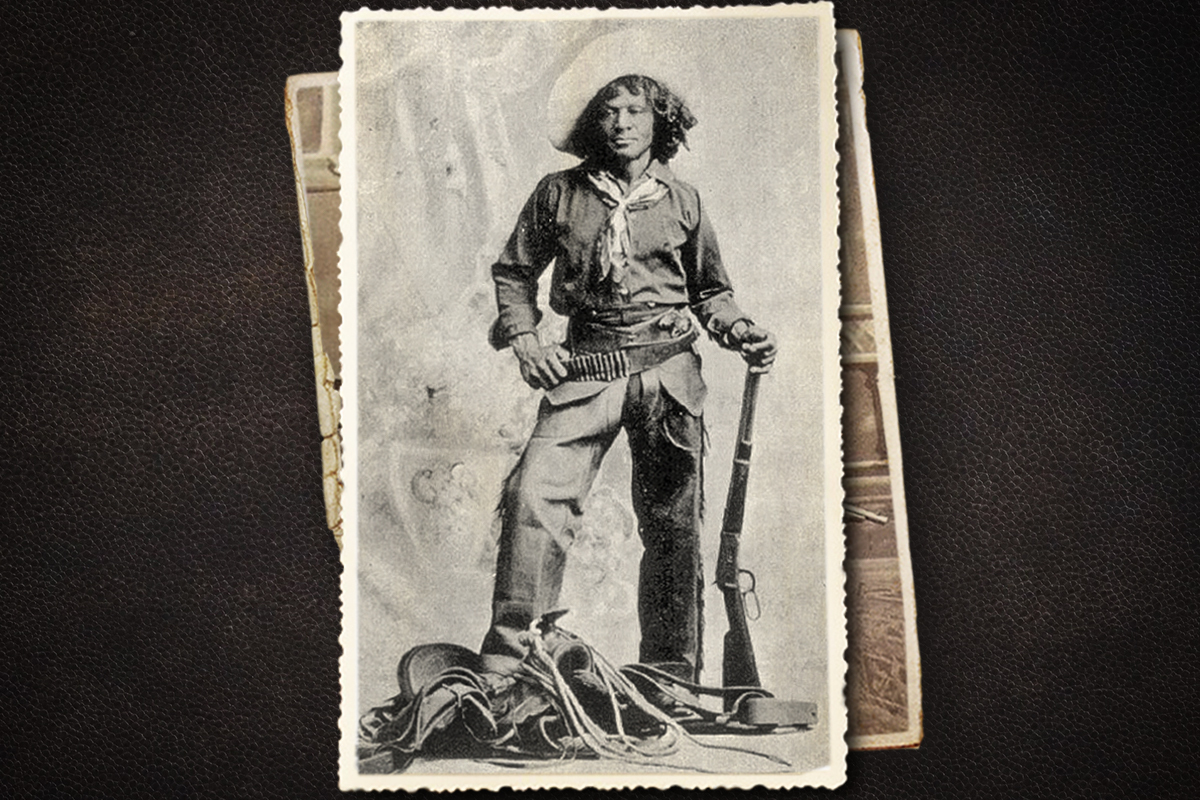

Love took his winnings to Nashville, then to Kansas where he took up with a group of cowboys from Texas. Once he proved his skill with horses, they hired him as a ranch hand and nicknamed him Red River Dick, for reasons we can only guess. Since he didn’t have a gun, his boss spun a six-cylinder Colt .45 revolver shut, handed it to him, and gave him a set of spurs, a saddle, and other essential gear to cowboy out of Dodge City.

“Now I had just got my outfit and had never shot off a gun in my life, but their words brought me back to earth and seeing they were all using their guns in a way that showed they were used to it, I unlimbered my artillery and after the first shot I lost all fear and fought like a veteran,” he wrote.

Love roamed with the cowboys all over Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. They escorted 500 cattle or more in a push. They rode through some of the harshest rain and hailstorms, with hailstones as large as walnuts and rain in heavy torrents. The cowboys hunted strays and roped them back into the herd, killed buffalo for food, and captured and broke wild mustangs.

“It was no trouble to get all the buffalo meat we wanted in those days, all that was necessary was to ride out on the prairie and knock them over with a bullet, a feat that any cowboy can accomplish without useless waste of ammunition, and a running buffalo furnishes perhaps the best kind of moving target for practice shooting,” Love wrote. “And the man who drops his buffalo at two hundred yards the first shot can hit pretty much anything he shoots at.”

On Oct. 4, 1876, in Yellow Horse Canyon, Texas, Love was ambushed by a group of Native Americans, shot twice through the leg and once in the chest. The braves, who Love later describes as belonging to Chief Yellow Dog’s tribe, caught him riding alone.

Love lay wounded on the ground, using his dead horse as cover, and held them off until his gun ran out of ammunition. He fought hand-to-hand combat, his nose was nearly scraped off his face, and one of his fingers was severed before he was subdued. But Yellow Dog’s tribe nursed him back to health, and curiously adopted him as one of their own. They named him Buffalo Papoose.

“I learned from them that I had killed five and wounded three while they were chasing me and in the subsequent fight with my empty gun,” he wrote. Love speculated in his book that the tribe, which was composed largely of “half breeds,” spared his life because his fighting prowess could be more useful to them if they could convert him. But Love wasn’t about all that. One night, he stole a pony and rode 100 miles in 12 hours without a saddle back to his ranch, and into the history books.

His stories were published in 1907 as action-adventure yarns for boys and men.

In one tale, he wrote about a vivid encounter with legendary lawman Bat Masterson. He had the liquid courage to attempt to raid a soldiers’ camp, rope a cannon, and ride home with it to use against the Native American tribes in Texas — or so he drunkenly thought.

A cavalry unit pursued him and he was arrested with the stolen fieldpiece. When Masterson arrived to hear his story from the jail cell, Love told him what had happened and they had a good laugh. His only crime in Masterson’s eyes was he drank too much whiskey, and he had to pay the tab for the night’s festivities. It came to $15. In the end, Masterson covered that, too.

“Laws have been enacted in New Mexico and Arizona which forbid all the old-time sports and the cowboy is almost a being of the past,” Love wrote in his final chapter. “But, I, Nat Love, now in my 54th year, hale hearty and happy, will ever cherish a fond and loving feeling for the old days on the range, its exciting adventures, good horses, good and bad men, long venturesome rides, Indian fights and last and foremost the friends I have made and the friends I have gained.”

Read Next: John Wesley Powell’s Geographic Expedition of 1869: The Discovery of the Grand Canyon

Comments