Most sportsmen who travel to Montana head almost immediately for its wilds to fish and hunt. On this trip to Big Sky Country, the mission is whitetails — chronic wasting disease–infected “zombie deer” specifically, but our first stop is a veterinary lab, not the field.

Yes, the term “zombie deer” is a bit overly dramatic, but it’s not an entirely inaccurate description.

Arriving in southwest Montana after cross-country dawn-patrol flights, my buddy and I stuff our bags in the back of the rental car and pull up directions to the Montana Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (MVDL) in Bozeman.

We’re here to get a firsthand look at how state wildlife officials and scientists are managing the highly transmissible and 100% fatal disease, as well as the testing process that determines which animals are infected and which are not.

For the second year in a row, the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks (FWP) has opened a managed hunting season for whitetail in Region 3, located in the southwest part of the state. The season runs from Dec. 11, 2021, to Feb. 15, 2022, and is meant to help cut the booming population of whitetails and slow the spread of CWD in the region.

I have three Montana whitetail tags that are good for bucks or does during the management hunt, a connection in the Ruby River Valley, and a new rifle that hasn’t yet drawn blood.

But first, we have an appointment with the head of MVDL to get into the weeds about CWD.

RELATED – Montana Deer Season Extended to Combat CWD, Booming Population

What is Chronic Wasting Disease?

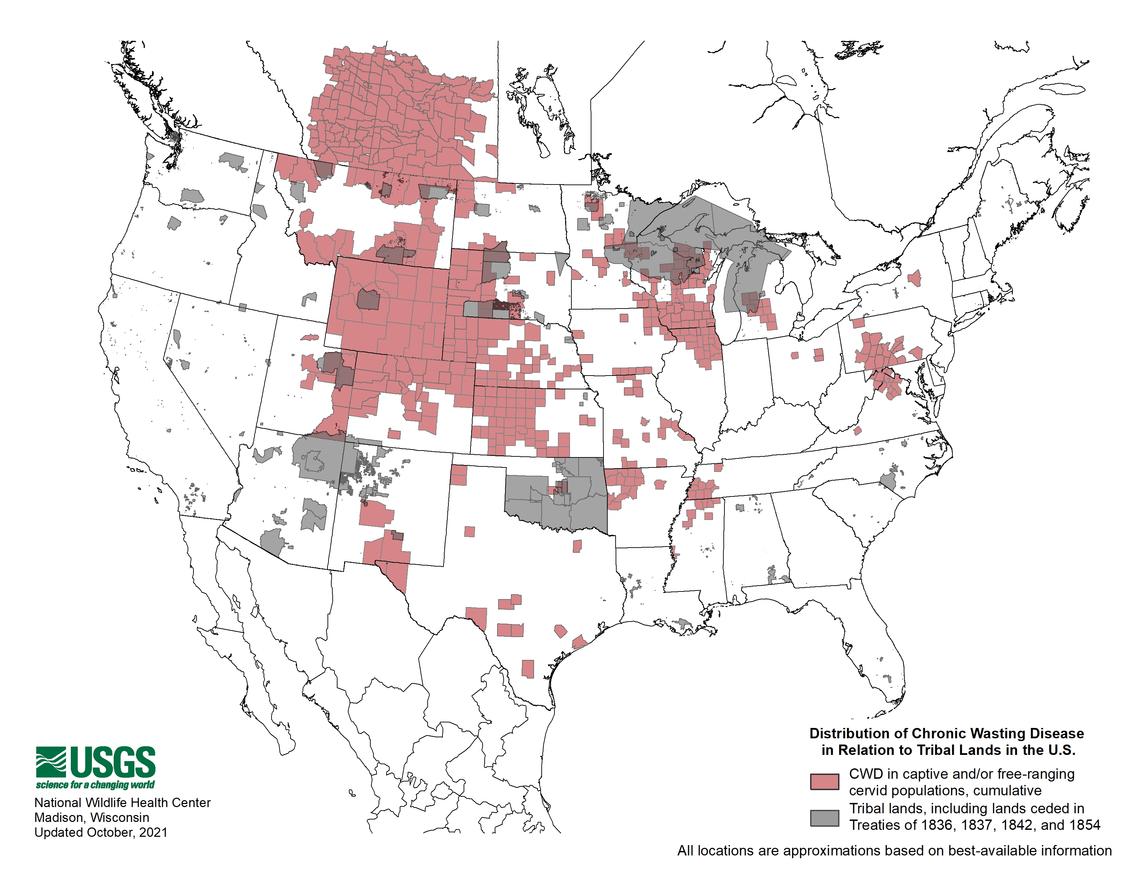

Most hunters west of the Mississippi have heard of CWD. East of the Big Muddy, there are pockets of awareness. However, even those who have heard of the disease only understand a small part of the big picture and the potential devastation CWD could wreak on deer populations across the country.

CWD is a neurodegenerative disease in ungulates (hoofed animals, including whitetail and mule deer, elk, moose, and caribou) caused by prion proteins. The prion is a folded protein that triggers normal versions of the same protein in the brain to fold abnormally.

The abnormal folding of the prion proteins leads to brain damage, drastic weight loss (wasting), stumbling, and listlessness. While symptoms of CWD may not be visible for up to two years in an animal, even if you could tell, there is no immunization against the disease. It is 100% fatal.

CWD is in the same family of prion diseases as Mad Cow Disease in animals and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in humans. There have been no cases of humans contracting CWD from deer.

So far, research has not been able to identify the molecular origin of the faulty protein.

Biologists do know that CWD is not a genetic disorder. It’s transmitted through physical contact via bodily fluids such as urine, feces, blood, saliva, as well as antler velvet and carcasses. The prion can be destroyed only by extreme heat or with bleach, so it will survive on anything it comes into contact with — plants, dirt, water sources. The prion even survives ingestion by animals other than deer.

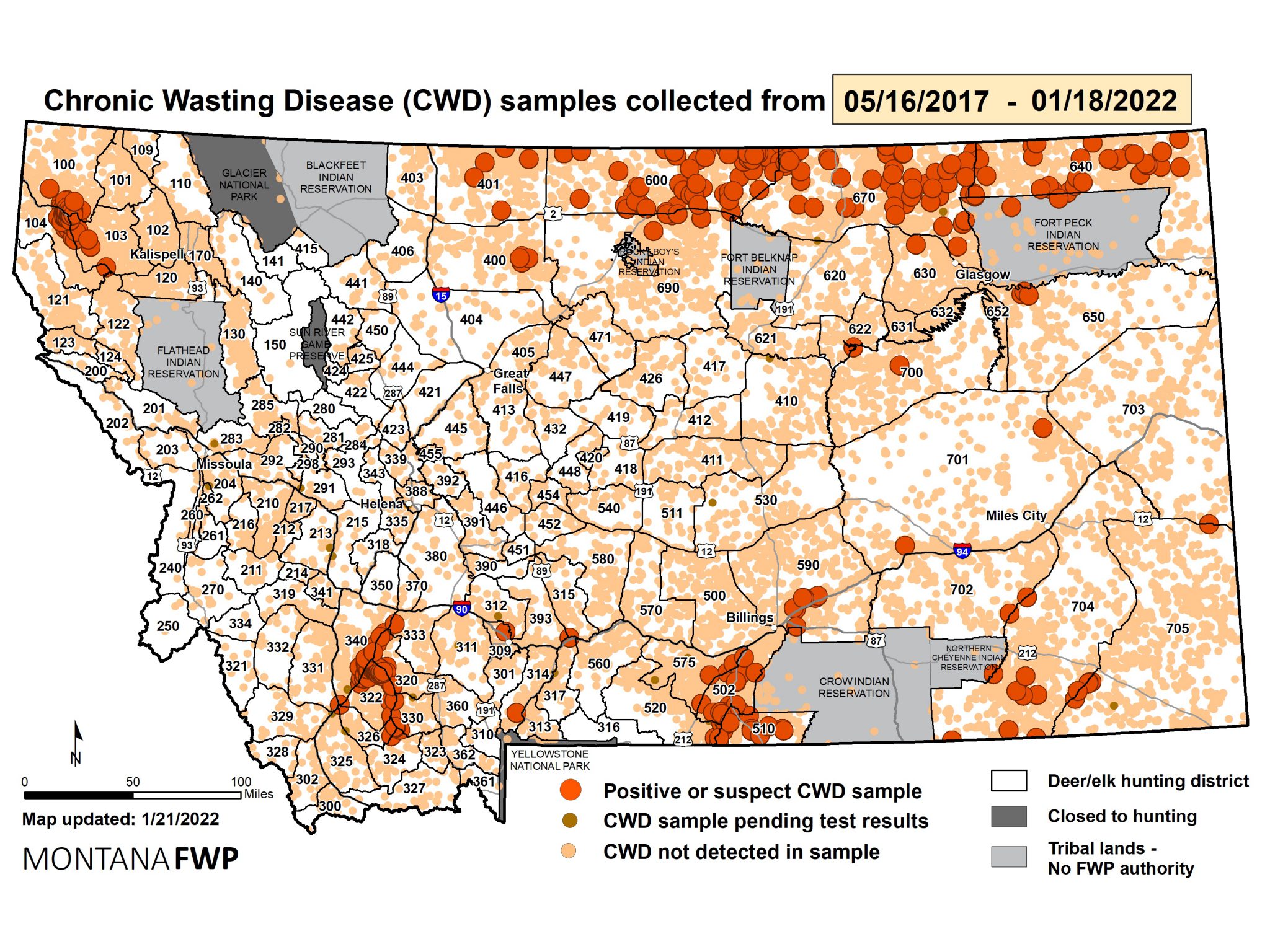

According to the CDC, the disease was first found in captive deer in a Colorado research facility in the late 1960s and in the state’s wild deer in 1981. Northern Colorado and southern Wyoming reported animals with the disease by the 1990s. Today, there are 27 states affected by CWD, including Idaho, which reported its first cases this season.

CWD was first detected in a mule deer in Montana in 2017. The first whitetail deer in the state infected with CWD was found in 2019 in the Ruby River Valley, where we’ll be hunting.

RELATED – Idaho to Hold CWD Hunt, Joins 26 States Battling Disease

CWD Testing — Behind the Scenes

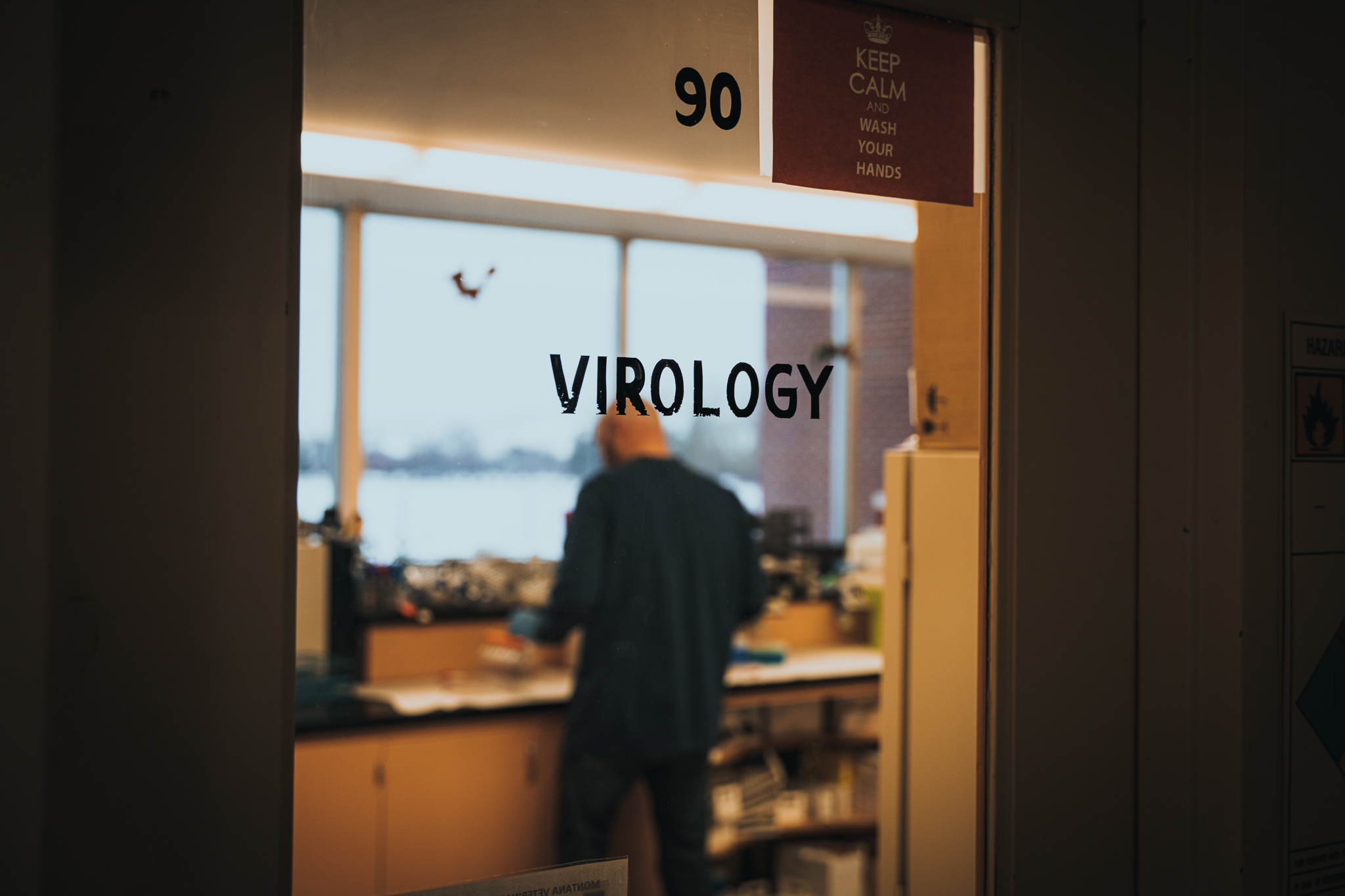

From the outside, the MVDL building looks like an old elementary school — a dusty relic among all the new development exploding in the area. Inside, it’s a 1970s-era labyrinth of hallways with various labs tucked behind keypad-locked, half-glass doors with hand-lettered department names.

When a hunter checks in a deer for testing, even those who are regulars at the deer-check stations or the FWP office in Bozeman aren’t aware of the lab’s existence. The MVDL is the ether into which their samples disappear while they wait for the results.

And yet, Dr. Erika Schwarz and her team are the ones who actually determine whether a deer being tested is clear to butcher or needs to be disposed of.

Schwarz is the head of Bacteriology, Virology, Serology, and Molecular Diagnostics at the lab. She is responsible for overseeing CWD testing, along with screening for dozens of other diseases and infections that show up in both wild and agriculturally raised animals of Montana.

As the only CWD testing lab in the state in its second year of operation, Schwarz and her team have processed roughly 9,000 samples this season alone, one from each deer submitted for testing.

From 2017 to 2019, before it had in-state testing capabilities, the FWP sent every sample all the way to the labs at Colorado State University. Now, the department sends them, literally, across the street.

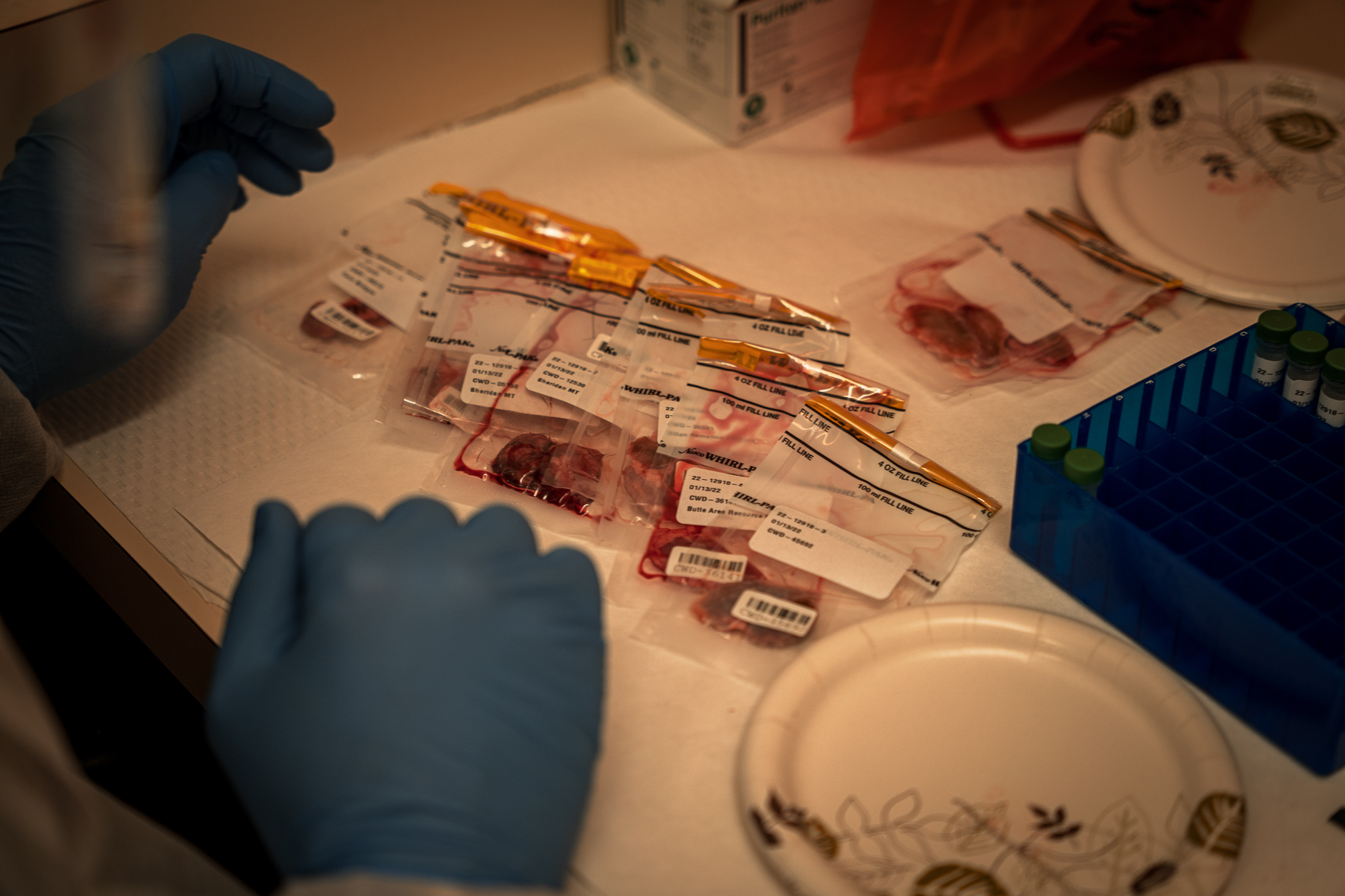

Schwarz unlocks one of the lab doors, and we walk into the sample intake and prep area. She reaches for a gallon Ziploc bag sitting on a stainless steel table with probably a dozen kits in it.

Each kit contains a portion of two retropharyngeal lymph nodes, each about the size of a kidney bean, from a deer’s neck, along with the cataloged harvest location and hunter contact information.

CWD prions accumulate in nervous and lymphatic tissues, like the spinal cord, eyes, brain, lymph nodes, and spleen. The nodes in the neck are the most accessible tissue that holds higher concentrations of the prions.

For moose and elk, the obex (located where the base of the brain and the spinal cord meet) is also required for CWD testing.

After cataloging the samples, the prep for the testing process starts.

“We have to manually section the lymph nodes and measure out a very specific amount of the cortex,” Schwarz says. “We have specific amounts that we have to use for the assay itself, which go into these tubes that have beads and a buffer solution. The tubes then go into the homogenizers, which spin them really fast, macerating the lymph node into a sludge.”

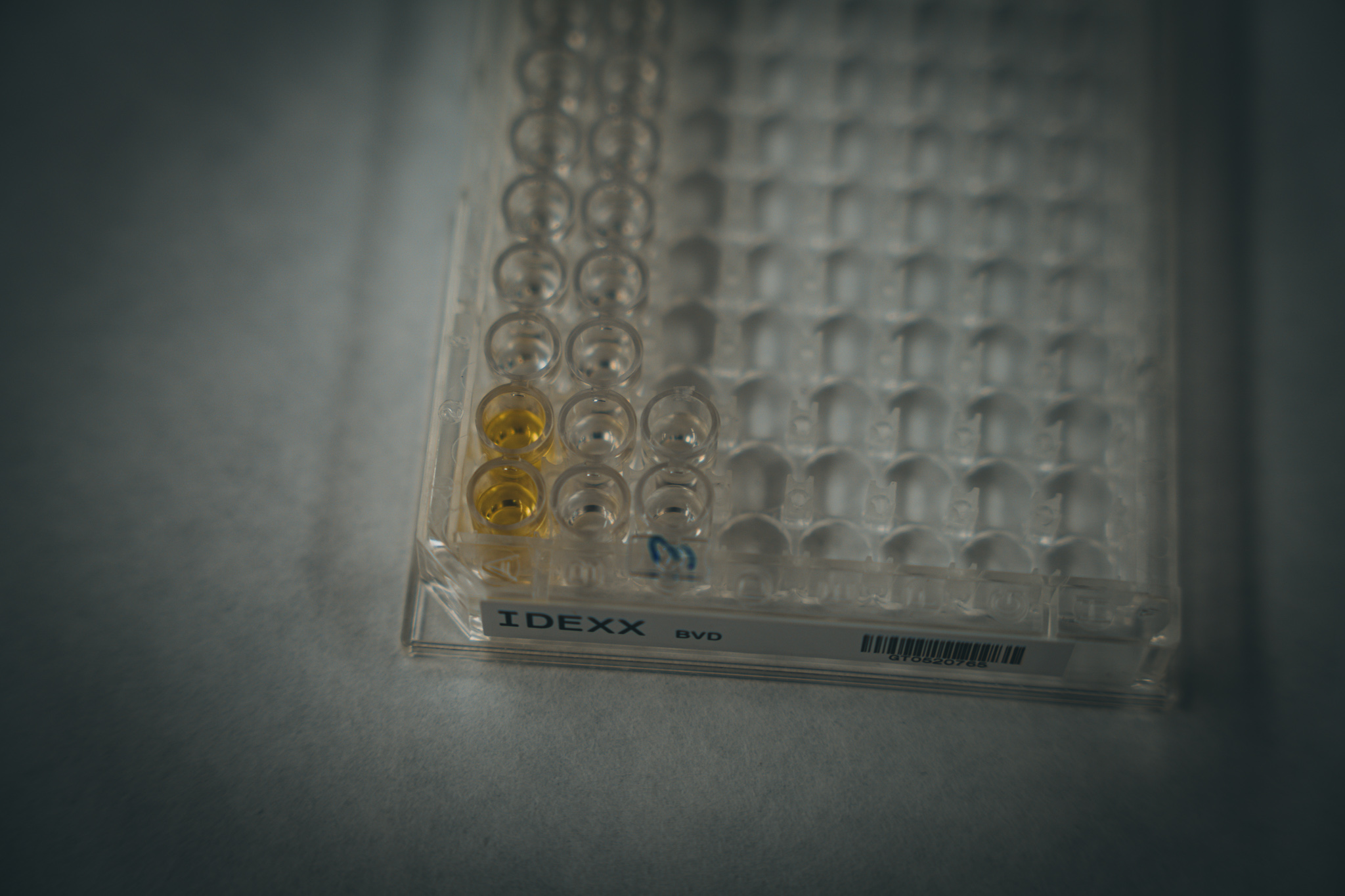

From there, we walk the small tubes to the virology lab. Brian Eilers, one of two microbiologists in the lab who handle the CWD testing, walks us through the actual enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, or ELISA, process.

“Once it’s all been homogenized, we take the liquid layer and put it in these plates that are coated with antibodies that pick up the prions,” Eilers says. “The plate goes into the ELISA machine, which runs the samples through a couple of different washing steps and then stains them.”

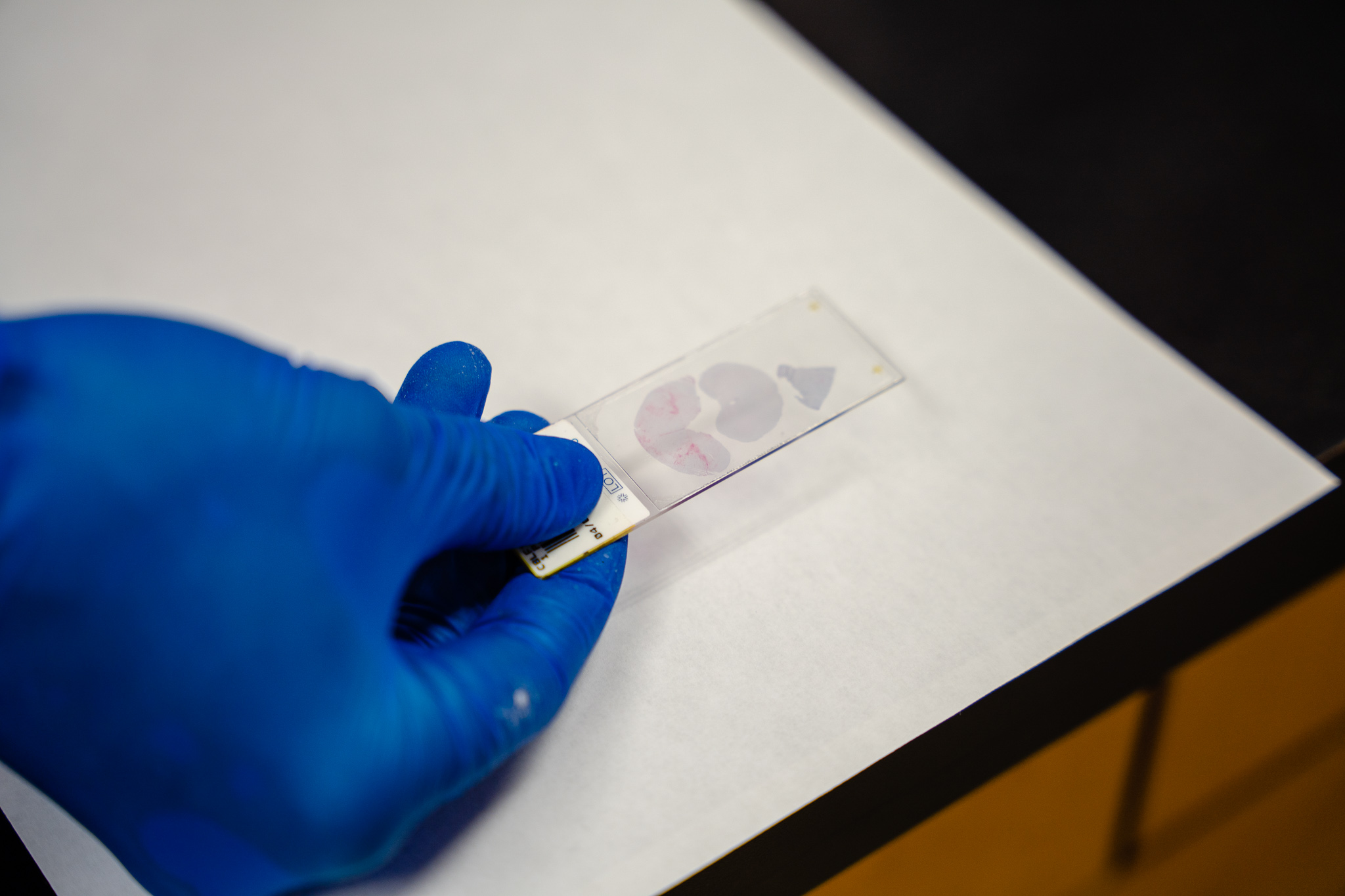

If the sample contains the antigen for the prion protein, you get a color change. If it’s yellow, it’s CWD positive. If a sample pops yellow, they then run it again from the beginning to double-check the result. Even with a second run, Schwarz says, there’s still one more step needed for confirmation.

“Those repeat positives are then sent to immunohistochemistry,” Schwarz says. “They’ll take a slice of tissue and stain it for the prion protein, just as a visual confirmation in that piece of tissue.”

Eilers offers some perspective on the time it takes to run the tests.

“Just to go through this process with 90 samples, once the samples are ground up, takes us about five hours,” he says. “To prep that many samples takes about two hours. So it’s a whole day, basically. Then if you have to repeat them, that’s another whole day.”

“In the highest season, it took us about 7 to 10 days to get the results turned around. But that’s because we’re getting, like, 1,000 samples a day,” Eilers adds.

Once every sample has a definitive positive or negative, the lab sends its results back to the FWP, which informs the hunters of the status of their deer.

MVDL’s capabilities are a huge asset to both wildlife managers and hunters, especially given that the FWP had to rely on Colorado State University’s lab only two seasons ago, where CWD testing was at the low end of the priority list.

“It just made sense to start testing here,” Schwarz says, “We have really good turnaround time, and FWP has been happy. We’ve had good participation and feedback from the hunters that submit, too. So I think it’s been successful.”

While hunters are required to stop at check stations heading to or from the field, even if they don’t have an animal, CWD testing is still voluntary.

“There seems to be pretty widespread support for the testing program, from hunters and from the scientific and the veterinary communities,” Schwarz adds. “It seems to be across the board. People want to test. They want to submit the samples and know more.”

RELATED – COVID Deer Update: Wisconsin Tells Hunters to Mask Up

Deer Heads and the Million-Dollar Question

The next morning we meet Emily Almberg, a disease ecologist in the FWP’s Wildlife Division, and Austin Wieseler, a wildlife health biologist, at the division’s necropsy lab in Bozeman.

The open bay is bright, well organized, and smells like a mix of bleach and cold viscera. A band saw sits next to the overhead garage door, and the center of the bay is occupied by a giant stainless-steel table — large enough, I expect, to hoist a moose onto if need be.

Almberg opens an equally giant door to a walk-in freezer where a euthanized bighorn ram, a few turkeys that had dropped dead in someone’s yard, and two contractor-size clear plastic bags with a half-dozen whitetail deer heads in each are being stored.

This is the home base for the state’s Wildlife Health Program. Anything dead or of interest in the world of wildlife health comes here — from rabies and tuberculosis to CWD and more. This is where all hunter-submitted CWD samples are organized before heading to MVDL.

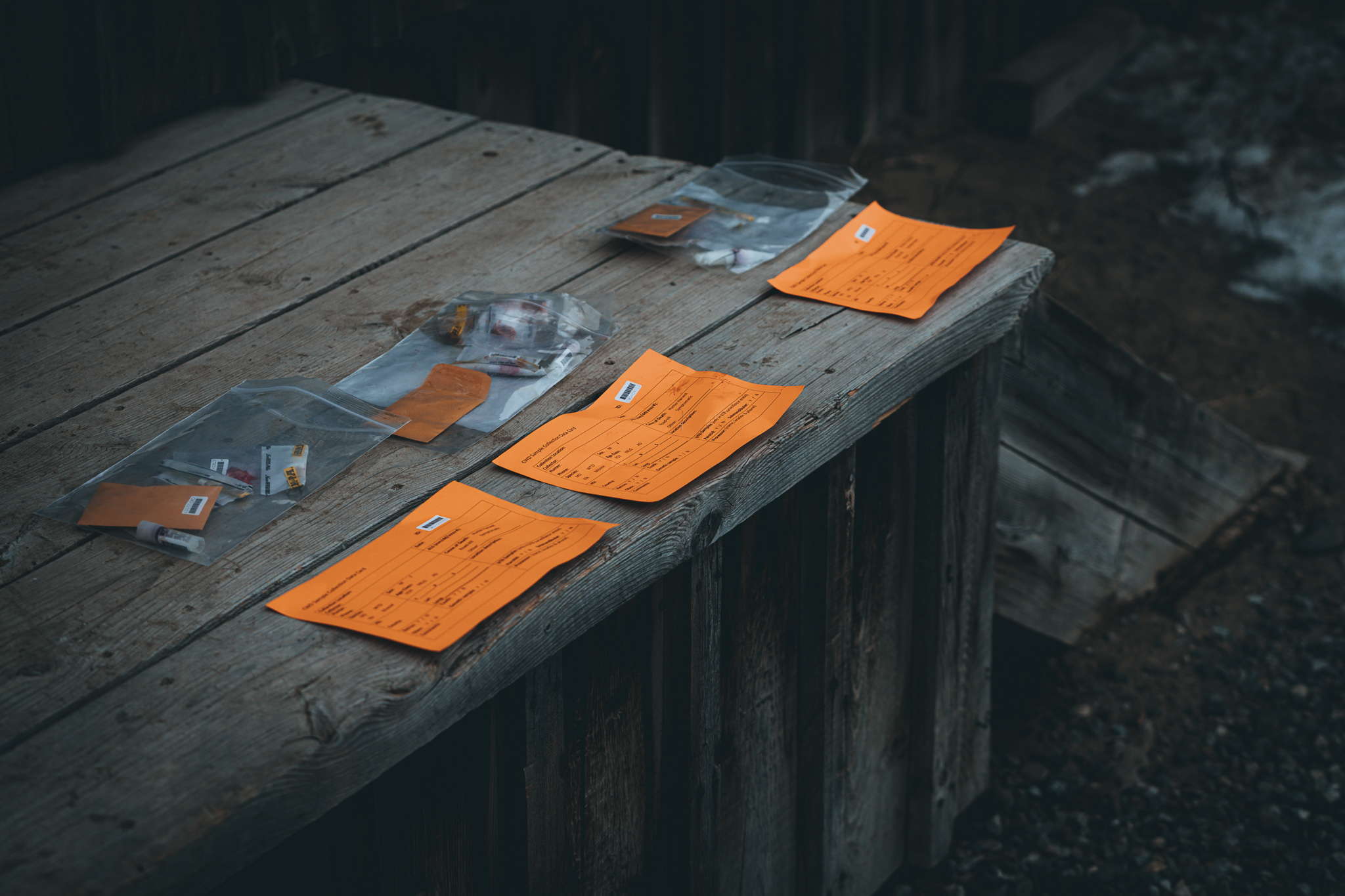

Almberg carries a doe head to the table to show us the sample collection process. Wieseler grabs a quart-size Ziploc bag containing two smaller roll-sealed baggies, a business card–size manila envelope, a small screw-top plastic vial, a foil-sealed scalpel blade, a blank hunter/harvest information card, and an FWP business card with a CWD tracking number.

As she cuts the doe’s throat from ear to ear, exposing the esophagus and lower jaw, Almberg explains that the vast majority of sampling is done in the field at FWP check stations. There are hunters who bring heads directly to their office, though.

“Typically, we’ll take one half of each lymph node and set them into two batches,” she says while locating and removing the nodes. “One of those will be archived, and one will be sent to the lab for testing.”

“We also take a little bit of genetic material,” she adds, cutting a small pinch of neck muscle and placing it in the tube. “This is just something we bank for genetic work down the line. A lot of studies have looked at a couple of different alleles that seem to relate to the severity of disease and the length of the infection.”

“They’ve been able to document shifts in those alleles as the prevalence of chronic wasting disease increases,” Almberg says. “So, they’re seeing selection. You know, I think folks hope that would generate a truly resistant animal. And who knows, maybe that’s possible. I don’t think they’re seeing evidence for 100% resistant animals yet.”

“Over time, we expect evolution,” she adds. “We don’t know if that’s just going to be an evolution toward a much longer course of infection, though. So maybe instead of two years, they’ve got five years to live before they die. I don’t know. It’d be great if there was true resistance.”

The last item she collects is an incisor, which goes in the small manila envelope that’s sent to Deer Age for analysis. Teeth collected from deer over the first several years are now starting to reveal age data about disease prevalence in year classes.

“One of the tasks in the next several months is to work on that data and look at age prevalence because it does tell you how quickly CWD is circulating. If you see a really high amount of exposure among young animals, you know, that force is quite high,” she says. “Age prevalence data is a little more sensitive to changes in dynamics than just using the total prevalence that we get from everything together.”

A big driver of prevalence is population density. For instance, in the Ruby River Valley, where the state’s first whitetail CWD case was located and where we’ll be hunting, concentrations of deer are extremely high, and so is the prevalence of CWD.

The Ruby River Valley population is contiguous with other whitetails, elk, and moose throughout the Jefferson, Beaverhead, and Big Hole valleys. The spread of the disease through contaminated landscapes and direct transmission in dense populations makes it almost impossible to manage.

“The million-dollar question is how do we effectively control it,” says Almberg. “Can we do anything? Over the last four or five years, Western states and provinces have come together with a series of tools we think might work. Things like density reductions, buck harvest in mule-deer-driven systems, limiting agricultural attractants that bring lots of animals together, and finding ways to reduce the density of those in the landscape so that we have fewer points of transmission.”

As of 2019, all but six states in the lower 48 have banned the import of high-risk parts of ungulates. In October of 2021, Rep. Ron Kind of Wisconsin and Rep. Glenn Thompson of Pennsylvania introduced the Chronic Wasting Disease Research and Management Act in Congress. The bill would earmark $70 million annually to combat CWD across the country.

“No one expects to have immediate answers. I mean, all these questions are on a 5-to-10-year timescale,” Almberg adds. “But we’re trying to have multiple states implement similar tools and monitoring.”

“There’s evidence in Colorado, for example, that among mule deer, bucks can drive a high proportion of the dynamics in the system,” Almberg continues. “Keeping buck densities low seems to slow the epidemic growth rate. We’ll see with more states replicating some of that management if that pattern holds.”

Beyond the known avenues that disease transmission occurs — contact with urine, feces, saliva, and blood — the contact-by-extension possibilities that aren’t yet scientifically proven loom frustratingly large because prions are so persistent in any environment.

There has been anecdotal evidence that suggests a CWD-positive moose was infected by inhaling dust, either from agricultural feed or dry ground, that had prions attached to the particles.

Also, prions attaching themselves to boots, clothing, or other gear is possible, opening the door for transport to other locations, much like invasive species that have forced state and national regulations in rivers, lakes, and woods across the country.

RELATED – Yellowstone Bison Herd to be Culled by 500 to 700 Animals, no New Hunt

64 Deer Per Square Mile

The evening before our hunt, our host Dustin grills a pile of caribou, sheep, and elk meat, along with mule-deer-and-blue-cheese brats and whitetail brats. Originally from Illinois, Dustin is a chief with the Big Sky Fire Department, a dead-eye waterfowling fanatic, and a big-game hunter. He and his family have lived in the Ruby Valley for 10 years now.

Dustin’s buddy Dean Waltee, a wildlife biologist with the FWP, joins us for dinner, along with a few other friends. Knowing that we traveled here to get a complete picture of the CWD issue in southwest Montana, the conversation quickly turns to population density and infection rates.

“From 2015 through 2020, I observed an annual average of 64 whitetail deer per square mile within the lowest 20 square miles of the Ruby River Watershed at spring green-up,” Waltee says. “This represents the lowest point of the annual population cycle — post-winter and pre-fawn-drop. Following the 2020 general hunting season and CWD management hunt, the observed density within this area reduced to 35 per square mile.”

The booming population is the result of Montana’s successful decades-long deer and habitat management efforts. Unfortunately, pockets of deer are now stacked up in resource-rich areas like the Ruby Valley and transmitting the disease.

“The initial 161 samples collected during the 2021 hunting season from that same area showed a CWD prevalence of 45% across all deer,” Waltee says. “Prevalence was 58% among adult bucks, 46% among yearling bucks, 30% among does, and 10% among fawns.”

Fortunately, the good bourbon comes out, and conversation pivots to humorous hunting stories.

RELATED – New Animal Tracking Software: Hunting Conservation Game Changer?

CWD–09712, 10571, and 22007

It’s a crisp 15 degrees as we roll out in the truck to scout for deer at 7:30 a.m. With all the talk of population density in the previous few days, I’m expecting to see herds of whitetails running like American bison before the 1830s.

Other than watching tails bound away at the sight of the truck and inadvertently spooking a group of about 12 deer while stalking a good buck and two does, the morning is quiet. We retreat to the truck, ditch a couple of layers, and hit the road for another scout.

On our patrol, we spot several deer moving along a hedgerow of buckbrush and willows about 200 yards away. Dustin estimates their intended direction and drives a quarter-mile farther before pulling off the road.

After a stalk of about 100 yards, we have plenty of cover and a decent position if the deer keep moving in our direction. The group shows up and then hangs in the thick stuff just over 200 yards away.

It’s too open to try and stalk closer, especially as spooky as they are, and I’m not shooting off-hand that far through a softball-size opening in the brush with a 7mm Rem Mag. My buddy extends the legs on his camera tripod and hands it to Dustin, who sets it up in the snow in front of me.

I rest the back of my hand on the tripod’s plate, find my mark, take a few breaths, and squeeze the trigger.

Crack.

I hear the heavy thump of the bullet finding its target, and then all hell breaks loose before I’m even able to acknowledge what happened. Roughly 20 deer blow out of the thicket, their white tails flagging their way across the open field.

“A hundred and fifty yards out. By that last patch of brush,” Dustin says as he points out a doe.

Crack.

“One twenty-five. Straight out. See her?” Dustin points again.

“Yeah,” I say with an exhale.

Crack.

My three tags are filled, and now the dirty work begins.

At the check station, I close the loop on what I’ve learned over the last few days, collecting the lymph nodes, a pinch of neck muscle, and one incisor from each of the three does, now known as CWD–09712, 10571, and 22007.

The samples will head to the FWP to be entered into their system, then forwarded to MVDL for Schwarz’s team to homogenize the lymph nodes and run them through the ELISA machine. According to statistics, one of the three deer should test positive for CWD. I’ll get an email in about a week with the results.

If any of them come back negative, though, I’m definitely getting the meat ground and shipped to me in upstate New York. Waste not, want not.

RELATED – Montana Elk: New Regs Could End Hunting on Some Public Land

CWD Awareness and Participation

As excited as I was before flying to Montana to be part of this management hunt, I knew this was going to be a conservation effort first and foremost. I didn’t come here to hunt — at least not in the same sense that I do in the whitetail woods of western New York. I was going to cull animals from a herd that is biologically unhealthy.

Even so, the firsthand look at CWD, from field to forensics, is about as profound as any hunting experience I have ever had. It’s certainly a sobering and cautionary message for any hunter that values the health of wild deer, elk, and moose populations across the country.

To see dozens of whitetails on the hoof in the expanse of ag fields is special — flecks of tan in willow-filled river-bottom, buckbrush thickets, and swale nestled between the Tobacco Root Mountains, the Ruby Range, the Greenhorn Range, and McCartney Mountain.

But understanding that half of them are dead deer walking just hits different. Equally concerning is that the spread of CWD to populations and states that haven’t yet detected the disease is more than just a hypothetical possibility.

There are simply too many unknowns about alternate modes of transmission, and in regions that have yet to report CWD, hunters are still in the dark about how pervasive and deadly the disease is in deer.

States have a responsibility to try and get ahead of the inevitable spread of CWD, but hunter awareness and participation will be the lynchpin of any management effort to control the disease — here in Montana or anywhere else our beloved deer, elk, or moose roam.

UPDATE – Jan. 26: I received the results of the CWD tests from the FWP on Jan. 25, one week after submitting them. The statistics held true and one doe, CWD–10571, came back “SUSPECT,” which means it tested positive twice for the disease. The FWP treats all “suspects” as positives since their previous experience indicates the ELISA & IHC tests nearly always agree. The two other deer will be processed in Montana, frozen, packed in coolers, and shipped to my buddy in Illinois and me in western New York to enjoy over the wait for next deer season.

READ NEXT – Chronic Wasting Disease Outbreak: Wyoming Collects 1,000s of Samples

Comments