James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok is remembered for several things: his famous nickname, his proficiency with his signature nickel-and-ivory Colt Model 1851 Navy revolvers, and the final hand he was dealt in poker that directly preceded his coldblooded murder. After a life packed with astonishing stories and deeds, Hickok is, in the end, most remembered for how he died 145 years ago in August 1876.

Early Years

Born to an abolitionist family in 1837, Hickok grew up in Illinois and left home when he was 18. He made his way to Kansas and teamed up with a group of anti-slavery jayhawkers making a name for themselves during the violent Bleeding Kansas era of the 1850s.

Hickok was not yet 21 when he began his career in law enforcement by getting himself elected as a constable in Johnson County, Kansas, in 1858. During the Civil War, he was employed by a local provost marshal to keep tabs on drunken Union soldiers and debtors to the Union Army. In the fall of 1865, he was recommended for the position of deputy federal marshal at Fort Riley, Kansas.

In His Prime

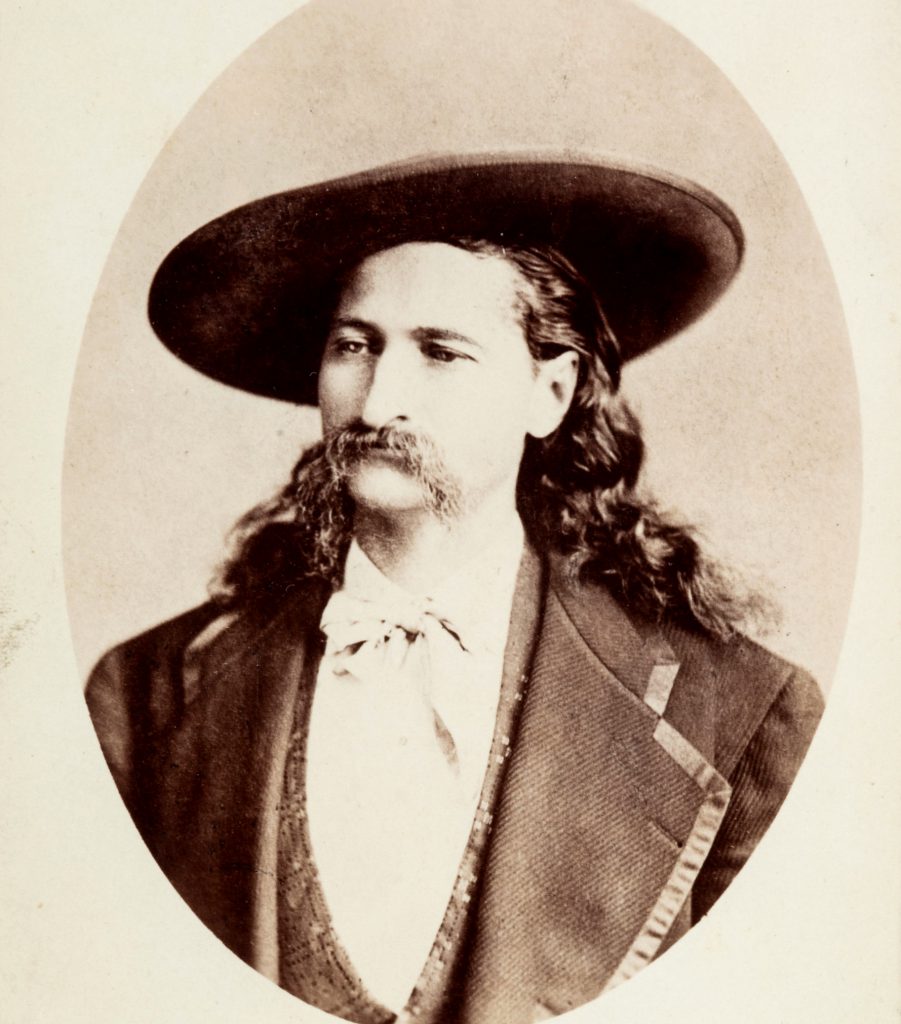

By 1867, Hickok had already been a minor regional celebrity for a few years, mostly due to his prowess with a pair of pistols. When George Ward Nichols asked to write a story about him for the February 1867 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (today known as Harper’s Magazine), Hickok obliged, saying, “I’m sort of public property.”

Nichols described Wild Bill as standing “six feet and an inch in his bright yellow moccasins. A deer-skin shirt, or frock it might be called, hung jauntily over his shoulders and revealed a chest whose breadth and depth were remarkable. […] His small, round waist was girthed by a belt, which held two of Colt’s navy revolvers. […] Yes, Wild Bill with his own hands has killed hundreds of men. Of that I have not a doubt. ‘He shoots to kill,’ they say on the border.”

With that big-time magazine story, James Butler Hickok truly became Wild Bill Hickok and was propelled into the national spotlight for the first time.

After getting famous, Hickok became a deputy US marshal, a city marshal, and a county sheriff in the short time between March 1868 and August 1869. But he didn’t like to stay in one spot for long and continued to take different jobs throughout the West.

During the American Indian Wars, he worked for a good while as a scout for the Army, where he hung out with another famous Bill of the era: “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who was nine years his junior. The men had known each other for more than a decade by this time, dating back to Hickok’s stint with the Kansas jayhawkers.

Hickok also ran into some notorious outlaws. On one occasion, he took John Wesley Hardin’s revolvers off of him in Abilene, Kansas. Hardin was using an alias at the time, so Hickok didn’t know it was him.

Health Problems, Gambling, and Deadwood

By 1876, Wild Bill’s health had begun to deteriorate. Glaucoma and ophthalmia were robbing him of his once keen eyesight, and along with it, the shooting ability that had made him famous.

One of Hickok’s greatest vices in life was gambling, and in his later years, he really leaned into it. He was typically a pretty good poker player and rarely passed up the opportunity to play cards.

On Aug. 1, 1876, Hickok was playing poker at Nuttal & Mann’s saloon in Deadwood, an upstart mining town in the Dakota Territory, and he was winning. He took pity on a fellow card player, Jack McCall, who was losing badly. Hickok persuaded McCall to step away from the table until he could cover his losses. He even offered him money for breakfast. McCall, who was quite drunk, accepted Wild Bill’s offer and money but was secretly offended by the gesture.

The following day Hickok went back to the saloon looking for another card game. Having made his fair share of enemies over the years, he always preferred to sit with his back to the wall and facing the door when playing cards so he could keep an eye on everyone who walked in. That’s good situational awareness, even in modern times.

However, when he walked into Nuttal & Mann’s that day, the only open chair at the poker table was facing the wall. A man named Charles Rich was in Wild Bill’s preferred seat. Hickok asked Rich to switch, and Rich refused twice.

Unfortunately, Hickok’s desire to play cards trumped his desire to watch his own back. He settled into the game and couldn’t see McCall when he entered the saloon, intent on getting retribution for the perceived offense from the day before.

McCall walked up to Hickok from behind and shouted, “Damn you! Take that!” as he shot him in the back of the head from spitting distance with a .45-caliber Colt Single Action Army revolver.

Hickok died instantly at the card table. So the legend goes, the poker hand he was dealt just before being shot consisted of two pairs: the deck’s two black aces and two black eights. Apparently, nobody took note of his hole card. That’s why, to this day, a poker hand with black aces and eights is known as the “dead man’s hand.”

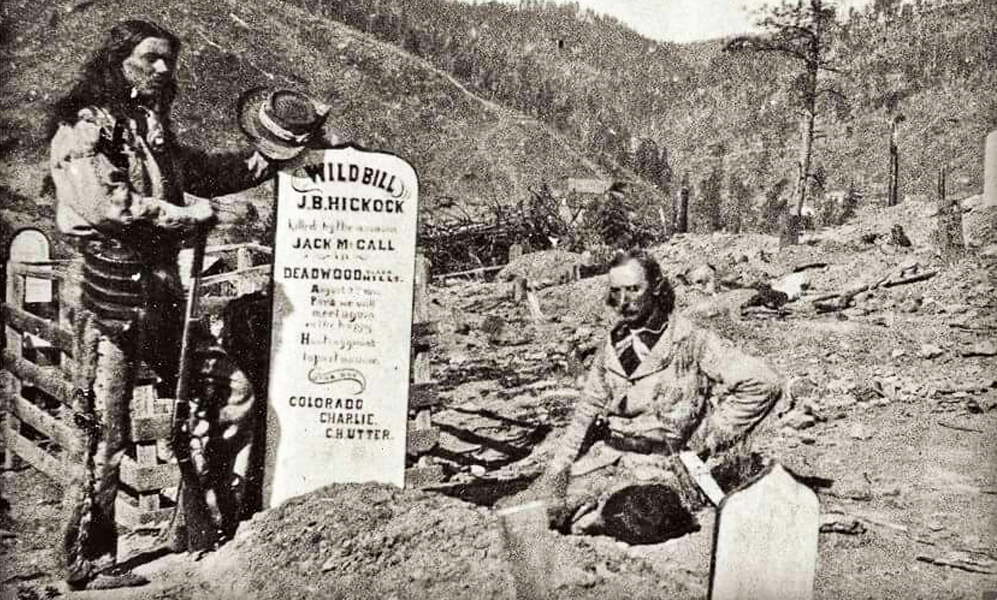

Wild Bill Hickok, legendary lawman and gunslinger, had been unceremoniously shot in the back by a bitter, drunk card player, and was laid to rest the next day in the town’s Ingleside Cemetery. He was just 39 when McCall murdered him on Aug. 2, 1876, and yet he’d already amassed enough experiences and tall tales to ensure his legend and legacy lived on long after he was gone.

McCall was tried for murder in Deadwood soon after his crime in front of an ad hoc jury. The fact that he shot Hickok was indisputable. McCall’s shaky defense claimed he killed Wild Bill as revenge for Hickok’s having killed McCall’s brother back in Abilene. It was enough for him to be released, and he promptly got out of town.

After later bragging about killing Wild Bill to anyone who would listen, McCall was eventually taken into custody by the US Marshals Service and transported to the city of Yankton, where he was tried again for Hickok’s murder, convicted, and hanged. If he’d hadn’t shot Hickok, McCall wouldn’t be remembered at all.

Wild Bill’s Legacy

Hickok was initially buried in Deadwood’s original town cemetery in 1876, but he would only rest there for three years. The old cemetery was in the way as the town grew, and the graves were relocated to the nearby Mount Moriah cemetery where Hickok’s headstone stands today.

In 1891, a red sandstone bust of Hickok was carved and erected as a memorial. However, pilgrims to the gravesite made sure the effigy didn’t last long. In about a decade, souvenir seekers had chipped away the entire head, leaving just the shoulders.

The bust’s remnants were taken to the Adams Museum in Deadwood, leaving Wild Bill’s grave relatively unadorned for the next century. In 2002 a retired high school art teacher decided to re-create the original sandstone bust. This time Hickok’s likeness was wisely cast in bronze and has so far stood up well to about two decades’ worth of tourists.

Hickok continues to be one of the most recognizable personalities of the Wild West, a distinction bestowed upon him in life and death. His name belongs alongside legends of the era like Jesse James, Wyatt Earp, Billy the Kid, and Buffalo Bill Cody — and while Nuttal & Mann’s saloon is long gone, a wooden sign still marks the spot in Deadwood, South Dakota, where Wild Bill died.

Read Next: Fact vs. Fiction in HBO’s Epic Western ‘Deadwood’

Comments