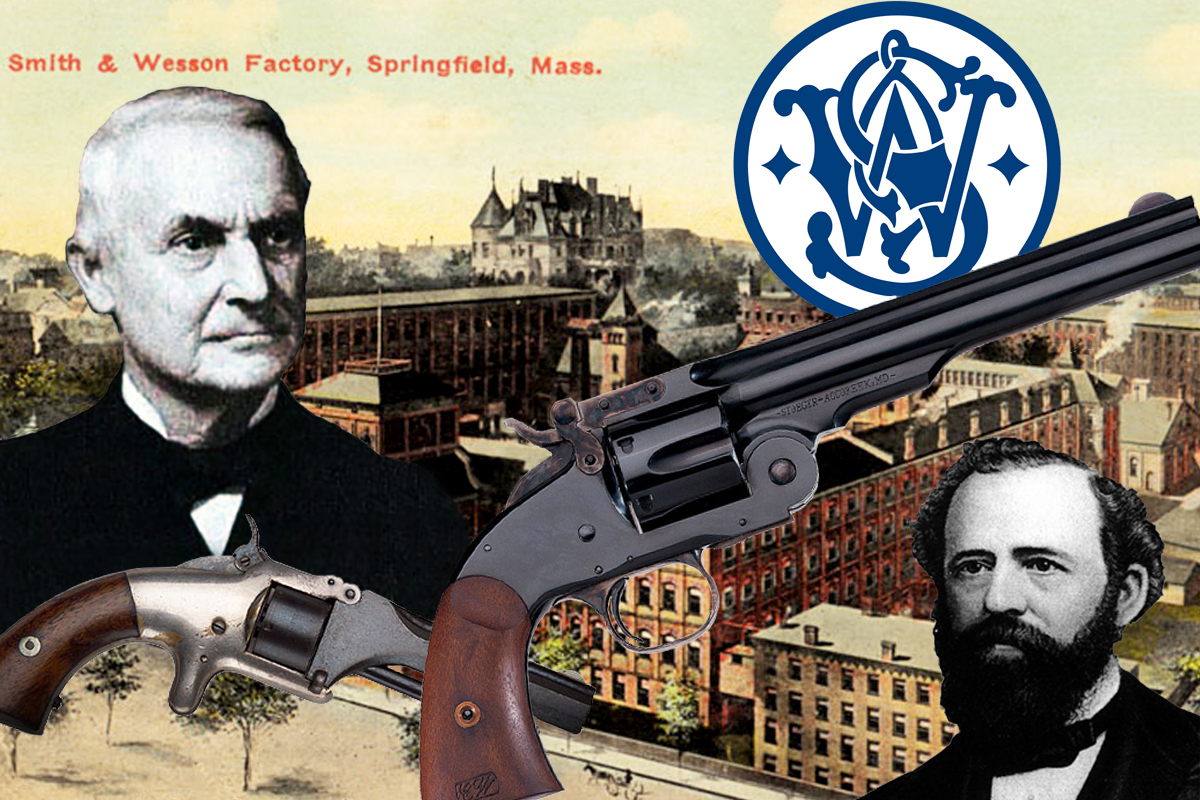

The names “Smith” and “Wesson” sound as natural together as Lewis and Clark or Tom and Jerry. The S&W brand has been a mainstay of the modern gun world practically since it began in the 19th century. It can be easy to forget the gun-building giant bears the surnames of two very real people who made an indelible imprint on firearm design and gun history. The elder half of the duo that helped pioneer modern American gun making was Horace Smith, a small-town guy from a little place called Cheshire, Massachusetts, who worked with guns almost his entire life.

Smith was born Oct. 28, 1808, and by the time Smith & Wesson got up and running, he’d already had an impressive 28-year career working with some of the era’s most prominent names in firearms, like Springfield Armory, Eli Whitney, Allen & Thurber, and Robbins & Lawrence.

Horace Smith: The Early Years

In 1812, when Horace was four, his family moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, where his father took a job at Springfield Armory, the larger of the two federal armories and of absolutely no relation to the gun company that exists today.

Related: Texas City Disaster of 1947 – Deadliest Industrial Accident in US History

When Horace turned 16, he followed in his father’s footsteps and began an apprenticeship at the government-run armory. One of the first jobs he held there was as an assistant to a bayonet forger.

Four years later, in 1828, he became a journeyman and worked in several departments at the armory. He had a particular knack for inventing machinery to make gun parts and is credited with creating the machine at Springfield Armory used for checkering hammer spurs.

Smith Meets Wesson

After 18 years in the employ of Uncle Sam, Smith moved to Connecticut and took a job as a toolmaker for Eli Whitney — you know, the guy you had to learn about in school because he invented the cotton gin and changed the textile industry forever.

The job was short-lived, and he soon moved on to Allen & Thurber, a company best known for its pepperbox pistols. There, Horace began making a very different kind of gun. He worked with Ethan Allen (no relation to the Revolutionary War Ethan Allen) to make whaling guns and barrels. Smith is even credited with inventing an exploding projectile designed to be used with them.

Details are hazy about what Smith was doing from 1850 to 1852, but we know he moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1852 to work for the tool company Allen, Brown & Luther. During this time, he met Daniel Baird Wesson as he was working on designs for what would become the wave of the future in gun design: repeating firearms. He didn’t know it, but it would be the most important meeting of both men’s lives.

Related: The Chuck Wagon – The History of America’s First Food Truck

The first repeater project Horace worked on that we know of was a magazine-loaded pistol invented by Orville B. Percival and Asa Smith that Horace built in 1850.

It was a busy time in Smith’s life. Courtland Palmer soon hired him to work on improvements to the lever-action rifle invented by Walter Hunt and Lewis Jennings. In 1851, Smith was granted a patent assigned to Palmer for improvements on the lever-action rifle. Wesson knew of the rifle, too, and the two men presumably bonded over the design, its shortcomings, and their ideas for improving it.

The Beginning of a Beautiful Partnership, Take One

In 1852, Horace Smith and D. B. Wesson formed what would be the first of two eventual partnerships. They began producing the Volcanic line of repeating rifles and pistols as the Smith & Wesson Company. These guns were among the first functional repeaters, and they fired a primitive metallic cartridge ammunition called Rocket Ball ammo.

Like so many small 19th-century arms makers, the company soon succumbed to financial issues in late 1854. Smith and Wesson’s first partnership was dissolved early the following year, but the company didn’t go anywhere. It had a new owner by the name of Oliver Winchester, who reorganized the company and renamed it Volcanic Repeating Arms. That didn’t change the fact that the Volcanic guns and ammunition were unreliable, underpowered, and unpopular.

Related: What Happened to William Clark After the Lewis and Clark Expedition?

Wesson stayed on as the acting plant superintendent of Volcanic while Smith returned home to Massachusetts and worked with his brother-in-law in a livery stable.

Let’s Try This Smith & Wesson Thing Again

The two soon-to-be titans of the arms industry weren’t apart for long. They met on Nov. 17, 1856, and an entry in a factory ledger from the following day notes the formation of a new Smith-and-Wesson partnership.

Wesson contributed $2,003.63 and Smith put up $1,646.68 for the venture, and just like that, they were off and running. Their first big move was to capitalize on an innovation Samuel Colt brushed off when it was presented to him by one of his employees, Rollin White. His bored-through revolver cylinder would make it possible for wheelguns to work with new metallic cartridges that were being perfected at the time.

Sam Colt certainly saw the advantages of building guns with interchangeable parts, but his forward-thinking failed him in this case.

Related: How Western Legend Wild Bill Hickok Died in Deadwood

When Colt ignored his invention, White quit his job at Colt and sold the licensing fee for his patent on the bored-through cylinder to Smith and Wesson for $497, plus a royalty payment of $0.25 for every gun sold.

All told, it cost $4,147.31 (including White’s fee) for the two men to start a company that would go on to become a household name in the firearms business and, thanks to White’s patent, keep Colt out of the metallic-cartridge revolver business for many years. Adjusted for inflation, that’s approximately $133,000 in today’s money.

Horace Smith and Dan Wesson Build an Empire…Slowly

That initial startup cost paid off handsomely, but Smith & Wesson didn’t happen overnight. Thanks to supply chain and equipment acquisition issues, they only produced four guns in 1857.

However, by October 1865, just shy of nine years after they began their latest venture, both Horace and D. B. cleared $163,000 in annual personal income, and their company was competing with the likes of Colt in the handgun market. Today that would be the equivalent of $2.7 million. Springfield, Massachusetts, had more than 15,000 people at the time, and Smith and Wesson were the only two with six-figure incomes.

Related: 7 Great and Criminally Underrated Westerns

To put that in perspective, the same year, President Abraham Lincoln made $25,000, and a lieutenant general in the Union army made $8,976 a year.

The money was good, but everyone wants to retire eventually. Smith was 17 years older than Wesson, and he was more than ready to retire in 1873 at age 65. He sold his interest in the company to Dan Wesson, who was 47 at the time, on July 1 of that year.

Wesson was still in his prime, and under his direction, S&W grew even more than it had in the past.

Life After Smith & Wesson

Horace Smith had no intention of slowing down in retirement; he just wanted to stop working and spend his time doing other things. He traveled to see the Western frontier, became a student of astronomy, and devoted time and money to his church and the youth in his community.

Related: 10 of the Best Western Movies Ever Made

When he died on Jan. 15, 1893, Smith left behind a sizeable estate. After several bequests to relatives and institutions, his will provided the rest of his estate be used for public purposes at the discretion of his executors.

The Horace Smith Fund was established in 1899 to help deserving students finance their education through scholarships and fellowships, and it’s still around today and available to students in Hampden County, Massachusetts.

Horace was laid to rest in the Smith family plot in Springfield. His individual headstone in the plot is very simple, giving no indication of his tremendous impact on the firearms community and world history.

Read Next: Hunting History – How Firearm Tech Changed the Way Americans Hunt

Comments