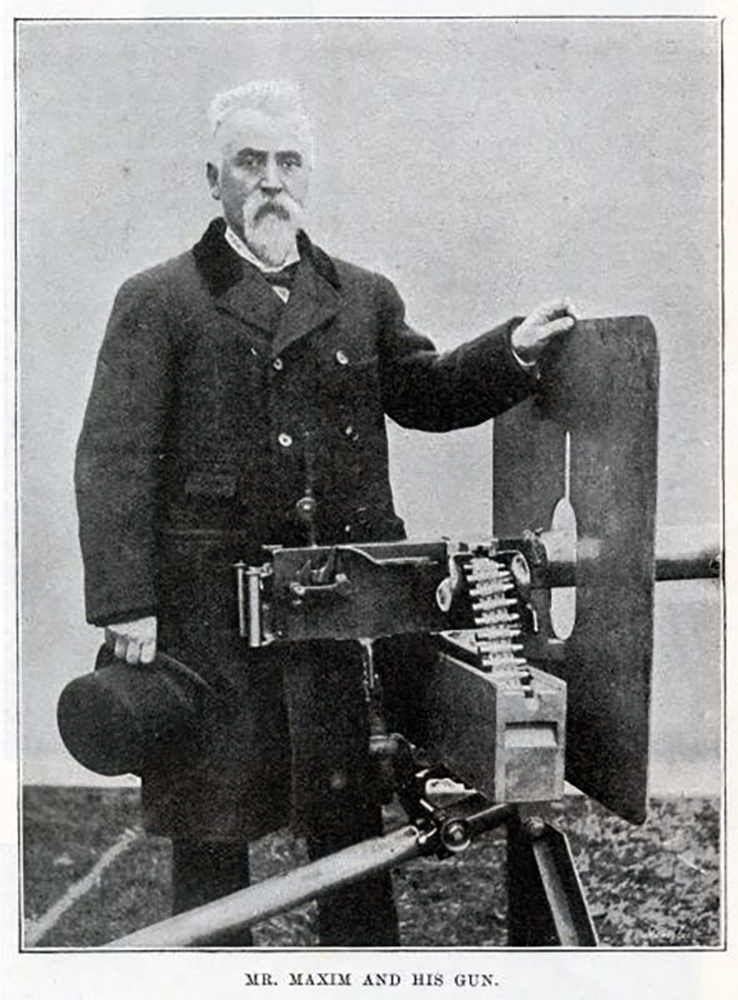

The United States is often called the “Land of Opportunity,” but for Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim, that wasn’t exactly the case. This week marks the 105th anniversary of his death, and the story of his life is a remarkable one full of near successes and one tremendous success that would literally change the world and make the name “Maxim” at once famous and infamous.

After being born in Maine in 1840, Hiram tried for years to find success working at a variety of professions during his first 40 years. It wasn’t until he moved to Europe as he approached middle age that things really took off for him.

One could argue the only success he achieved stateside came in the form of his son, Hiram Percy Maxim, who would go on to become a famous inventor in his own right. He’s often confused with his father thanks to his most famous creation: the firearm suppressor, or The Maxim Silencer, as he called it.

Hiram Stevens Maxim invented a wide variety of items that never fully panned out for him. He developed medicinal inhalers, steam engines, internal combustion engines, lightbulb components, riveting machines, devices to prevent ships from rolling, a curling iron, automatic fire sprinklers, and flying machines. None of them brought the level of success he desired.

He reportedly told a newspaper that, while in Vienna in 1882 and searching for a cutting-edge project to work on, an American colleague quipped, “Hang your chemistry and electricity! If you want to make a pile of money, invent something that will enable these Europeans to cut each others’ throats with greater facility.”

Hiram took this advice to heart and began work on the one thing for which he would forever be remembered: the machine gun.

Right On The Cusp of Full Auto

Maxim was in the perfect place at just the right time to create such a weapon, however, the machine gun would have undoubtedly come along in short order with or without him.

There were several firearms being used that were on the cusp of full-auto fire, namely the Gatling gun and the Gardner gun, both of which featured gravity-fed ammo hoppers and were powered by hand cranks. But fate placed Maxim in the path of history.

Both of these guns had significant drawbacks that made them troublesome for combat use. The hopper fed loose ammunition that could easily bind up and it required one man to feed it while another worked the crank at the optimal speed.

The guns used multiple rotating barrels to prevent overheating, but this made for a very heavy gun that needed to be carted around like a small artillery piece. The rate of fire and ammo capacity was limited, as was accuracy and range.

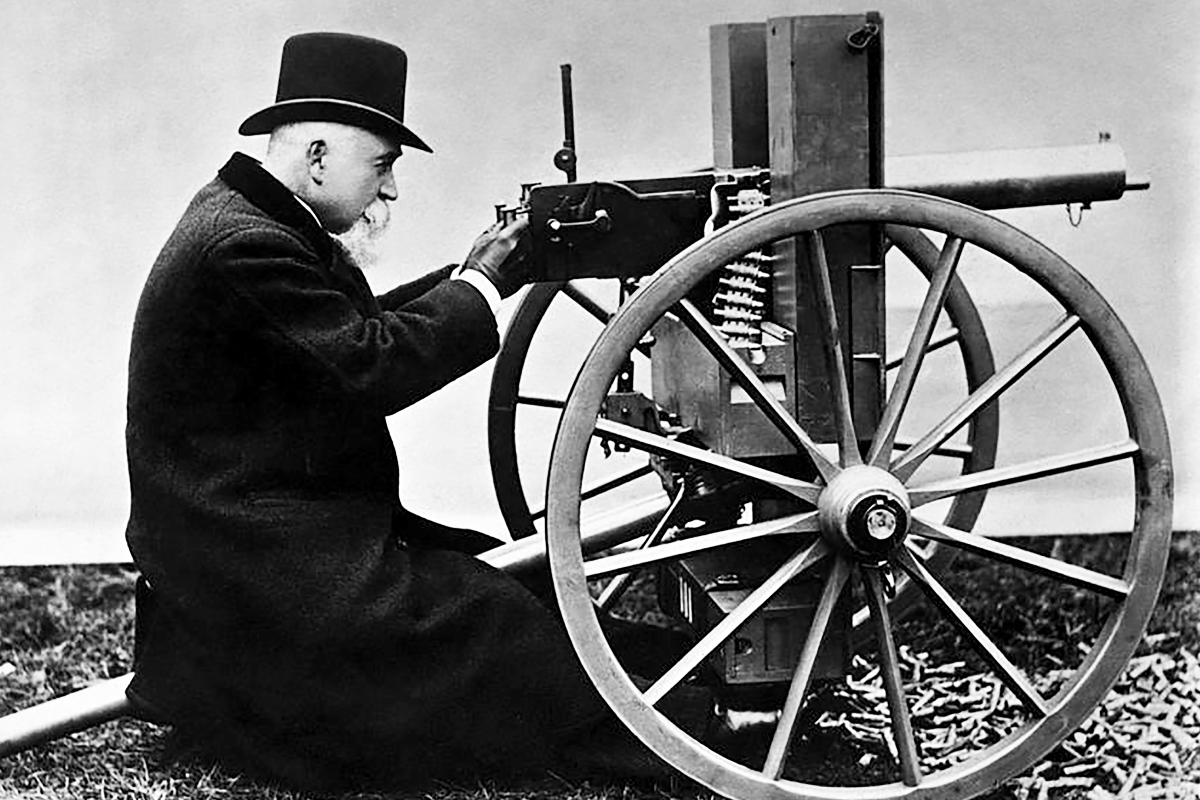

The Maxim gun used an early recoil-operated firing system — that is, a system in which energy from the recoil of a fired round acts on the breech block and is used to eject the spent casing and chamber the next round. This eliminated the need for mechanical cranking; the gunner just had to pull and hold the trigger. It was the first truly viable automatic weapon.

Also, instead of using multiple heavy barrels to prevent the bores from melting under sustained fire, Maxim’s gun used a single barrel encased in a cooling sleeve filled with water. This meant a water supply was required to run the gun, but it also meant the Maxim could fire longer at a rate of about 600 rounds per minute.

It was also designed to fire new high-pressure rifle cartridges loaded with smokeless powder, which greatly increased its power and range. And that ammo was belted, so no more hopper.

The gun had drawbacks: It was big and heavy, plus it required a firing team of four to six men to keep it running. In addition to the gunner, their jobs were to reload, spot targets, and tote ammo and water for the gun. They also had to move and mount it when necessary — another team effort.

Despite all that, it worked, and its advantages were such that it became a bloody gamechanger in warfare.

Maxim’s machine gun was introduced to the world in 1884. A century later, historian John Ellis said, “Without Hiram Maxim, much of subsequent world history might have been different.”

Testing Machine Guns in the Heart of London

Maxim developed and crafted his machine gun in a shop just two miles from London Bridge near the banks of the Thames. The shop has long since been torn down and replaced, but a plaque on the wall notes the significance of the location. It was at another London address — his home — where he tested his machine guns in the garden.

Ever the courteous neighbor, he ran ads ahead of his tests in the paper, warning neighbors to keep their windows open during testing to prevent them from shattering. (People didn’t think much about long-term hearing damage in those days.)

With financial backing from Edward Vickers, who had made his money in the railroad and steel industries, Maxim started his own arms company. Both men’s names would be forever linked with machine guns.

An improved version of Maxim’s original design was introduced by Vickers Limited for the British Army in 1912 and became known simply as the Vickers machine gun, or just a “Vickers.” The formidable and reliable machine gun was chambered in .303 British. And proved to be a formidable killing machine in World War I and through World War II.

The Maxim Gun’s Impact on Warfare

That brings up only one aspect of Maxim’s impact on history that Ellis was talking about: The Vickers’ role in the expansion of the British Empire during the late-19th century was significant and was an early demonstration of just how much impact machine guns had on the battlefield.

In 1893, during the First Matabele War in modern-day Zimbabwe, 50 British security guards of the Rhodesian Charter Company (part of the British South Africa Company) brought four Maxims to take on 5,000 Zulu tribesmen.

Vastly outnumbered, this would have been a fool’s errand for the British just a few years earlier. Instead, the British and their Maxim-designed machine guns wiped out 3,000 Zulus in less than 90 minutes — they were outnumbered 100 to 1 and they killed 3,000 men in an hour and a half.

In the opening years of the 20th century, the Russians purchased vast numbers of Maxim guns and used them in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. Hiram noted soon after the conflict ended that “it has been asserted by those who ought to know that more than half of the Japanese killed in the late war were killed with the little Maxim gun.”

The Japanese lost between 47,152 and 47,400 men during the war — of those, between 21,802 and 27,200 died from disease, leaving about 11,500 who died from wounds sustained in battle. The death tallies accrued in the upcoming War to End All Wars would make those numbers seem paltry.

Lagging Tactics and Battlefield Innovation

Warfare would never be the same once the concept of the machine gun was released into the world. Military tactics often advance slower than the technology they use, and the Zulu bloodbath was just the first taste of the bloody journey the world’s armies would take to catch up to machine gun tech.

The British suffered one of their worst days in combat with more than 20,000 killed during the first day of the Battle of Somme on July 1, 1916. Most of the soldiers met their demise at the muzzles of German machine guns.

Infantry troops weren’t the only ones to feel the effects of this new firepower. Early in World War I, cavalry troopers mounted on horses launched full-out offensive attacks against their enemies, who mowed down men and horses alike with their machine guns.

On Aug. 24, 1914, the 9th Lancers and the 4th Dragoon Guards attempted a cavalry charge across a wide-open field at Audregnies. Facing an unbroken German line of rifle, machine gun, and artillery fire, their ranks were absolutely decimated.

The role of the horse in warfare completely changed because of the machine gun and calvary, one of the most important components of ground wars for centuries, was made all but obsolete just like that.

Cavalry troopers were no longer engaged in widespread offensive tactics, and the animals were relegated to beasts of burden that moved artillery and supplies around.

By the time the American Expeditionary Forces arrived late in WWI with their own cavalry, they had incorporated machine guns in an interesting way. These troopers sometimes carried Maxims to their place of attack, dismounted their horses, set up the gun, and engaged the enemy from the ground. The idea was to move quickly and nimbly on horseback and to hit hard from the right spot.

Innovation like that helped Maxim’s gun, and the very concept of a machine gun, take flight. And then it actually took flight.

While Hiram’s experiments in aviation never bore fruit, the link between machine guns and airplanes existed almost from the beginning. While the water-cooled Maxim gun wasn’t going to work with the small planes of the era, aircraft were outfitted with the later Lewis machine gun in World War I to great effect.

The first dogfights that took place in the skies over Europe during that war are now the stuff of legend and the beginning of aerial combat. The Lewis gun came around in 1914 and used an air-cooled design, making it feasible for use in aircraft, and a top-mounted pan magazine.

Armored cars and tanks also benefited greatly from machine guns. Most vehicles were far too small and underpowered to be used in conjunction with artillery pieces, but plenty of these early mechanized vehicles of war were equipped with machine guns. Before long, machine guns were mounted to anything that moved, from trains and ships to submarines and blimps.

Maxim’s Lasting Legacy

If Hiram Maxim had never been born or had never gone to Europe, somebody would have invented a practical full-auto machine gun at some point, and it probably wouldn’t have taken too much longer.

You have to look no further than Hiram’s contemporaries, Isaac N. Lewis and John M. Browning, who were working on designs of their own at the time that both eventually become iconic machine guns in their own right. But Hiram S. Maxim got there first, and doing so while working in Europe, the nexus of world conflict at the time, meant his gun proliferated the concept of the machine gun and what it could do very quickly.

If the Maxim gun hadn’t come along when it did, where it did, there’s a chance WWI, and everything that came with it that shaped the world of today may have played out a little differently.

In his later years, Maxim said he would have preferred to have been remembered more for his other inventions. And he did do some things worth remembering, like starting a lightbulb company in 1878. In fact, his United States Electric Lighting Company was neck-and-neck with Thomas Edison’s efforts to sell practical incandescent electric lamps for a time. In 1880, Maxim patented a method for coating the carbon filaments in light bulbs to make them last longer. One of his employees developed a new heat treating method for the filaments that allowed them to be molded into a variety of shapes, including an “M” for the Maxim filaments. He also helped establish an early electric company in England.

“It will be seen that it is a very creditable thing to invent a killing machine,” he said, “and nothing less than a disgrace to invent an apparatus to prevent human suffering.”

He went on to say that if “it been anything else but a killing machine, very little would have been said about it.”

He was certainly right on the money with that assessment, as very few people know anything else about him.

When Hiram Maxim died on Nov. 24, 1916, the Europeans were doing a bang-up job of “cutting each others’ throats” with machine guns. It’s probably a good thing that he didn’t live long enough to see the full-scale involvement of American troops in World War I, as many of them were cut down by guns bearing his name, and far more by guns influenced by his design.

Read Next: Annie Oakley – A Legend Who taught Thousands of Women to Shoot

Comments