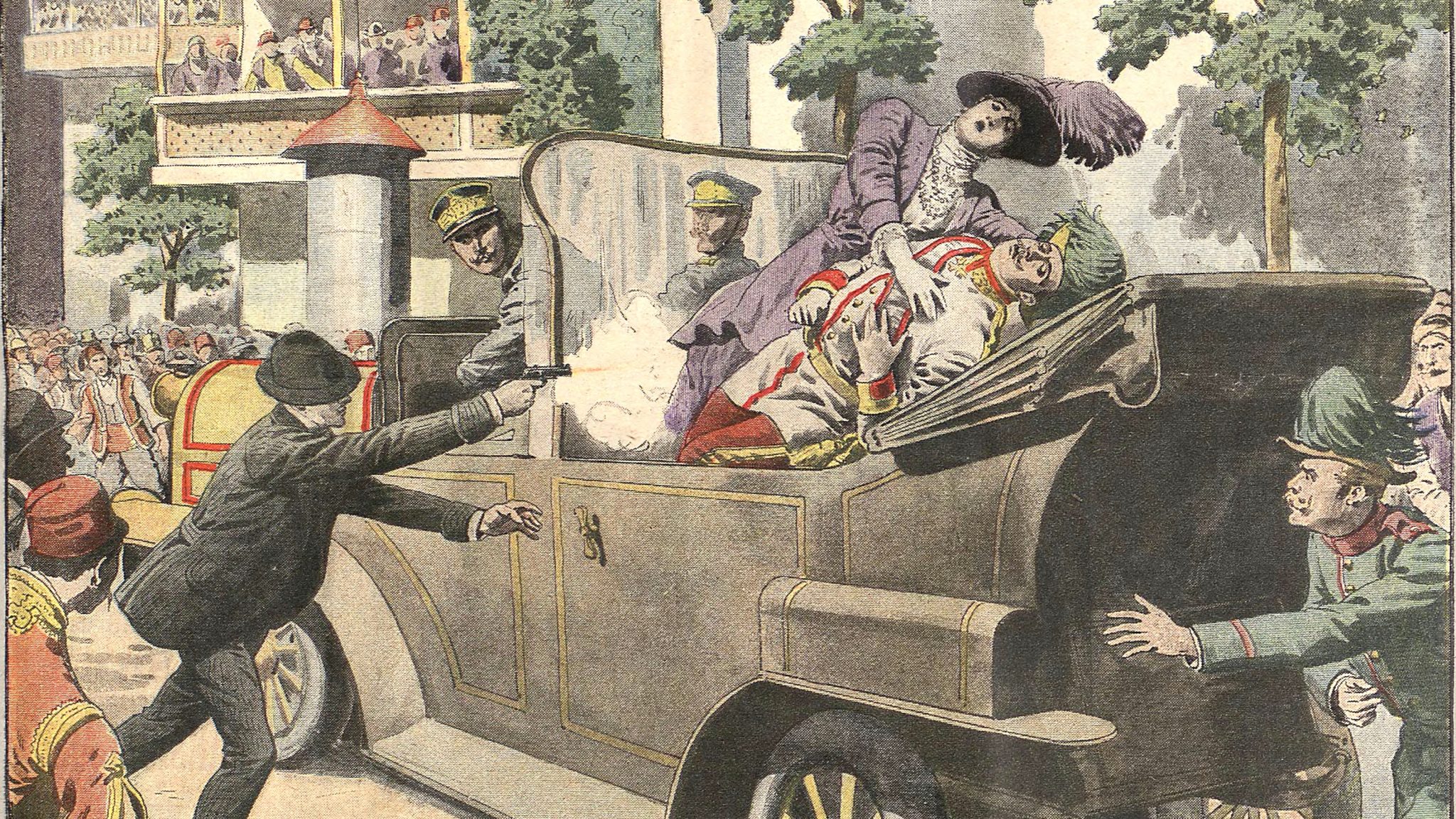

The stench of death loomed. Bombs exploded. Shots echoed along the street. Last words were forced from blood-stained lips, “Sophie dear! Don’t die! Stay alive for our children!” War dawned on the horizon. Gavrilo Princip steered Europe into conflict. A prince lay dead. America would soon join. World War I was born. Sophie would not survive the shooting. She and Archduke Franz Ferdinand lay dead. It was June 28, 1914. Feathers lay limp and blood-stained on the floorboard of their car.

In the years prior to World War I, big feathers and big hats were en vogue. Plume hunters’ eyes were glazed over with dollar signs. The Florida Everglades, home to prized species such as Egrets, Brown Pelicans, and Herons, felt the strength of a hunter’s 10 gauge. Estimates say 90,000 Americans worked in the millinery trade. A course correction would come. It was spearheaded by America’s greatest land and wildlife conservation champions, Theodore Roosevelt and Jay Norwood “Ding” Darling.

“The flock was 1 mile wide, and an estimated 300 miles long. It took 14 hours to pass and it contained — so far as anyone could reckon — 3.5 billion birds.”

Related: Mountain Man Seth Kinman – A Legendary Hunter With Presidential Pals

John James Audubon thought that birds existed in such abundance that no invasion of man would cause harm. Women’s fashion boomed. Ladies’ taste was for feathers. Wisps of Gossamer feathers were highly sought after by the millinery industry. During mating season, these feathers were on prominent display. Adult birds were skinned, the young left to survive. Many would starve to death or become a meal for the opportunistic. Like various previous boom commodities, such as beaver pelts, feathers were big business. New York and London were driving forces for the bloody plume trade.

In 1886, ornithologist Frank Chapman of the American Museum of Natural History conducted two surveys of birds in Manhattan. The survey (simply performed by walking the streets of New York) focused not on flushing birds or flight patterns; instead, these particular studies focused on dead birds, feathers, and the growing effects of plume hunting. Plucked feathers and bird parts dismembered and stuffed served to adorn women’s hats. Wings, feathers, and, sometimes, whole taxidermied birds graced the heads of the fashionable elite.

In the book, The Meaning of Birds, author Simon Barnes recalls a report “of an incident in South Ontario in 1886 when a flock of passenger pigeons flew over. The flock was 1 mile wide and an estimated 300 miles long. It took 14 hours to pass, and it contained — so far as anyone could reckon — 3.5 billion birds.”

Related: 1947 Texas City Disaster – The Deadliest Industrial Accident in US History

Stories about the great flocks of passenger pigeons were told across North America. Skies would grow dark, and temperatures would drop. As the birds roosted for the night, it would be common for one to three inches of dung to cover the forest floors.

“I was suddenly struck with astonishment at a loud rushing roar, succeeded by instant darkness,” the ornithologist Alexander Wilson wrote after he encountered a pigeon flock along the Ohio River in the early 1800s: “I took [it] for a tornado, about to overwhelm the house and everything around in destruction.”

Wilson sat down to watch the flock pass over, and after five hours, he estimated that it had been 240 miles long and held over 2 billion birds. Feathers galore. Such flocks are now gone. The passenger pigeon has been extinct since the early 1900s. James Audubon’s heart would be broken.

Related: How Western Legend Wild Bill Hickok Died in Deadwood

By 1903, opportunistic hunters were being paid $32 per ounce for plumes. That’s $992.74 in 2021 dollars: a hefty sum for a day’s hunt. Bird populations were on the decline as demand for plumes continued to increase. Enter The Hero of San Juan Hill.

In March of that year, President Roosevelt helped form the first reservation for birds at Chapman’s behest: Pelican Island. Chapman came to discover that location was one of the last rookeries for brown pelicans, a prized bird for plume hunters. Paul Kroegel would become the refuge’s first game warden. Before the end of Roosevelt’s presidency, more than 50 bird reservations had been created. Soon, others would champion the cause of wild birds.

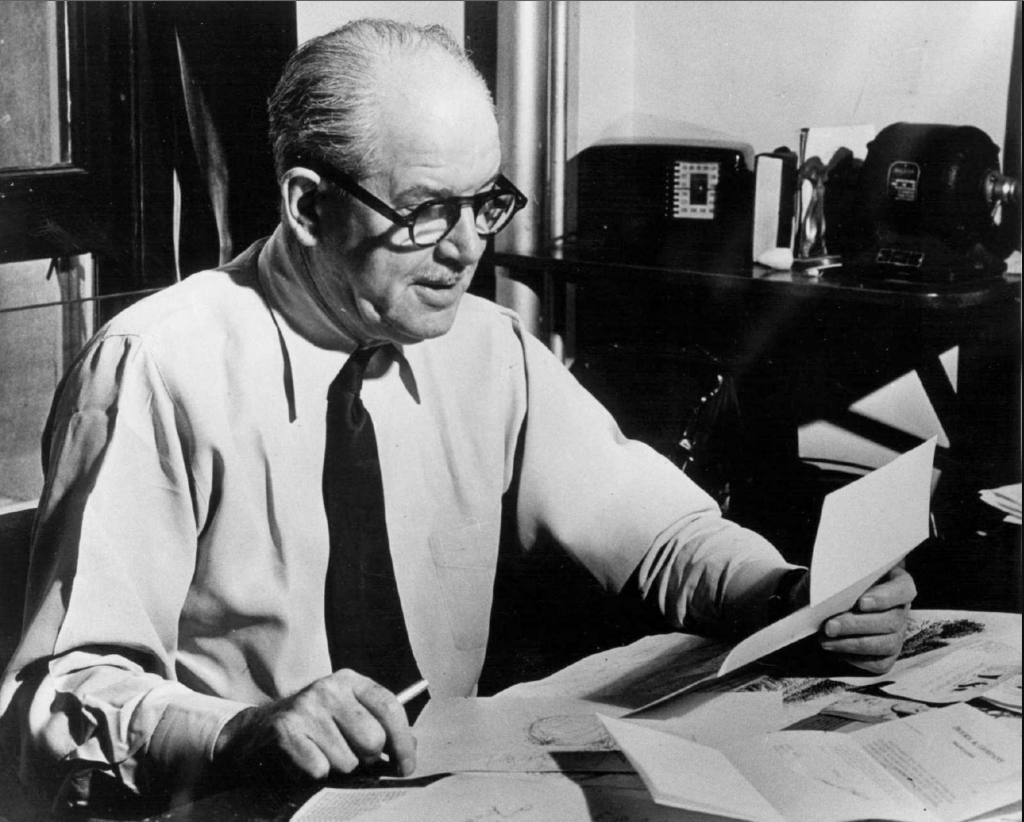

In 1934, another Roosevelt occupied the White House. This time, the president would reach out for help from a man named “Ding.” A beloved and talented man, Darling worked as a cartoonist for the Sioux City Journal and the Des Moines Register for 50 years and won the Pulitzer Prize for cartooning twice in 1923 and 1942. His cartoons were printed across the nation. Franklin Roosevelt would charge Darling with the grand task of heading the US Biological Survey, which led to the creation of the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Its efforts were soon directed toward filling the skies with feathers again.

Related: The Famous Winchester Model 1894 Was Born 127 Years Ago

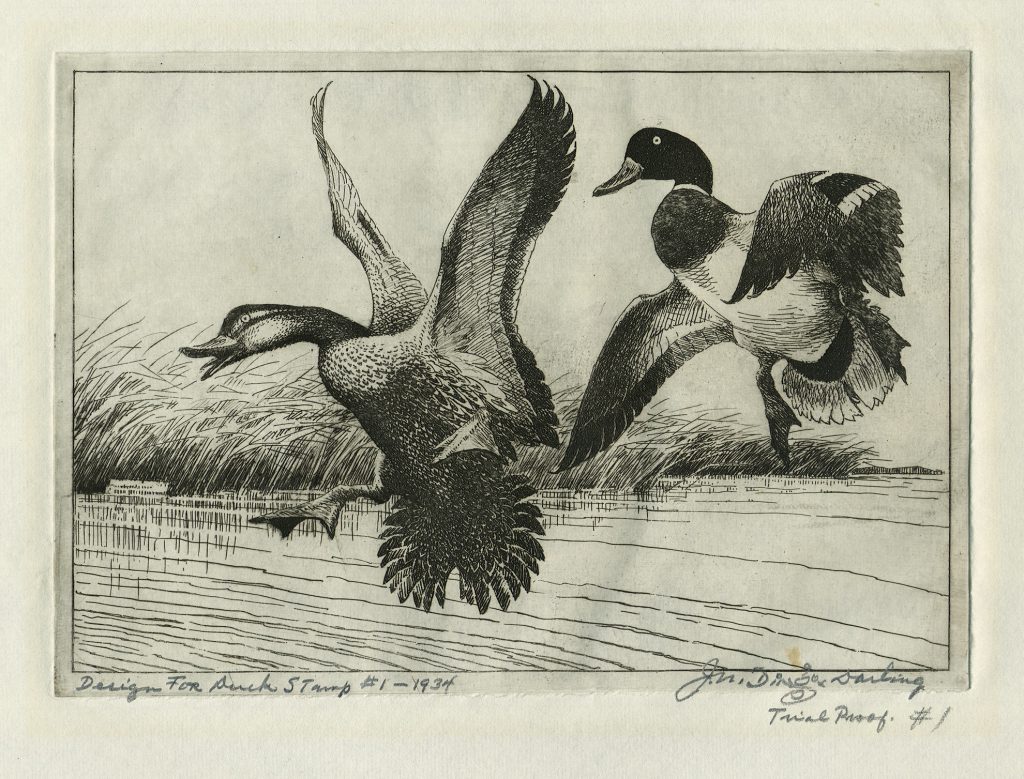

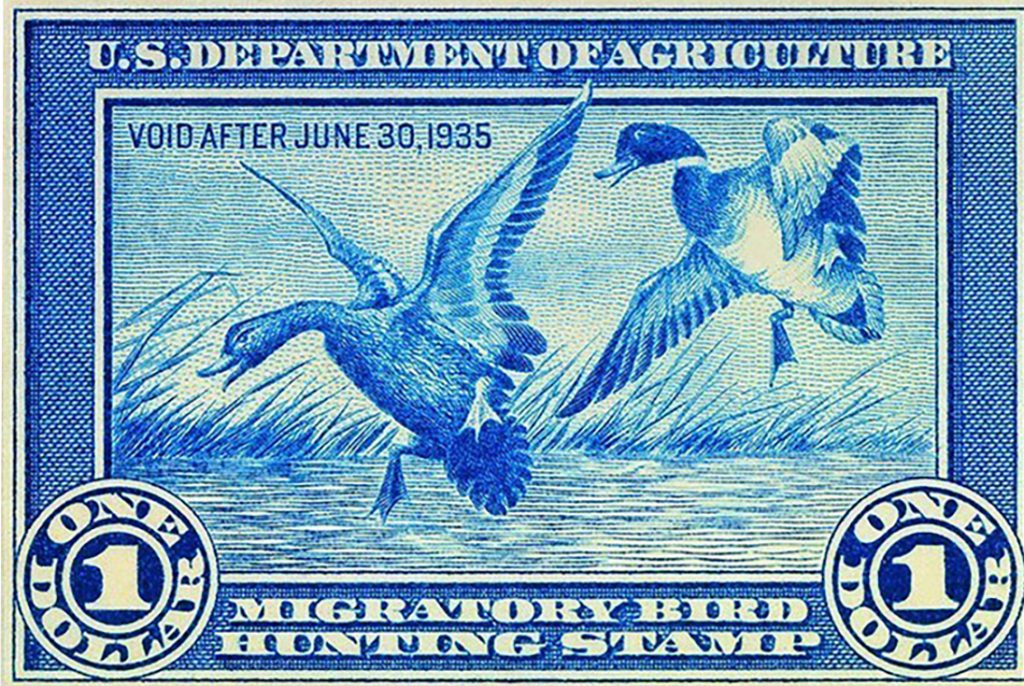

Perhaps the most significant achievement to date for conservation came from the tip of Darling’s pen: the Federal Duck Stamp. The first stamp, which he drew, cost $1.

Since the first duck stamp was sold, over $700 million in funds have been generated by the program, along with 5 million-plus acres of habitat secured for migratory birds. Frank Chapman would be happy.

Each fall, oak trees yield to the coming frost, and hunters set out into rolling vistas and thick timber. Chilled waters slosh over waterfowlers in waders from coast to coast as they await the dawn of a new day. All in the hopes that the sky will be clouded over with flushing feathers and the sounds of soaring fowl. Their hands grasp the cold steel of a shotgun, and their shoulders absorb the recoil. They will smile, for the warmth of stained feathers resting in hand: a privilege almost lost to fashion.

Read Next: Teddy Roosevelt Ran a Suppressor on Three of his Hunting Rifles

Comments