An ordinary man has many limitations, especially in the way of ability and longevity. A legend, however, continues to grow and reshape itself, uncaring of the passage of time. The bigger the legend, the more it evolves as it grows, often becoming wholly unlike the man upon which it is based.

Hemingway, the new three-part documentary from PBS, Lynn Novick, and Ken Burns, attempts to overwrite most of the legend with a more complete picture of the imposing American author, getting closer to the man behind the many words, stories, and legends — and it’s quite successful.

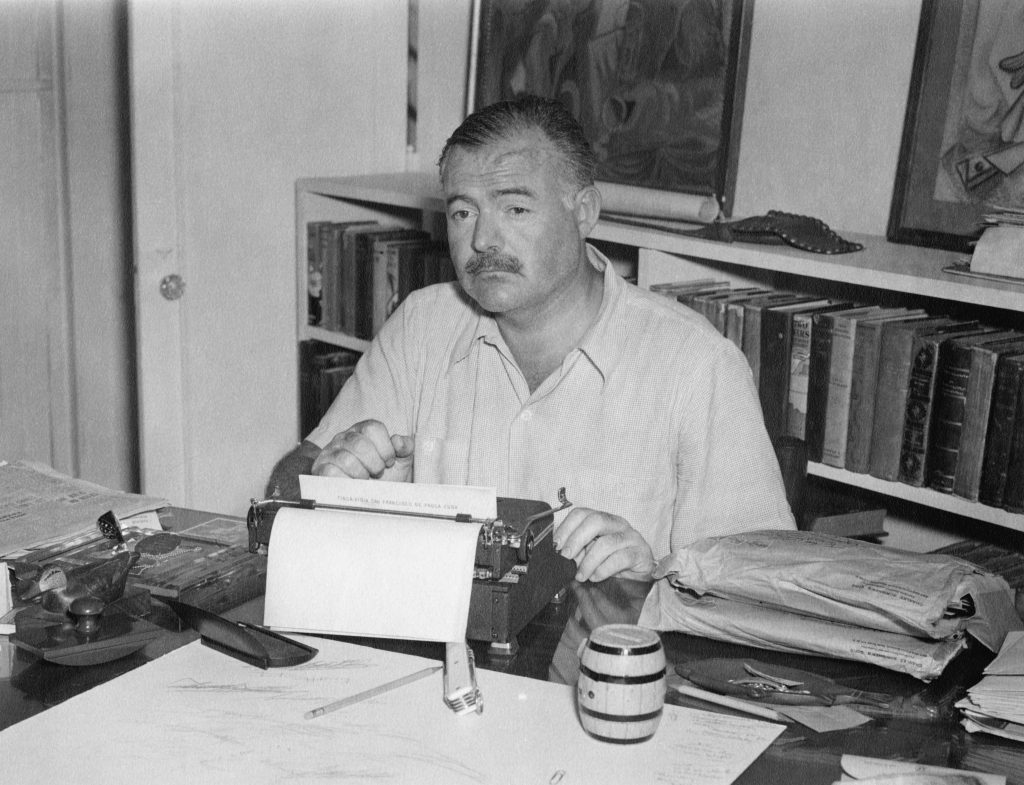

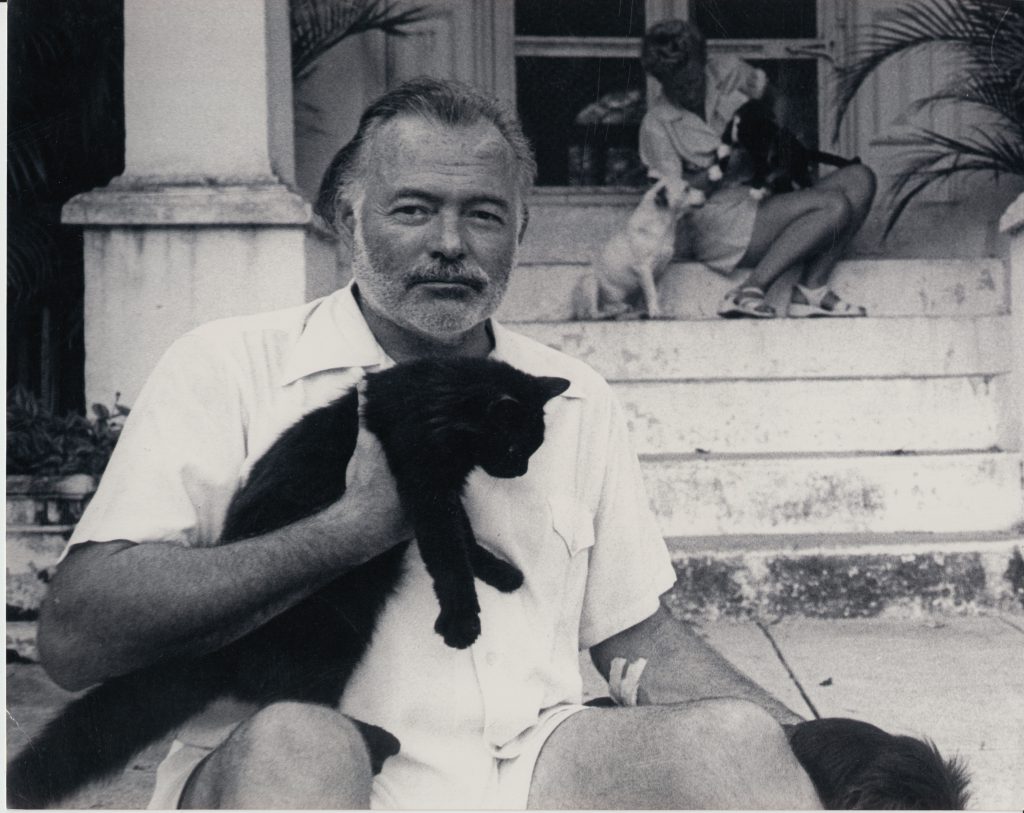

Just hearing Ernest Hemingway’s name conjures visions of an imposing mustached or bearded figure clad in khaki and linen; spending his days hunting dangerous game and his nights draining more cocktails than five other men could; waking the next day to tap out a few pages of genius on a vintage Corona with his morning coffee before attending a bullfight; later taking to the sea to battle an epic, thrashing marlin.

There is some truth to this, but it’s not the whole story.

I had never really given much consideration to who Ernest Hemingway was as an actual person — someone who lived and breathed and brushed his teeth and took shits, in addition to all the truly remarkable things he did. I’ve never read a Hemingway biography, but I didn’t have to in order to get a sense of what people think of him. He was a disciple of no one who created a direct and accessible style all his own, born of the minimalist journalism written in his youth. That’s really American and easy to admire.

When I was in college, he was revered by people who talked about how “the great American novel” had already been written, and who desperately wanted to write just like him.

Eventually, I read a few Hemingway titles — some of his short stories, A Farewell to Arms, and, of course, The Old Man and The Sea. I liked them well enough, and his style appealed to a college kid taking a bunch of journalism classes. To be honest, in my head, I always internally categorized him as a sort of Teddy Roosevelt from a later generation whose profession was writing and drinking instead of politicking.

I spent the summer after graduation in the Castilla y León region of Spain with a good friend of mine who had family there. He took me to a bullfight in a town called Vitigudino. This was in the days before cell phone cameras, so I have no photos or videos — just good, old-fashioned memories of the heat, cheers, awe, and vibrant colors of both the costumes and the blood.

I’m almost glad I never read any of Hemingway’s stories about matadors when I was younger. They may have unnaturally colored a surprisingly moving and remarkable experience. I certainly read them when I came back home, better able to understand his love of Spain and the reality of bullfighting. Still, I had no real concept of the author, and what I thought I knew was still quite off.

Hemingway portrays him as a shark of a man who could not stop swimming for long or bad things would happen. He thrived when adventure and danger were afoot and stress was high, whether taking shrapnel and machine gun fire in the trenches of World War I; hunting for months on safari in Africa; embroiled in the Spanish Civil War; spying on China; or trolling around Cuba during the Second World War, drinking on his boat with two jai alai players on the crew tasked with tossing explosives at German U-boats, if only they could find any.

He managed well in calmer settings when the drinks and the words were flowing, his past adventures fueling his writing, but even then he was constantly traveling and marrying and divorcing. Hemingway grew completely insufferable if he ever got pinned down for too long or felt the doldrums of everyday life. When that happened, consequences were severe, damaging, and unproductive.

If you make a list the wild things the man did in his years, it seems absurd to the point of unbelievability. It’s tough to downplay the scope of Hemingway’s life and experiences — and the documentary certainly doesn’t attempt to do so. Plenty of attention is paid to his various escapades as well as to his writing and literary accomplishments.

With a six-hour run time, the documentary also delves into who Hemingway was on an intimate level, bolstered by narrated personal correspondence to and from those who knew him best and an interview with his son Patrick. They lay bare his feelings on politics, war, suicide, and those he cared for.

The final episode is truly satisfying. It begins with Hemingway’s remarkable exploits in Europe during World War II. Though he’d been involved in at least three wars by that time — and had been grievously wounded as a young man in World War I while working for the Red Cross — in his late 40s, he actually armed himself and regularly fought alongside Allied troops against the Nazis during his time in theater, regardless of rules about war correspondents being noncombatants.

The second half provides remarkable insight into the depression that ultimately ended Hemingway’s life by suicide. Little-known fact: The man sustained more concussions in his life than most NFL quarterbacks do.

He survived two plane crashes in as many weeks during World War II, receiving significant head injuries both times. These capped off a number of severe concussions he’d received earlier in his life from various car accidents and mortar shells, each seeming to take more out of him, physically and mentally — he was suffering from what would likely be diagnosed today as post-traumatic stress. In his later years, it drove him deeper into despair and drink, depression he called “the black ass.”

This isn’t the rundown of Hemingway that you’d get in a high school lit class, or even a college course that inevitably devolves into at least several hours of discussion about his potential latent homosexuality or how he liked his daiquiris. However, the documentary revels in Hemingway’s fishing exploits, it spends precious little time talking about his hunting, and there’s a bit of laughable pearl clutching about his first African safari. One of the writers interviewed thinks it’s a paradox that someone who has been to war could possibly enjoy hunting — because of the killing.

All in all, this documentary is a solid snapshot of who he was as a real person. He was flawed and bad at relationships, a word-slinging genius with an adventurous, tumultuous spirit and a gang of demons trailing after him at all times. He lived the life of 10 men, at least, but in the end, he felt completely alone.

As Hemingway wrote in a letter that was read in the series, “I would rather have one honest enemy, than all the friends I have known.”

Hemingway is divided into three 2-hour episodes and premieres tonight on PBS.

Read Next: Blood Brothers: Theodore Roosevelt and Frederick Selous

Comments