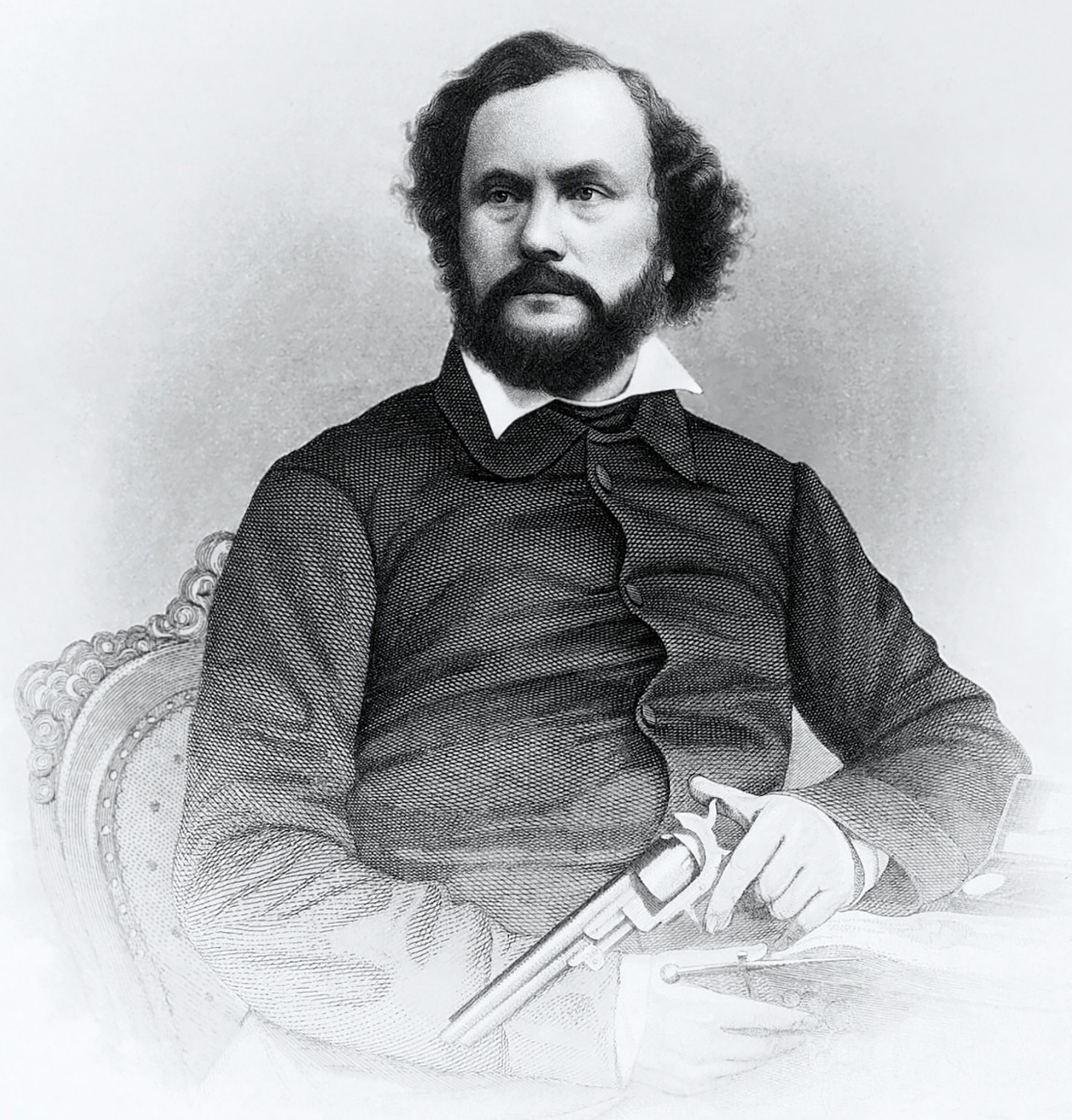

On Jan. 10, 1862, Samuel Colt passed away at his home in Hartford, Connecticut. He was one of the wealthiest men in America, with an estimated worth of $15 million ($413 million today). Death cares little about money, though. Colt died at the relatively young age of 47 from an unremarkable cause: complications of gout.

Colt had a larger-than-life personality, and his name was known in every corner of the globe, which meant a lot more back when word traveled at the speed of ships and horses. And yet, for the people working at his state-of-the-art factory in Hartford, Jan. 10 was just another day. There were guns to be made and orders to be filled.

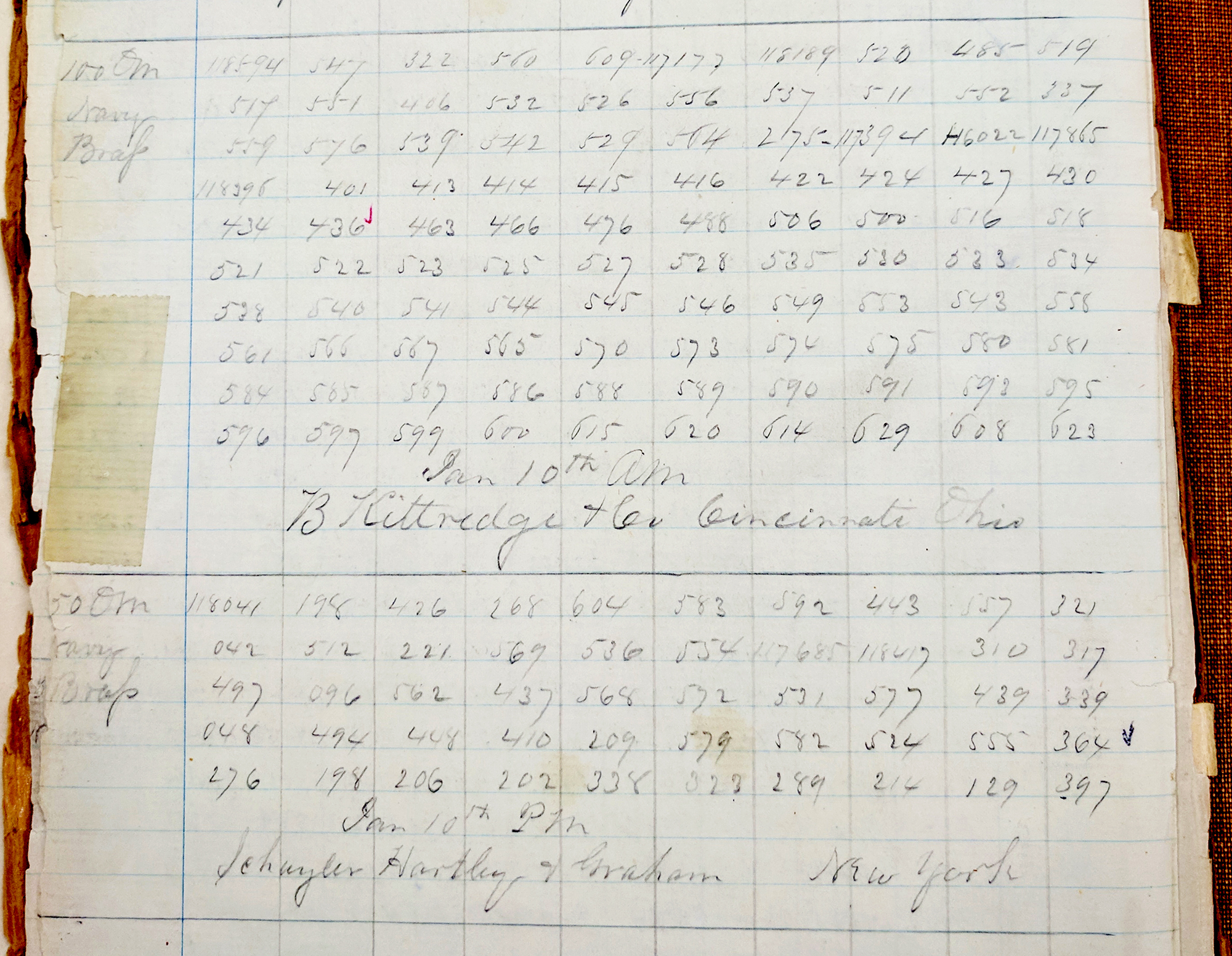

On that day, surviving factory records indicate they filled an order for 100 Colt Navy revolvers in the morning, destined for B. Kittredge & Co. in Cincinnati, Ohio. That afternoon another 50 of the same model went to New York’s Schuyler, Hartley & Graham.

There’s no mention of the date’s significance. There isn’t even a brief side note in the ledger’s margins mentioning the loss of the boss, an industry giant who had pulled himself out of indentured poverty as a child.

Fun With Explosions and Nitrous Oxide

When Colt was a teenager, he had already shown an interest in things that go bang. While he wasn’t yet interested in guns, he was fascinated by explosives and pyrotechnics.

Breaking into the arms industry is not easy or inexpensive, today or 190 years ago. He carved his first 3D model of a repeating firearm with a revolving cylinder out of wood as a young man while working as a sailor. But it would take capital to make Sam’s dream of inventing a working version of the gun a reality. Luckily, he was no stranger to unconventional ways of making money.

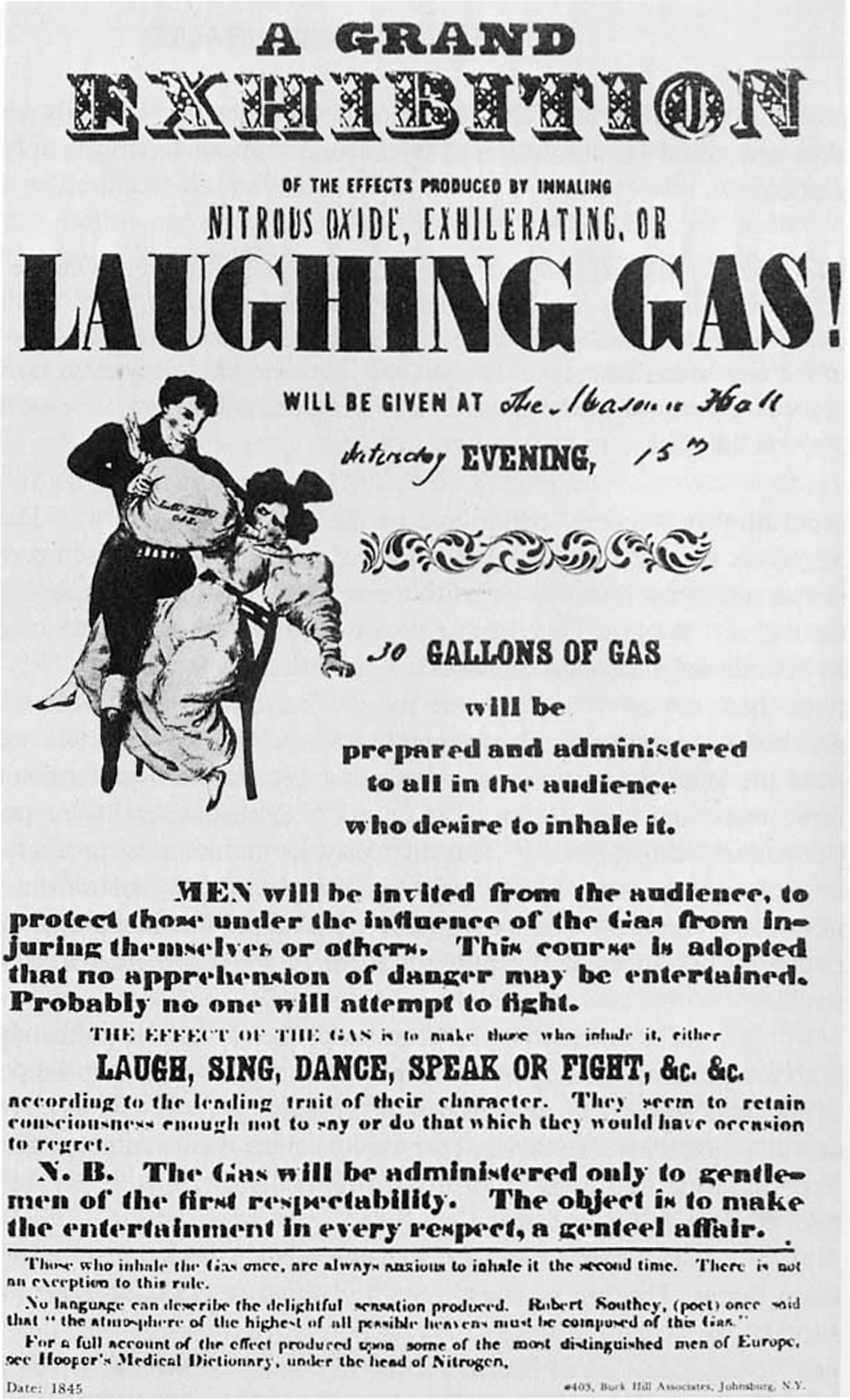

In the 1830s, he billed himself as “Dr. Coult of New York, London and Calcutta” in newspaper ads for exhibitions on the effects of nitrous oxide or laughing gas. He traveled the country as a “practiced chemist,” and often used nitrous demonstrations as a way to raise money for the development of his firearms.

The inventive re-spelling of his last name, the not-altogether-truthful claim of international notoriety, and the outright false claim of being a real chemist were some of the elements of Colt’s first carefully crafted public persona.

The hustle worked okay, but not well enough. There was still plenty of hard work ahead for Colt before fame and fortune would be attainable, and Colt made his first real money putting his inventor’s mind to work on projects unrelated to firearms.

He spent a number of years working under the direction of the Secretary of War on new detonation technology for naval mines, including new types of waterproof cable. He ran a sheet metal rolling mill for a while and even had a nail-making factory at one point. None of those ventures ever fully panned out, but Colt was undeterred.

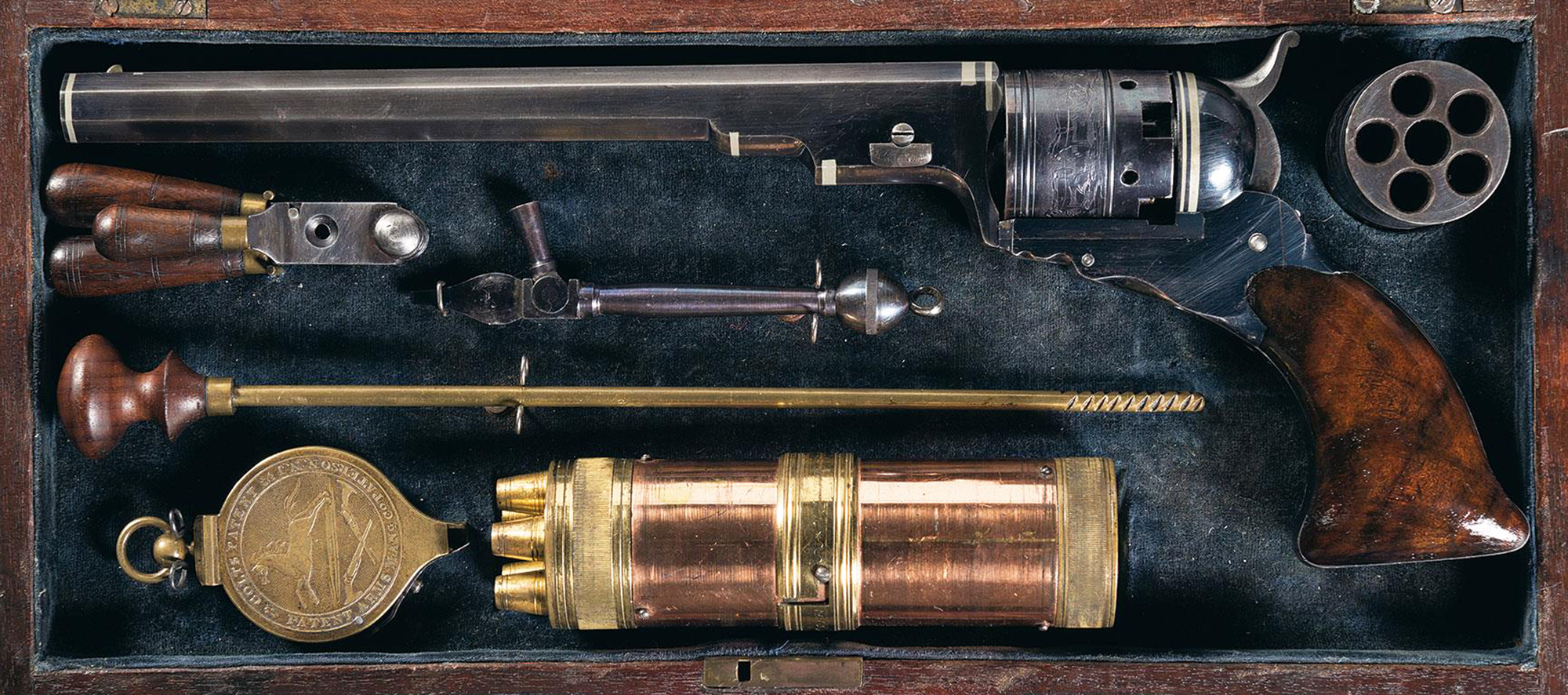

In 1836, he had finally completed what he set out to do and received a patent for a revolving firearm. This five-shot handgun was known as the “Paterson revolver,” named after the location of Colt’s factory in Paterson, New Jersey. (His more famous Colt Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Company factory in Connecticut would come later.) The patent garnered some outside financial backing, which meant Sam was ready to kick things into high gear and shake up the arms industry.

Unfortunately, what Colt thought was his big break turned out to be a disappointment in the end. Sure, his gun was new and cutting edge, but he needed a large government contract to make any money and to ensure that both he and his creation would be more than just a flash in the pan.

The spark didn’t catch in the way he’d hoped. The Paterson proved too fragile for heavy field use and the large military contract he dreamed of never materialized. Overall sales dropped, and Colt was forced to close the doors of his New Jersey factory just a few years after it opened. Never one to give up, though, Colt kept pushing forward.

RELATED – Hiram Maxim: The Right Place, Right Time, Right Gun to Change History

A Visit From Capt. Walker

When Captain Samuel H. Walker of the Texas Rangers came calling in the 1840s and ultimately ordered 1,000 pistols, Colt finally got his big break. Walker had used Colt’s Paterson revolver while fighting against the Seminoles in Florida and saw potential in the gun’s design. Walker wanted Colt to make a list of revisions to the gun and put it back into production, but Colt had no capital to make it happen. This began the development of a long, drawn-out, and complex relationship between Sam Colt, Eli Whitney Jr., Sam Walker, and countless military and government officials over the next few years.

When all the wrangling was through and everything was in place, Sam Colt produced the .44-caliber Colt Walker revolver in 1847. Today it’s one of the most legendary, sought-after, and expensive models in all of the gun collecting world. Creating the Walker taught Sam some valuable lessons. He learned how to properly wheel and deal with the government, to tell (a lot) of white lies and half-truths, and fake it until you make it.

The rise of the Walker revolver put Sam on surer footing, and he started working on expanding his line of pistols. The Dragoon series of revolvers followed, which were basically improved versions of the Walker. Then came the 1849 Pocket, 1851 Navy, 1860 Army, 1861 Navy, and others.

Much of his success was due to his willingness to embrace the “American Method of Manufacturing,” which is a fancy way of describing what is, essentially, an assembly line. The use of interchangeable parts allowed Colt’s workers to produce better guns faster than anyone had before because each part was the same as the last. Plus, parts from different production batches made at different times could be assembled into a complete firearm, which also meant Colt could sell what were practically drop-in replacement parts for his firearms. It’s the same concept Henry Ford would apply to the auto industry — a half-century later.

In his mid-40s, Sam had truly arrived. He was a resounding success by every personal measure — except one. The descendant of a major in the Continental Army, Sam had not carried on his family’s military legacy, something to which he had always aspired.

Thanks to his fame and fortune, this shortcoming was soon remedied. Colt was commissioned as a colonel on May 16, 1861, and was set to command the 1st Regiment Colt’s Revolving Rifles of Connecticut.

The regiment never actually became a thing, and he was discharged a month later on June 20. Still, Sam had succeeded in getting a military commission, and with the US embroiled in the Civil War, business was very good for Colt.

Despite his exceptionally short tenure as a military man, Colt likely saw the commission as a legitimization of his previously self-appointed title of colonel that he had placed on many of the presentation arms he gifted to people all over the world. But he didn’t get to enjoy any of it for long, nor did he get to see the greatest achievements of the company he established.

RELATED – Horace Smith, Half of Smith & Wesson, Was Born 213 Years Ago

That Gout’ll Get Ya

After his untimely demise at 47 from gout complications, the company that bore his name continued to thrive. In fact, two of the company’s most successful, and now-iconic, guns — the Single Action Army revolver and the Model 1873 lever-action rifle — debuted more than a decade after his death.

The fact that his company created the “Guns That Won the West” years after he was dead and gone is a testament to the solid footing Samuel Colt created for his business.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter that the Colt factory ledgers make no mention of his passing. What really matters, and is a true mark of success for the Colt brand (despite the company’s business problems and sale in the past three decades), is that we are still, some 160 years after his passing, talking about Sam Colt and the guns he created. That is, by far, a much better legacy than a hastily scrawled obituary in a factory ledger.

READ NEXT – Oliver Winchester and Sam Colt: Innovators and Lousy Gunmakers

Joseph Houseman says

“complications of gout” is a polite way of saying “he died of syphilis”