On a bench along the Wisconsin River sat Aldo Leopold, a revered conservationist and outspoken advocate for wildlife science. On any given day in the late 1930s, Leopold, although in poor health, would venture to his writing haven he and his family referred to as “the Shack” to scribble his ideas down on paper. Those ideas were expressed in the essay titled “Land Ethics,” which was published in 1949, a year after his death, in his now-famous book A Sand County Almanac.

The book sold more than 2 million copies and cemented Leopold as one of the most influential conservation thinkers of the 20th century. “When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect,” he wrote. “We can only be ethical in relation to something we can see, understand, feel, love, or otherwise have faith in.”

Leopold produced more than 500 articles, essays, and reports about forestry, wildlife management, conservation biology, sustainable agriculture, restoration ecology, private land management, environmental history, and ethics in his lifetime. To put it mildly, he had a masterful presence in a variety of outdoor fields and a particular ability to present complex scientific ideas to a general audience, something his writings achieve to this day.

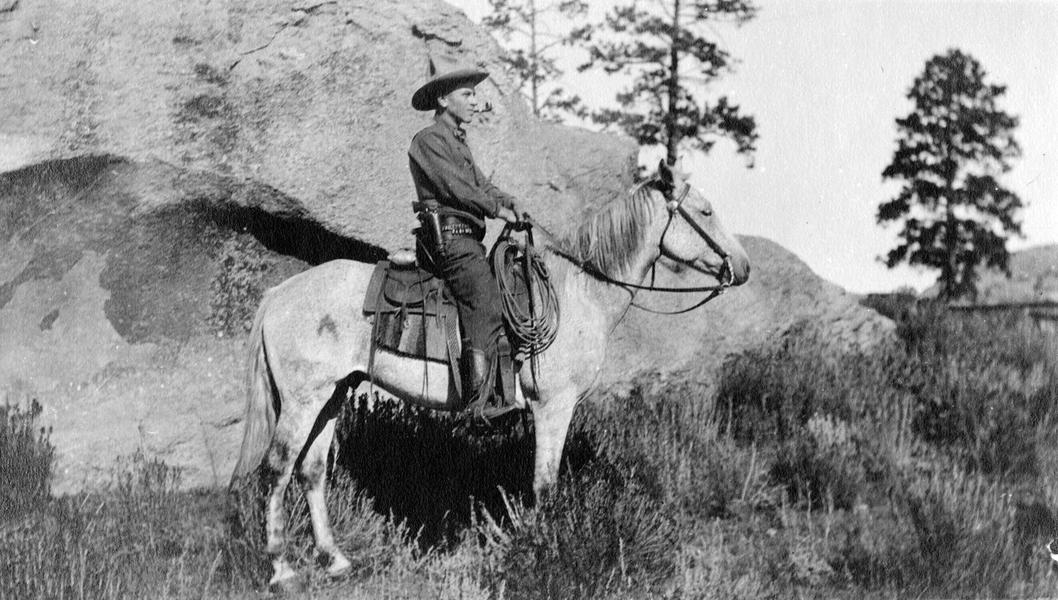

Aldo Leopold was born and raised in Burlington, Iowa. As a youth he gravitated toward the wilderness, and he joined the newly established US Forest Service (USFS) in Arizona following his graduation from Yale Forest School in 1909. Seen above, Leopold patrolled on horseback in the Carson National Forest in New Mexico.

“When the pioneer hewed a path for progress through the American wilderness, there was bred into the American people the idea that civilization and forests were two mutually exclusive propositions. … A stump was our symbol of progress,” he wrote in 1918 while he worked at the Gila National Forest. “We have since learned, with some pains, that extensive forests are not only compatible with civilization, but absolutely essential to its highest development.”

In 1922, he developed a proposal to manage the Gila National Forest, making it the country’s first official wilderness area. Throughout his 20-year career in the USFS, his experience molded his future ideas on conservation.

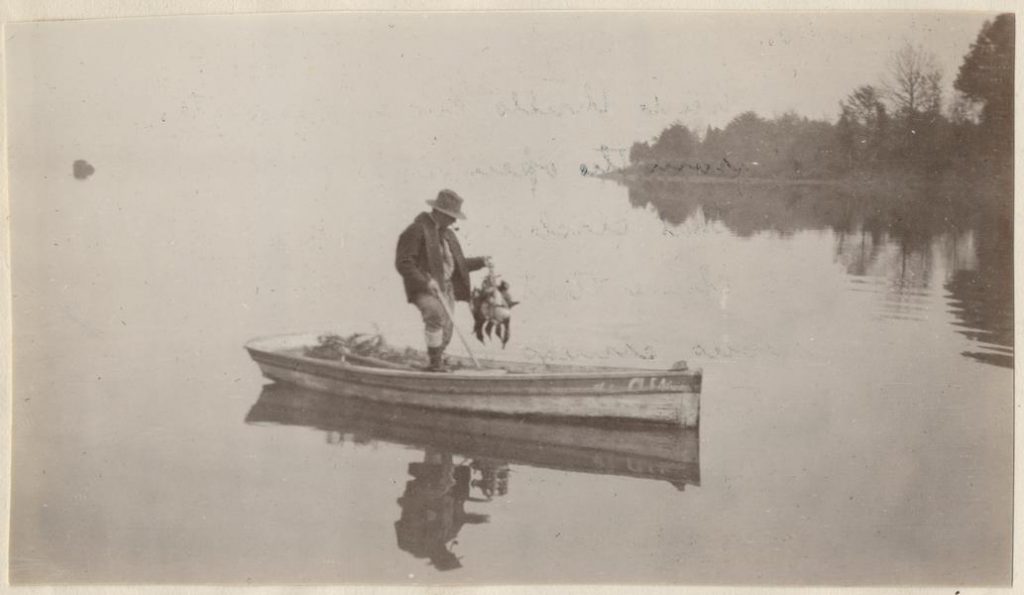

“My earliest impressions of wildlife and its pursuit retain a vivid sharpness of form, color, and atmosphere that half a century of professional wildlife experience has failed to obliterate or to improve upon,” Leopold wrote in his essay “Red Legs Kicking,” describing the first time he hunted a duck as a boy. “I could draw a map today of each clump of red bunchberry and each blue aster that adorned the mossy spot where he lay, my partridge on the wing. I suspect my present affection for bunchberries and asters date from that moment.”

Those childhood impressions strengthened his resolve when he considered the consequences of creating and destroying healthy ecosystems.

Leopold was one of 40 people who advocated for a bowhunting season in Wisconsin. And hunting wasn’t only a father and son affair. Leopold’s wife, Estella, was an avid bowhunter too, a fact that newspapers in Wisconsin weren’t shy to publish.

In 1924, Leopold investigated the ecology and philosophy of conservation, which culminated in his first textbook in the field of wildlife management, published in 1933. In the photo above, Leopold is in the back row, farthest to the left, pictured with his family and their beloved dog Gus.

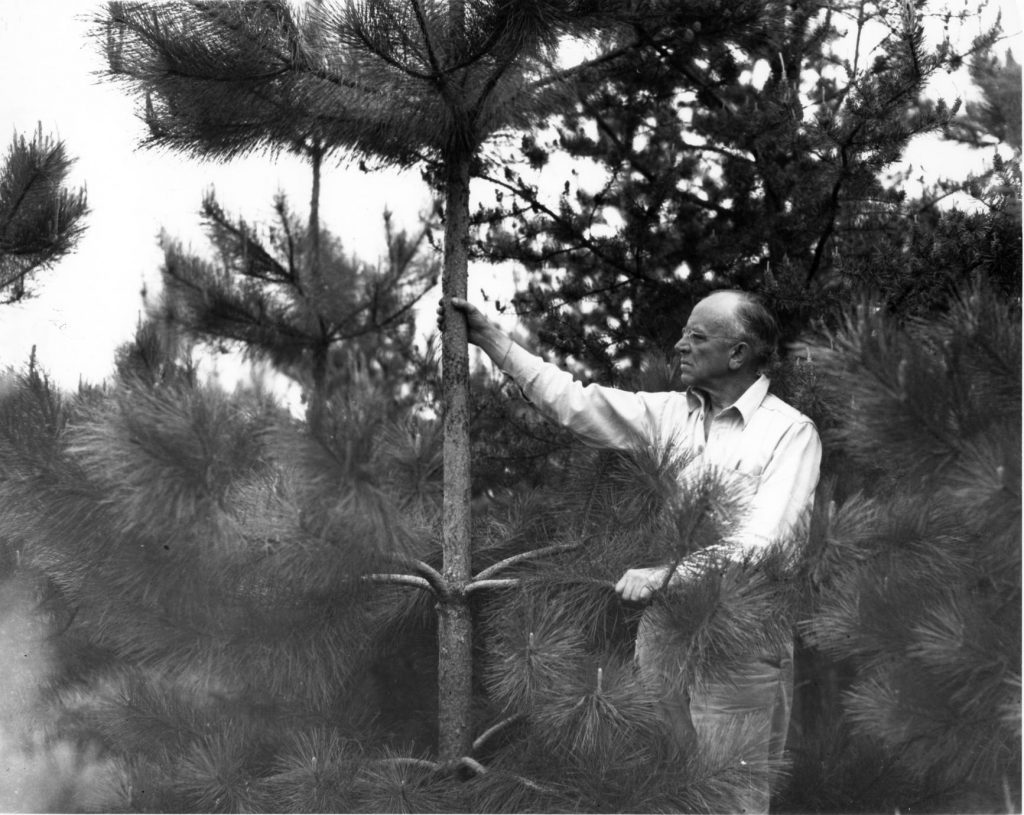

In 1935, the Leopolds purchased worn-out farmland and spent the subsequent years planting hundreds of trees to bring it to life. For years the trees fell victim to severe drought, and Leopold documented the changes in flora and fauna along the way. In the above photo taken in 1946, Leopold examines red pines on his property. He had never been one to give up, and the land today has a restored base of pines, hardwoods, and prairies. Two years after that photo was taken, Leopold suffered a fatal heart attack while helping a neighbor suppress a fire.

Read Next: Monarch Butterflies, on Brink of Extinction, Garner Congressional Attention

Comments