After decades of decline and neglect, the 16-gauge is getting a lot of attention right now; it’s the in gauge. I recently told a friend who is a double-gun expert that I was trying to talk myself into a 16, but I couldn’t find a reason. Stuck in a shrinking niche between lightweight 12s on one side and 3-inch 20 gauges on the other, there isn’t much of anything a 16-gauge shotgun can do for me that the guns I already owned couldn’t do better, I told him.

After acknowledging that yes, I was correct, my friend was left with only one argument, and it’s the one that seems to be winning these days: “But . . . but, 16s are cool!”

And that they absolutely are. I remember the first 16 I ever saw — a beautiful Spanish sidelock in the hands of a man who had it custom-made while he was working overseas. His safari shirt was pressed, his eyes were steely, and he rarely missed. After he shot a dove, he’d open the gun and a slim, elegant, smoking purple hull would pop out. So yes, I get that part of the 16’s appeal, which is why I wanted so badly to talk myself into one of my own.

Ultimately, I compromised. I skipped the fancy break-action I wanted and found a nice 16-gauge Model 12 pump for a price that didn’t wreck my budget. I don’t shoot it much, but it’s nice to know it’s there in the gun cabinet.

If you want a smallbore that’s a little different, the 16 makes a fine choice. It used to be called “Queen of the Uplands,” and a good 16-gauge, built on a true 16-gauge frame and loaded with 1 ounce or 1 1/8 ounces of lead shot, makes a wonderful, easy-carrying upland gun.

The current trend to smallbore waterfowl hunting (which I also don’t get, but that’s me) means plenty of people are taking 16s to the blind. Loaded with an ounce of bismuth or 15-16 ounces of steel, they are fine over-decoy guns, too. You can do a lot of hunting with a 16-gauge and never feel over- or under-gunned.

But you won’t find 16s in registered clay target competitions, and you rarely see them in informal target shooting. Nor is there much available in the way of 16-gauge turkey ammo. Shooting a 16 means you’re choosing tradition over practicality. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that if that makes hunting and shooting fun for you. None of us does this for a living or to survive, after all.

RELATED – The ‘Freakin’ 12-Gauge’: The Only Gauge You Really Need

16-Gauge Specs

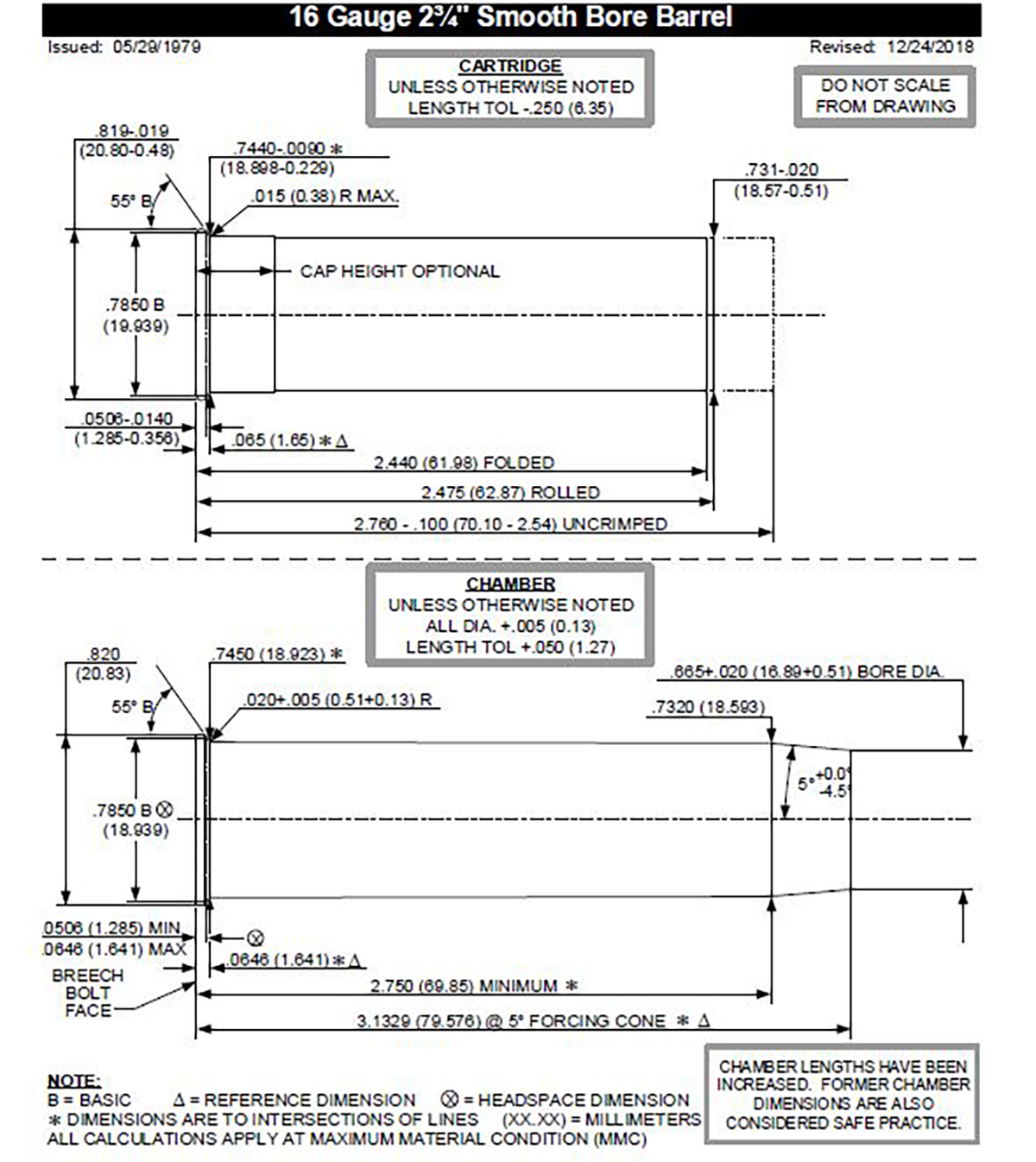

Sixteen one-ounce lead balls measure .662 inches, and that is where the 66-caliber 16-gauge gets its name. Modern 16s come in 2 3/4-inch chambering only, while in the past 2 9/16-inch and shorter shells were also popular. The standard 16-gauge loading is 1 ounce to 1 1/8-ounces of lead, an ounce to 1 1/8 ounces of bismuth, and 15/16 ounces of steel.

A 3-inch 20-gauge, it should be noted here, holds a full ounce of steel. There are full-bore 16-gauge slugs and loads of #1 buckshot, but in general, there is not a wide selection of 16-gauge ammunition. Thanks to the current interest in 16s, it’s not scarce, but it is limited.

Sixteen-gauge ammunition often patterns quite efficiently if you limit shot charges to an ounce or a little more. As a rule, larger bores damage fewer pellets than smaller bores, and a 16 is likely to slightly outperform a 20-gauge on the pattern board. That edge in patterning is one reason hunters used to say that the 16 “hit like a 12, carried like a 20.”

There are more 16-gauge guns available now than there have been in a while; there are plenty on the used market as well. Before you buy, be aware that there are two kinds of 16s: 16s built on 16-gauge frames, which are worth buying, and 16s that are nothing more than 16-gauge barrels on 12 gauge frames, which you should avoid.

A true 16 will be slim, light, and a joy to carry and shoot. A 16 on a 12-gauge frame is just an underpowered 12-gauge: Remington 1100 and 870s come to mind as 16s to avoid for this reason.

RELATED – What’s Behind the Supposed ‘Magic’ of the 28-Gauge

16-Gauge History

Fowling pieces with 16-gauge barrels were quite popular in the muzzleloader-only days before shotshells. When breech-loading cartridge guns came along in the 1860s, Continental hunters — Germans in particular — took to the 16-gauge, which is why you will see a lot of 16-gauge German double guns. It also made a good shotgun gauge for combination guns. The 16’s trimmer barrels and frame meant you could put a pair of shotgun barrels over a single center-fire barrel and have a three-barreled “drilling” that was ready for any game.

The 16 became popular in the United States through the first half of the 20th century. Our 12-gauges were heavier than European 12s, so a 16, which carried easily and fired an ounce or more of shot, made for a light and logical choice as an upland gun in the US.

Many 16s of the pre-WWII era have 29/16-inch chambers. American shotshell lengths were standardized in the 1920s, in part due to the growth in the popularity of skeet shooting.

Sixteen-gauge skeet guns did exist, but eventually, the game was divided into 12, 20, 28, and .410 events. You could shoot a 16 in 12-gauge events, and some did (and won), but by and large serious shooters forgot about the 16 and shot 12s. Being excluded from skeet hurt the 16, but what really cut into 16-gauge sales was the 3-inch 20-gauge, which appeared in the 1950s.

The 16’s niche between the 12 and the 20 was a lot narrower all of a sudden as the new magnum 20-gauge shells held as much shot as a 16-gauge could. Gunwriters, who love to write about new things, made a huge deal over the 3-inch 20-gauge, touting it as an all-purpose gun, much to the 16’s detriment.

The coming of nontoxic shot requirements dealt the 16 another blow. It actually held less steel shot than a 3-inch 20. When I first hunted in Arkansas in the mid-1980s, my hosts all shot 16s and lead. When I hunted with the same people a few years later, lead was no longer legal, and they’d all switched to 12-gauges.

One of them had to hang up the Browning Sweet 16 (aka the A5 Sweet Sixteen), with which he’d shot thousands of ducks and quail. The scaled-down, lightened version of the Browning Auto 5 was a favorite among upland hunters.

The 16 hung on, kept alive by a dedicated cult, and now, 16s are in again. When Browning introduced its new A5 (not the same gun, but a Benelli-like inertia gun with a humpbacked profile), they made the brilliant decision to make a Sweet 16 version. That gun, almost by itself, sparked a 16-gauge revival. The last few years have seen a nice uptick in new guns and ammo for the 16.

RELATED – Shotgun Shells: The Most Important Developments of the Past 10 Years

Shotguns Available Today

Sweet 16 A5

The gun that singlehandedly kick-started the 16-gauge comeback, the A5 Sweet 16 is a very lightweight (under 6 pounds) inertia-operated semiauto. It has Browning’s effective Inflex recoil pad and comes in a variety of finishes, from the classic, round-knob Lightning with gloss walnut to the Cerakote-and-camo Wicked Wing for those who would like to take their 16 to the duck blind. MSRP: Starting at $1,869.

Browning Citori 16 Feather

Another lightweight 16 from Browning, the Citori Feather has an alloy frame that shaves its weight down to a little over six pounds. The gun has a straight grip and schnabel forend for fast pointing and classic good looks, along with a silvered, engraved receiver. It comes with either 26- or 28-inch barrels. MSRP: $2,469.

Franchi Instinct SL

Another alloy-framed 16-gauge O/U, the Instinct SL likewise weighs around 6 pounds. It has an unadorned, silvered receiver, a rounded Prince of Wales grip, and vented ribs between the barrels. It comes with extended choke tubes. It’s a light gun and easy to carry, but unlike some light guns, it’s also well-balanced and easy to shoot. My frequent pheasant-hunting partner shoots one, and he shoots it so well I don’t know why he doesn’t leave all his other guns home and stick with the Franchi. MSRP: $1,779.

Fausti Dea SLX

Italian maker Fausti is overhauling its American lineup, and the very nice Dea SLX is the Fausti gun that seems to strike a chord with hunters over here. It’s a classic straight English-gripped double gun (although purists would prefer double triggers), and it has engraved side plates and oil-finished AAA walnut. The Dea comes in every bore size from 12 to .410, each built on its own scaled frame, so the 16 is a dandy lightweight. But remember, no one ever said elegance is cheap. MSRP: $6,040.

RELATED – Where Have All the Side-By-Side Shotguns Gone?

16-Gauge Ammo

Currently, there are plenty of 16-gauge ammo offerings for upland and waterfowl hunters. Federal makes its Upland Pheasants Forever High Velocity load of 11/8 ounces of copper-plated shot at 1425 fps in 4-, 5-, and 6-shot. A pheasant won’t know the difference between this load and a 12-gauge pheasant load.

Boss Shotshells goes all-in on the 16-gauge, loading its copper-plated bismuth in 1-ounce 16-gauge loads at 1350 fps in 3-, 4-, 5-, 6-, and 7-shot as well as a 3/5 blend. Boss keeps its prices down by only selling direct to consumers.

Browning, through its partnership with Winchester, produces ammo for their Sweet 16 and other guns. There’s a BXD Upland, containing 11/8 ounces of nickel-plated shot at 1295 fps in a long-range wad. If you have an old, short-chambered 16, RST makes a 2 1/2-inch, 7/8 ounce Falcon Lite and a 3/4-ounce Falcon UltraLite in shot sizes 5-9 — but as a relatively small ammo company, RST is currently struggling to find components.

The Future

The 16 is in vogue for the moment, and it will never go away entirely. However, failing some innovation like a 3-inch chamber (as was recently done to the 28-gauge), enthusiasm for the 16 will probably wane back to its usual low level. And, that’s okay.

There isn’t a lot a 16 can do that a lightweight 12-gauge or 3-inch 20 doesn’t do better, but if you want to find one and shoot it, they are a terrific, effective, classy choice in a hunting gun, and it always will be.

READ NEXT – Is There Still a Reason for the 10-Gauge Shotgun to Exist?

Comments