When it comes to keeping their friends close and their enemies closer, research shows moose in northern Minnesota are seeing a life-saving benefit by co-existing with wolves. On the other hand, beavers in the north woods are becoming a favorite wolf snack, getting snatched as soon as they leave their colony and before they can get to dam building.

The unexpected ways in which the growing wolf population is interacting with these two species have spawned research into the positive and negative effects of the individual predator-prey relationships with some surprising results.

The predators are actually protecting moose from contracting a deadly brain parasite from deer. In the same area, wolves doing what wolves do has resulted in reduced beaver-colony expansion, changing ecological processes like water storage, nutrient cycling, and forest succession.

Wolves and Moose: Unexpected Allies

RELATED – Predator Calling Contests Under Attack From Virginia Lawmaker

Over the past 15 years, 23% of collared moose in northern Minnesota have died of Parelaphostrongylus tenuis, a roundworm parasite contracted from whitetail deer. The parasite is one of the biggest threats to adult moose mortality in the state.

Researchers estimate approximately 25% to 45% of Minnesota moose have become ill or died due to the parasite. Brain worm eggs spread through fecal matter to slugs and snails that moose inadvertently eat along with mouthfuls of plant material.

From 2007 to 2019, researchers from the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine and the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa studied the dynamics of moose-whitetail interaction driving the infection and the impact wolves have on slowing the transmission of the parasite.

The moose population in Minnesota has remained steady at 2,400-4,320 animals for almost a decade. While stable numbers state-wide are positive, northern Minnesota has seen a steady decrease since 2006. There has been no hunting for moose since 2013, when their population crashed from an estimated 9,000 animals. Three Ojibwe bands in Minnesota do permit limited hunts.

RELATED – How ‘Dances With Wolves’ Changed Westerns Forever

The study found that, historically, deer and moose habitat overlapped significantly during spring and summer migrations. These periods are also the time of greatest brain worm transmission risk.

They also discovered that wolf pressure during the spring and summer was linked to greater segregation of deer and moose across habitats — spatial compartmentalization between prey species resulting from a non-lethal predator mechanism.

In other words, wolves are doing their largest meal ticket a solid by keeping deer and moose apart and reducing the opportunity for parasite transmission.

“We often think of wolves as bad news for moose because they kill a lot of calves,” said Tiffany Wolf, a principal investigator in the study. “But this suggests that wolves may provide a protective benefit to adult moose from a parasite-transmission perspective. Because brain worm is such an important cause of adult moose mortality in Minnesota, we can now see that the impact of wolves on moose is a bit more nuanced.”

RELATED – The Current Status of Gray Wolves and Hunting in the US

The Wolf-Beaver Dynamic

The beavers of northern Minnesota are an iconic species responsible for engineering ecologically important wetlands that contribute to the state’s 10,000 lakes.

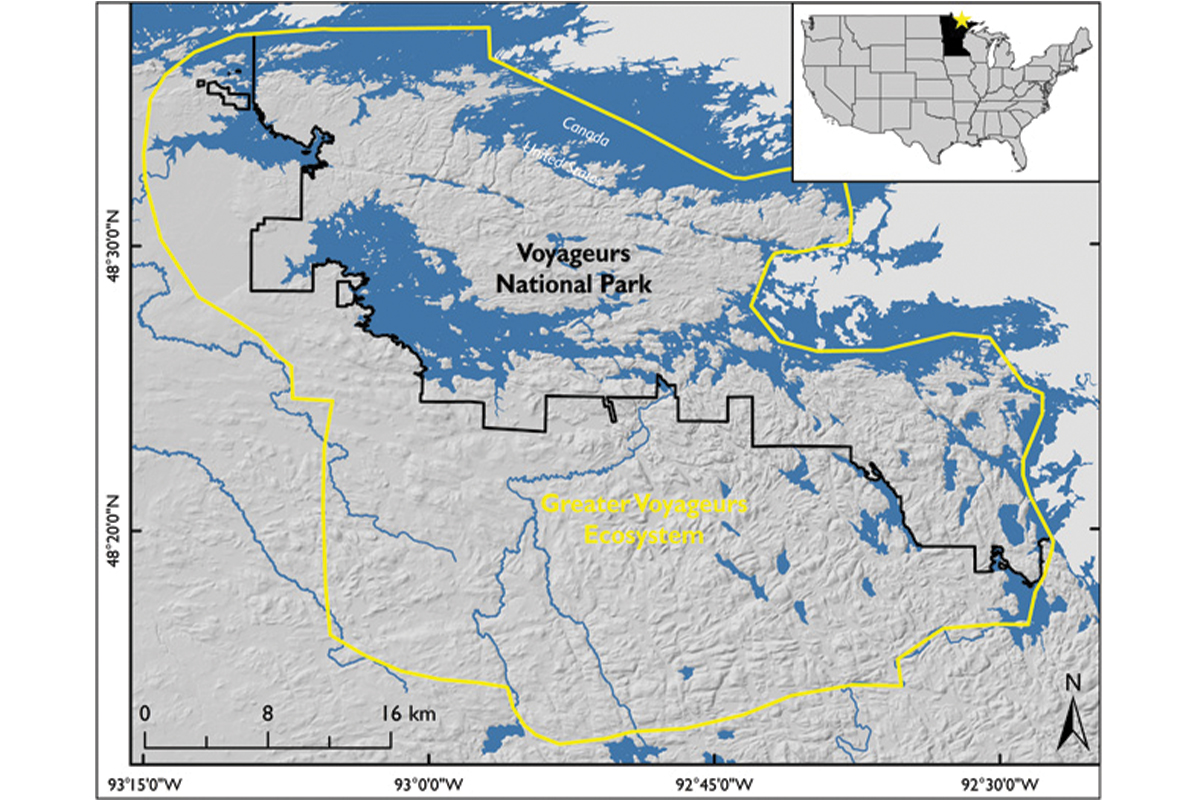

In Voyageurs National Park alone, 13% of the park is covered by the handiwork of the toothy critters — a whopping 7,175 beaver-created impoundments (both occupied and unoccupied) in the park were tallied in 2019.

But since wolves have developed a taste for Wynona’s big brown friend over the last few decades, those wetland expansions are in jeopardy of drying up — or potentially imposing unwanted changes on a wider geographic area.

Yes, whitetails are still the primary prey species for wolves, but because of the abundance of beavers in Voyageurs during the ice-free seasons, they’re not far behind deer on the menu.

Minnesota’s wolf population is estimated to be 2,700 animals, which is still small enough to be listed as a threatened species and protected from hunting.

RELATED – Watch: Grizzly Bear Versus Wolves

Research done by a team at Voyageurs Wolf Project (VWP) in the national park itself shows predators can transform ecosystems through what are called “trophic cascades.”

The positive effect of wolves on the moose population would be one example, along with the booming health of beavers in Yellowstone National Park since the reintroduction of wolves to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

In this study, researchers looked at the prevalence and effect of wolves killing a disbursing beaver: a beaver that is leaving an established colony to start a new colony of its own. That’s how beaver populations expand.

“In 2015, we documented a wolf killing a dispersing beaver in a newly created pond,” Austin Homkes, study co-author and field biologist with VWP, said in an interview. “Within days of the wolf killing the beaver, the dam failed because there was no beaver left to maintain it. The wolf appeared to have prevented the beaver from turning this forested area into a pond.”

Five years after the beaver killing that started the research project, the pond had yet to be colonized by another beaver.

RELATED – Wild Hunting Tactics: How 7 Apex Predators Do What They Do Best

Of the 42 ponds they monitored, 11 had beaver killed on them. Across the 11 wolf-altered ponds, data showed that the pond remained inactive for more than one year 100% of the time.

During the five-year study, wolf kills disrupted 88 beaver ponds. Those ponds would have held an estimated 51 million gallons of water across the 700-square-mile Greater Voyageurs Ecosystem.

Are Wolves Tipping the Scales?

Aside from whitetails, we know that wolves also eat moose. Obviously, they exist in close proximity at various times of the year. The jury is still out, though, on just how much of an impact their predation has on moose numbers.

As the population of wolves in Minnesota grows, it’s also easy to see how their effect on the region’s ecological succession, or change from forest to wetland to a riparian ecosystem, will also grow — which risks disrupting a far wider wildlife/habitat balance.

A perfect example: during the course of their normal day-to-day, beavers create moose browse by clearing out larger aspens and deciduous trees which allow smaller plants and shoots to grow. As wolves interrupt the beavers’ normal dam-building process, moose habitat is also disrupted.

As the wolf population grows to “recovered” numbers and they are eventually delisted in Minnesota as they have been in the West, there’s no question that there will be a need for practical, science-based management. The preservation of northern Minnesota’s rich and diverse ecosystems will depend on it.

READ NEXT – Will New Wolf Hunting Regs Kill Yellowstone-Area Tourism?

Comments