Since their reintroduction to Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho in 1995, gray wolves have been a blessing and a curse, depending on who you ask. The population’s strong recovery and subsequent removal from the endangered species list in Montana and Idaho 16 years later have now put the wolf-hunting and wolf-watching camps at odds with each other.

Wildlife managers need to control abundant wolf populations with harvest management (AKA hunting and trapping). At the same time, business owners in the Yellowstone Gateway area, who have come to rely on the wild, furry celebrities to bring in revenue via tourists who show up to get a look at them, understandably don’t want the animals to be killed.

“We are not anti-hunting. We support equitable fair chase and subsistence hunting. Both types of recreational tourism businesses deserve policy recognition in the context of wolves.”

—Wild Livelihoods Business Coalition

Bouncing back from almost complete eradication, wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountains have met and exceeded the US Fish and Wildlife Service criteria for a recovered population since 2002.

In Idaho and Montana, the gray wolf was removed from protection under the Endangered Species Act in 2011. They were delisted in Wyoming in 2016. Currently, wolves are hunted in Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana under state-controlled hunting regulations.

In December 2015, the agency estimated there were about 1,704 wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountain Distinct Population Segment, with an estimated 528 wolves calling the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem home.

Wolf packs are known to cover a territory of up to 1,000 miles depending on the abundance of prey and seasonal movement, so the lower number of wolves in the park is not surprising.

Ever since Jan. 12, 1995, when the first eight wolves arrived in Yellowstone from Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada, the public has been transfixed by the resurgence of the apex predators. In a part of the country that relies heavily on tourism for the lion’s share of its economy, the wolves, quite simply, became good business.

According to Wild Livelihoods Business Coalition, a group of local businesses and individuals in the Yellowstone Gateway area in southwest Montana, the top-ranked reason visitors come to Yellowstone is to see wildlife in the Northern Range; wolves are second only to grizzlies as the most sought-after animal to watch.

For 17 years, the wolves remained protected and garnered an unprecedented level of celebrity for a wild animal, and local businesses capitalized on the notoriety — of course, they still do today.

Last year, between January and October, 1,251,912 visitors flowed through the northern entrances of the park, and they spent approximately $80 million in the area while doing so.

RELATED – Watch: Grizzly Bear Versus Wolves

When the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks increased wolf hunting and trapping quotas this year, the animals’ celebrity status and associated tourist revenue ran up against the necessity for science-based wildlife management practices.

Quotas take into account population density and the carrying capacity of the area to mitigate disease risk and unwanted interaction with humans, livestock, and other wild animals. Something that the business coalition understands.

“Our business coalition contains members from the hunting and fishing industry, not to mention many members who hunt for subsistence,” the Wild Livelihoods website says. “We are not anti-hunting. We support equitable fair chase and subsistence hunting. Both types of recreational tourism businesses deserve policy recognition in the context of wolves.”

The department increased the state-wide wolf quota to 450 animals for the 2021–2022 season, which would account for roughly 40% of the total population in the state. Hunters and trappers are allowed a limit of 20 per season.

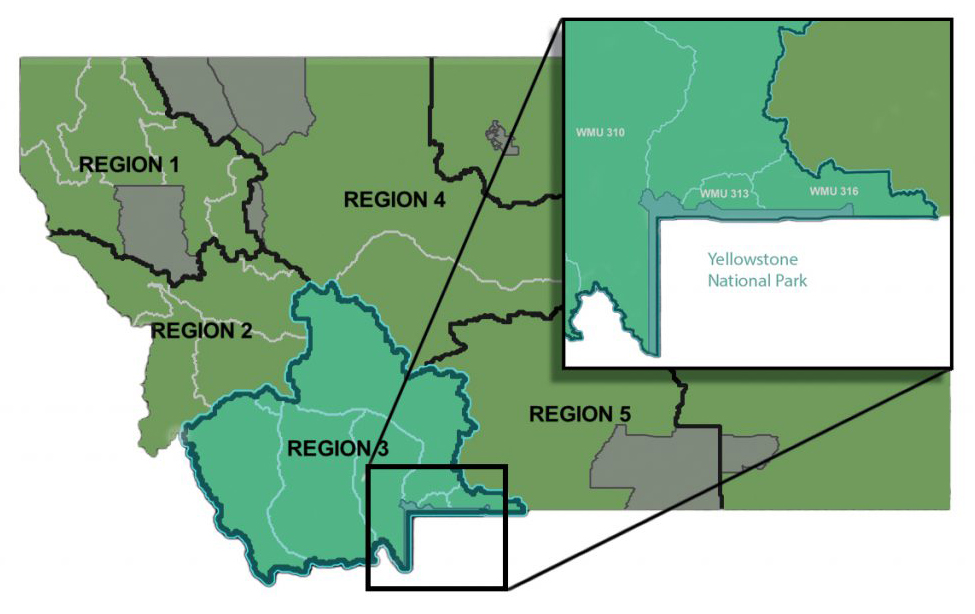

Individual regions have their own limits, though, so that wildlife officials can close seasons in specific areas when quotas are met, rather than allowing one region to simply continue stacking up animals.

“I know we’ve had many people watching Montana’s wolf hunting and trapping season this year,” said Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks Director Hank Worsech in a Jan. 20 press release. “However, harvest numbers in the state are very similar to years past. We’ll continue to monitor these numbers closely as the hunting and trapping season continues.”

But business owners in the area, who make big bucks off tourists who come to watch and not hunt or trap, say fewer wolves mean less money for them and their families.

RELATED – ‘Alarming’ Wolf Hunting Tallies Near Yellowstone Not Alarming at All

In an effort to protect their livelihoods, the business coalition is calling for a very specific change in quotas in Region 3 Wolf Management Units (WMUs) 313 and 316.

Region 3 is the collection of WMUs located in the southwest portion of the state, including units 313 and 316, which border the northern boundary of Yellowstone. Until this year, only one wolf was allowed to be killed in each of those WMUs.

This year, the individual quotas for 313 and 316 were removed.

Of the 181 wolves killed state-wide so far this season, 20 have been tagged in WMUs 313 (17) and 316 (3). Region 3 has reported 75 wolves harvested. The region’s quota is 82.

With the increased quota in Region 3 and the removal of quotas in WMUs 313 and 316, the business coalition rang the alarm.

As stated on the coalition’s website, “Now, theoretically, 82 wolves can be taken from those two units. They increased it 40-fold. What are the implications? Yellowstone Park has been averaging about 100 wolves park-wide; conservatively, 50% of the population might be expected to move in and out of WMUs 313 and 316.”

While the business coalition has an understandable bias toward protecting the extra-large canids, the chance of 82 wolves being killed in Region 3’s two smallest WMUs is slim to none.

Since 2009, wolf populations in the park have remained steady between 83 and 108, even with their delisting in 2011. As of January 2021, there were at least 123 wolves in the park, so the range remains consistent even with the current harvest numbers.

It also mirrors research presented in December 2020 by the FWP and Montana Cooperative Research Unit. The report states that from 2016 to 2019, the state-wide wolf population stabilized at an average of 190 packs and 1,136 wolves per year, even with hunting and trapping claiming less than 20%.

In other words, gray wolf populations in Yellowstone and the Northern Rockies are healthy and being managed so they may roam their home turf for generations to come.

RELATED – Grizzly Steals Kill From Yellowstone Wolf Pack – Again

Wolf Hunting in Other States

Wolf hunting is legal in a total of four states: Alaska, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Idaho, the other recipient of wolf reintroduction efforts in 1995, removed hunters’ daily and season limits for wolves in 2021. Hunters are only required to possess a legal tag for each wolf killed. The state estimates its wolf population to be roughly 1,500 animals.

It was also recently announced that Idaho’s Wolf Depredation Control Board will receive $1 million in 2023 for the continued support of wolf management efforts directed by the state fish and game department.

Wyoming has a 47-wolf limit in their Trophy Game Management Area, which borders Yellowstone. To date, only 29 wolves have been killed in the 2021–2022 season. Outside of the Trophy Game area, Wyoming Game and Fish doesn’t manage the predator, so there is no limit on the number of wolves that can be killed in a year.

Alaska is the only other state that allows wolf hunting in the US. Daily and season limits vary by Region and Game Management Unit. Wolves have never been endangered in Alaska, so hunting regulations are liberal.

Until this year, Wisconsin had been on the wolf hunting list, but greedy hunters screwed the pooch, so to speak. Wolf hunting was allowed in the state from 2012 until 2014, the year they were relisted as endangered. The season reopened in January 2021 but was closed after only four days because hunters killed 218 wolves, blowing past the 119-wolf limit that also included the tribal allocation for the Chippewas.

READ NEXT – The Current Status of Gray Wolves and Hunting in the US

Comments