There’s never been a good movie made about frontier legend Daniel Boone. It’s true. There were at least five announcements about remakes of movies from the 1980s and 1990s last month, but a guy who led one of the wildest frontier lives of all time hasn’t even gotten a low-budget biopic since the turn of the century, plus a few decades. There were two forgotten films made about Boone: one came out in 1956 and the other in 1936, and that’s it. What gives?

Technically, you can kinda sorta count Last of the Mohicans (1992) since Boone is widely thought to be James Fenimore Cooper’s inspiration for Nathaniel Bumppo, the protagonist of his classic Leatherstocking Tales novels, but that’s a stretch. (Mohicans is a version of the real-life story about Boone rescuing his daughter after she was kidnapped.)

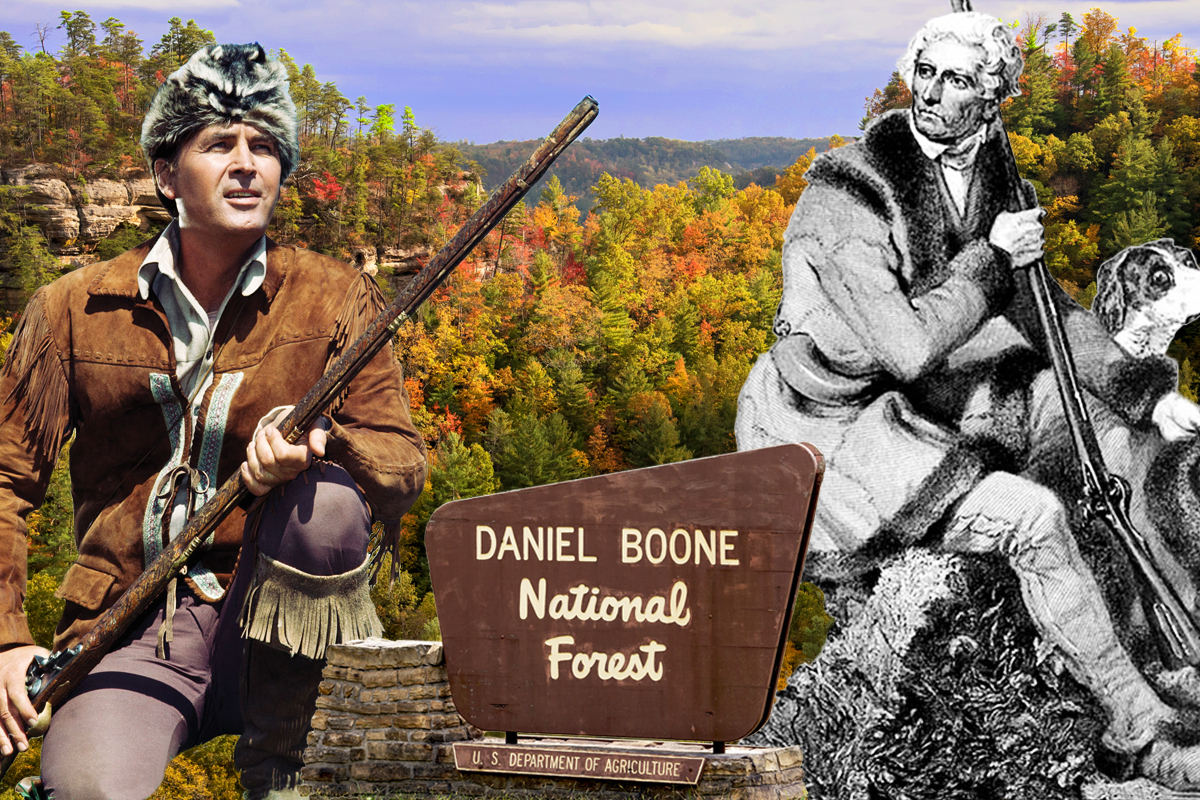

But in the past 65 years, there has not been a single film about the life of Daniel Boone, in part or full. Some of the tallest tales about this legendary hunter and frontiersman were retold in the 1960s on the small screen, keeping his legend alive, but that’s about it.

In December 1960 and in March 1961 the forgettable Daniel Boone mini-series was broadcast on Walt Disney Presents on ABC. It was loosely based on Boone’s real-life story, and he was played by a guy named Dewey Martin. I never heard of him either.

A couple of years later, producers at NBC and 20th Century Fox wanted to make an action-adventure series out of Disney’s hugely successful Davy Crockett short films starring Fess Parker from the 1950s, but Disney wouldn’t sell the rights. Apparently, acquiring the rights to Daniel Boone’s story wasn’t a problem.

NBC hired Parker, plopped a cookskin hat on him, and he played Davy Crockett once again, just reskinned as Daniel Boone for six whole seasons that were shot entirely in California and Kanab, Utah. The Daniel Boone show ran from 1964 to 1970 on NBC for 165 episodes and was quite popular.

And since The Ballad of Davy Crockett was such a hit, they slapped a similar theme song on it (above), but with way worse lyrics. Read those and realize that multiple people signed off on this shit and that fans listened to it at the top of every episode for six years — and they were okay with that. A guy named Ed Ames released the song as a single in 1966.

This show is probably the most prominently the frontiersman has ever been featured in an element of pop culture, and he’s a stand-in for somebody else.

While there are monuments, national parks, and even towns named after him all over the place, everyone knows if a historical figure isn’t immortalized in pop culture, they’re basically forgotten. (I kid, but not really.) Why does Boone deserve a movie, or at least a better on-screen representation than he’s had, other than the fact it hasn’t really been done before and audiences are desperate for something at least a little original?

Let’s do a run-down of all stuff in Boone’s life that would translate really well to the screen. There’s a lot.

Daniel Boone: The Famous Kentuckian From Pennsylvania

While Boone is synonymous with Kentucky, he was actually born in Pennsylvania on Oct. 22, 1734, to a Quaker family when Kentucky wasn’t really a thing yet. His father, Squire Boone, was a weaver and a blacksmith. In 1731, the Boones made their home near the place that would become Reading, and that’s where Daniel was born.

Pennsylvania was the American frontier at the time, and Boone interacted with and learned from Native Americans and rough-living settlers his whole young life. Most importantly, they taught him how to hunt. By his teens, Boone was well-known in the region for his hunting prowess.

“No matter what was going on, every fall Boone would go on long hunting expeditions into the deep wilderness that lasted weeks or months, either solo or with a small group of hunters. “

An often-told story about young Boone recounts the time he and some friends were set upon by a mountain lion in the woods one day. When the cat charged, his friends scattered, but Boone stood his ground, calmly cocked and aimed his rifle, and shot the animal through the heart as leaped at his throat. Is it true? It’s so awesome, who cares.

Some static with the local Quaker community got Squire Boone kicked out of the church and the family relocated to Davie County, North Carolina where Daniel kept hunting and avoided formal education the best he could. Some said Boone was semi-literate, but he was actually tutored by family and likely wasn’t any more illiterate than most men of the time who made a living with a gun in the woods. Others said he was actually a big reader and would often read aloud by the fire in hunting camp; he was partial to Gulliver’s Travels.

Going to War, The First of Many

Daniel Boone was no stranger to combat throughout his life. When the French and Indian War broke out in 1754, he and his cousin, Daniel Morgan, joined a militia company in North Carolina fighting under Capt. Hugh Waddell for the British against the French and their Native American allies. Boone worked as a teamster and blacksmith.

Waddell’s company was part of Gen. Edward Braddock’s forces when they tried to drive the French out of Ohio Country. It didn’t go so well, and ended with the bloody Battle of the Monongahela. Though Boone mostly remained at the rear during the battle, he was nearly killed when enemy forces attacked the baggage wagons. Boone escaped, as did Morgan, who went on to become a key general in the American Revolution.

During this time, Boone met John Finley, a packer who had worked for George Croghan in the trans-Appalachian fur trade. Finley talked up the abundance of game in the Ohio Valley, and Boone never forgot about it. That would make for a cool first act — just saying.

Fighting, Hunting, and a Love Triangle?

It took about 12 years for Boone to actually make it to Kentucky. First, he returned home and married his neighbor, Rebecca Bryan. The couple eventually had a brood of 10 children and raised another eight children of deceased relatives.

Things heated up between British colonists and the Cherokee in 1758. Boone’s family fled to Culpeper County, Virginia as he again took up arms under Capt. Waddell in what became known as the Cherokee Uprising or the Anglo-Cherokee War.

When he wasn’t fighting, Boone made a living as a market hunter and trapper. No matter what was going on, every fall he would go on long hunting expeditions that lasted weeks or months, either solo or with a small group of hunters. In the fall he hunted deer, and he trapped beaver through the winter. In the spring, the deer skins and beaver pelts were sold to commercial fur traders. Sounds like a pretty sweet life.

A movie about Boone wouldn’t be all about hunting and battles; it could even have some love-triangle-type intrigue. As one story goes: Boone returned home from a long absence — longer than nine months, at least — to find Rebecca had given birth to a baby girl. She said he’d been gone so long that she thought he’d died in the wilderness, and that the baby was fathered by Boone’s brother.

Apparently, Boone was super cool about this, didn’t begrudge Rebecca, and raised the girl as his own. No word on how he felt toward his brother after that. Like many wild stories about Boone and other frontiersmen of the era, this may be campfire bullshit, or not, but the identity of the daughter and brother have a way of changing in different tellings, which isn’t a good sign — but embellishment is Hollywood’s bread and butter!

Boone Goes to Kentucky

Craving a new location with fewer people and better hunting, Boone remembered what Finley told him about Kentucky’s abundant game years earlier. In May 1769 Boone set out with a party of five men for a two-year expedition to thoroughly explore Kentucky. This part could be a movie on it’s own, by the way.

The only problem was, the Shawnee and other Native tribes considered Kentucky their hunting grounds. Boone and one of the men in his party were captured by the Shawnee, who took their furs and skins but set them free.

Boone gave no shits and continued with his hunting and exploring of Kentucky, not returning to North Carolina until 1771. He came back to Kentucky in the fall of 1772, and the following year his extended family and about 50 others became the first to attempt a British settlement there.

The Death of Boone’s Son and Dunmore’s War

As you may have guessed, there were already plenty of people living in this “new” country and they were getting increasingly concerned about the influx of white settlers.

A group of Delaware, Shawnee, and Cherokee warriors set upon a few of Boone’s party as they were traveling to another location. The group included Boone’s oldest son, James, William Russell’s son, Henry, and an enslaved person, Charles, who were all taken captive. The warriors decided to make an example of them. Another enslaved person, Adam, avoided capture and watched from a hiding spot on a riverbank as James and Henry were stabbed and hacked to death.

Adam fled and was lost in the woods for 11 days before finally finding Boone’s group and telling them what happened. They later discovered Charles had also been killed. His body was found 40 miles from where he and the others were taken captive.

The news spread throughout the frontier, and Boone’s party abandoned the expedition. The murders helped stoke a conflict known as Dunmore’s War, which saw fighting between the Virginia Colony and Native Americans for control of what is present-day West Virginia and Kentucky. Boone again took up arms and was promoted to captain in the militia. The war ended after the Battle of Point Pleasant in October 1774, a Virginia victory that forced the Shawnee to relinquish Kentucky.

Transylvania, USA and Boone’s Trace

After the short war, Boone was hired to establish the new colony of Transylvania. Yep, that’s right. At least part of what is now Kentucky was almost called Transylvania. The British just loved naming shit after other older shit.

He traveled to several Cherokee towns to invite them to a big meeting at Sycamore Shoals in March 1775 where prominent judge Richard Henderson bought the Cherokee claim to Kentucky.

Boone then made his famous journey through the Cumberland Gap into central Kentucky, blazing what was then called Boone’s Trace. A trace is a torn-up swath left in the wake of a large herd of animals, like buffalo, as they pass through an area. This later became known as the Wilderness Road.

He founded the inventively named Boonesborough, aka Fort Boonesborough, on the Kentucky River and a few other settlements. Boone sent for his family and more settlers in September 1775, despite occasional attacks by Native war parties on the young settlements.

Daniel Boone and the American Revolution

Yeah, there’s a lot more to ol’ Danny-boy’s story. Each of these chapters could make for a solid movie script of their own.

When the American Revolution began in 1775, things got hot in Kentucky. Native tribes saw the colonies’ focus on the war as an opportunity to drive out the unwanted settlers, and later, their efforts were aided by the British. Frequent attacks were launched as part of a guerrilla campaign to convince settlers to flee, and some did. By the spring of 1776, the only people left in the fortified towns of Boonesborough, Harrodsburg, and Logan’s Station were the Boone family and about 200 colonists.

Boone Rescues his Daughter

Boone’s daughter, Jemima, was captured by a Native war party on July 14, 1776, along with two other girls and taken north. Immediately, Boone and a posse of men from Boonesborough set out to track them down. It took two days for the posse to catch up to them and successfully ambush the war party. All three women were rescued, safe and sound. This is the famous Boone story that Cooper immortalized with his fictionalized version in The Last of the Mohicans.

During the rest of the revolution, Boone fought lesser-known battles in Kentucky. In 1777, the British began recruiting Native Americans to attack settlements in the area, and the militia of Kentucky County, Virginia was formed in Boonesborough. The fort town was soon sieged by British-allied Shawnee. Boone was shot in the ankle while fighting outside the fort, but was dragged inside and recovered. The attacks continued and Boonesborough’s crops and livestock were destroyed.

Captured, Adopted by the Shawnee, and Court Martialed

To preserve the meat they had left through winter, they needed salt. Boone led 30 men to nearby salt springs and was captured while hunting alone by Shawnee warriors on Feb. 7, 1778.

Realizing his group was heavily outnumbered, Boone led the Shawnee and Chief Blackfish back to his camp and surrendered. Boone negotiated with Blackfish and persuaded him to allow the residents of Boonesborough to remain until spring when they would all surrender without a struggle. Blackfish bought Boone’s bluff, and so did some of Boone’s own men.

Boone’s silver tongue got his men out of hot water, but he didn’t get to go home. The Shawnee custom was to adopt some prisoners to replace dead warriors, and Boone was adopted into a Shawnee family at Chillicothe and given the name Sheltowee (Big Turtle).

So check this out; this is some action-hero shit right here: Blackfish brought Boone with him to meet with Lt. Gov. Henry Hamilton, the commander of the British Fort Detroit during the war. Boone refused Hamilton’s request for him to be turned over to the British and continued the deception that his town would surrender in the spring while electing to stay with the Shawnee.

In June, Boone learned that Blackfish was preparing to attack Boonesborough with a large force, despite their fake agreement. Staying with the Native Americans so he could keep a close eye on them had paid off. Boone escaped on horseback, which he could have apparently done at most any time, and proceeded to travel 160 miles to Boonesborough in five days; he rode his horse to death, and continuing on foot.

When he arrived home to warn of the attack, some people didn’t trust him because of his bullshit promise to Blackfish and because he’d lived with the Shawnee for so long. To convince them, Boone led a raid against the Shawnee and then successfully defended the town against a 10-day siege led by Blackfish in September.

After all that, charges were brought against Boone and he was court-martialed! He was found not guilty and even got a bump in rank afterward, but Boone took the court martial personally and reportedly rarely ever spoke of it.

Boom, that’s a whole movie right there.

A New Town for Daniel Boone and the Revolution Continues

After a brief time in North Carolina, Boone brought his family back to Kentucky in late 1779 along with a large party of emigrants. Cool fact: that group included Capt. Abraham Lincoln and his family, the grandfather of President Lincoln.

Boone decided he was done with Fort Boonesborough, but still wanted to live in a place with his name on it, so he founded Boone’s Station and made a business of locating land for settlers in the area, an in-demand service at the time. The would-be colony of Transylvania went bye-bye when Virginia created Kentucky County, so all new land claims had to be filed with Virginia. Boone had become a leading citizen of Kentucky.

Kentucky was divided into three Virginia counties in 1780 and Boone was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the Fayette County militia. The following year he was elected as a representative to the Virginia General Assembly in Richmond, and the year after that he was elected sheriff of Fayette County. All the while, the revolution raged on, and Boone wasn’t out of the fight.

He and his brother Ned were part of the invasion of Ohio Country in 1780 and fought in the Battle of Piqua against the Shawnee in August. On the return trip, while the Boone brothers were hunting, Shawnee warriors ambushed them and killed Ned.

Ned greatly resembled Daniel, so much so that the Shawnee decapitated him and took Ned’s head as evidence that Daniel Boone had been killed.

In Jail While Yorktown Falls

Just before the revolution began to wind down, Boone attempted to go to Richmond to take his seat in the legislature in October 1781 and was captured by the British near Charlottesville. He was only imprisoned for seven days, but during that time, Gen. Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, marking the beginning of the end of the American Revolution.

But the war wasn’t quite over for Boone in Kentucky. In August 1782 he fought in the Battle of Blue Licks between Boone’s Kentucky militiamen and a group of 50 Loyalists and 300 Native Americans. It was one of the last battles of the war and a terrible defeat for the Kentuckians, during which Boone’s son, Israel, was killed.

The Final Chapter of Daniel Boone

That’s just all the action-movie stuff. If some filmmaker wanted to do a period drama with all that cool stuff as a backdrop, there’s plenty more story in Missouri.

After the war, Boone settled into life as a politician and businessman until 1799 when he moved to what is now St. Charles County, Missouri. At the time, this was outside US borders and part of Spanish Louisiana.

The Spanish governor appointed Boone as syndic, which was a judge and jury combined, and as a commandant of the Femme Osage district. He served until 1804 when Missouri became part of the US in the Louisiana Purchase. He was then appointed captain of the local militia.

He spent his last years in Missouri hunting and trapping as much as he could. For good measure, he was captured one more time by Native Americans; this time it was an Osage tribe, and they took his pelts for hunting on their land.

At the ripe old age of 76, Boone went on a six-month group hunt in 1810 up the Missouri River. Some say the hunters went as far as the Yellowstone River, which would have been a round trip of 2,000 miles or more. Make that movie and get Gene Hackman out of retirement to play Boone. It could work.

By the time the War of 1812 rolled around, his sons Daniel Morgan and Nathan went to fight, but Boone was finally too old to charge off into battle again.

One Last Tall Tale

Boone died on Sept. 26, 1820, at Nathan Boone’s home in Missouri and was buried next to Rebecca, who had died in 1813, but even his death has a bit of adventure and some mystery to it.

The graves remained unmarked until the mid-1830s. The Boones were reinterred in Frankfort, Kentucky in 1845, but some in Missouri say his body never left the state and remained in a different grave.

Today, both the Frankfort Cemetery in Kentucky and the Old Bryan Farm graveyard in Missouri claim to be Boone’s final resting place. There’s a whole book on it. There you go, that’s another movie. Or episode. Or limited-series chapter. Whatever.

There is so much great material here that somebody has to make a film, or a trilogy, or a really good series that tells the life story of this amazing American who lived during one of the most interesting times in our country’s history and was knee-deep in all of it for decades.

Read Next: More stories from FRA Managing Editor David Maccar.

Hunter says

There is a very nice book written by Matthew Pearl named “The Taking Jemima Boone” although it’s in three parts but a fourth chapter could easily have been added as you mention above after the killing of his brother Ned.