Election years throughout the more than 200-year history of the United States are often rife with contention, political upheaval, social unrest, and surprise. On Jan. 7, 1789, Congress required state electors for the nation’s first presidential election; George Washington took the oath of office a month later. The Electoral College system was present from the beginning, as the Constitution enabled the positions of president and vice president to be chosen by these state electors, as opposed to the popular vote of the people.

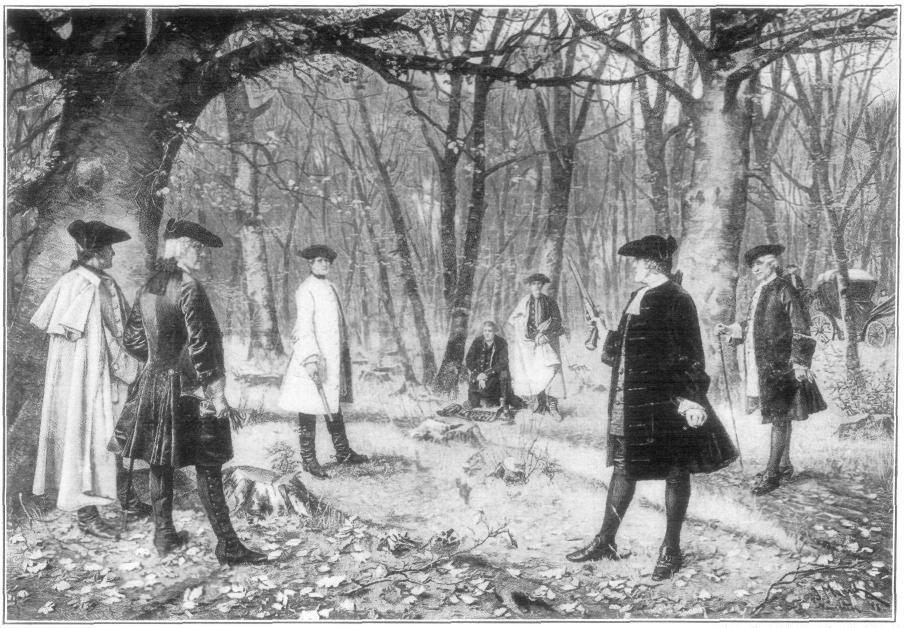

It didn’t take long for controversy to erupt in the political arena. The fourth presidential election in 1800, during which Thomas Jefferson and John Adams faced off, ultimately led to sitting Vice President Aaron Burr killing Alexander Hamilton four years later in a duel.

Members of the Electoral College had two presidential votes. At the time, the candidate with the highest number of votes would become president, and the second-place vote-getter would become vice president. Jefferson and Burr prevailed over the ticket of Adams and Charles Pinckney, but they tied each other with 73 votes apiece. The tiebreaker went to the House of Representatives.

The tie emboldened Hamilton to campaign against Burr in support of Jefferson, even declaring, “Mr. Burr loves nothing but himself — thinks of nothing but his own aggrandizement.”

These were far from the worst accusations thrown about during the campaign, mirroring the hostilities of 21st-century politics. John Adams was accused of having a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman,” by Republican newspaper editor James Callender. The president of Yale University, minister Timothy Dwight, insinuated in a widely reprinted sermon that if Jefferson were to win the election, “murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest will be openly taught and practiced.”

The political turmoil between rivals, both of whom the general public viewed as Revolutionary War heroes, resulted in the outrageous outcome of the fatal duel, and indirectly to the amendment of the Constitution. Prior to the 1804 election, the 12th Amendment passed to ensure separate ballots for president and vice president.

Although we seem to have left duels between political figures behind in the 19th century, many bizarre, obscure, and wacky things have happened in the proceeding years, some of which are reflected today as we approach another US election in 2020.

America’s First Female President?

There has never been a female president of the United States, but that doesn’t mean influential women haven’t tried over the years. Victoria Woodhull was the first woman to throw her hat into the presidential race in 1872, and she had quite the resume. Her father had enlisted her to use her “abilities” as a traveling fortuneteller during the American Civil War. Alongside her sister, Tennessee, she contacted spirits, gave massages, sold healing elixirs, and formed other money-making schemes to take advantage of people.

As a seasoned con artist, she knew how to think on her feet. The Woodhull sisters were hired by railroad mogul Cornelius Vanderbilt and later became the first female stockbrokers on Wall Street. The pioneering women were advocates for the women’s suffrage movement, but despite all of their successes, Victoria’s shady past was later exposed during her presidential campaign. Seeing value in female voices, Victoria was known as the first woman to publish a weekly newspaper. One of her articles was a defamatory piece exposing the double life of preacher Henry Ward Beecher. The backlash caused her to spend Election Day in jail on the charges of sending obscene material through the mail.

Presidential Campaign from a Jail Cell

Eugene Debs was a notorious proponent for free expression, and he unsuccessfully ran for president on the Socialist Party ticket during the 1900, 1904, 1908, and 1912 elections. On June 16, 1918, during the height of the United States’ involvement in World War I, he gave a scandalous speech from a park in Canton, Ohio.

“The working class have never yet had a voice in declaring war,” Debs said. “If war is right, let it be declared by the people — you, who have your lives to lose.”

His speech was not well received. The Chicago Tribune ran a story with the headline: “Debs Wakes Up Howling At War; U.S. May Get Him.” As election night for the 1920 presidential race approached, Debs was not present. While other candidates were neatly dressed in suits and fancy hats, Debs was wearing denim, known only as Prisoner 9653. Debs issued a handwritten statement from his jail cell in Atlanta Federal Penitentiary: “I thank the capitalist masters for putting me here. They know where I belong under their criminal and corrupting system. It is the only compliment they could pay me.”

The Sedition Act of 1918 considered the expression of antiwar views as an act of treason. Debs was found guilty and convicted to serve a 10-year prison sentence; however, in 1926, he died from a heart condition.

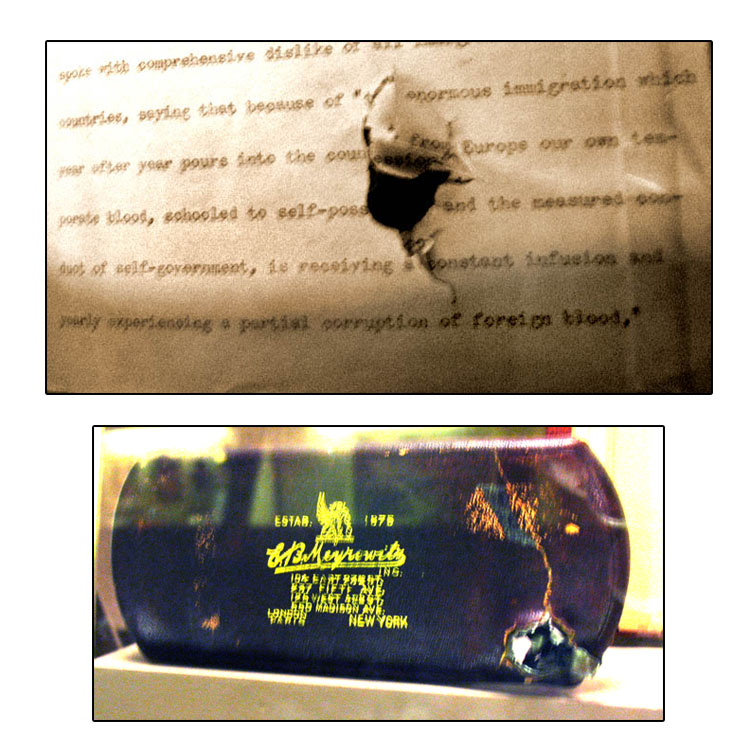

The Speech that Saved Teddy Roosevelt’s Life

Scheduled to deliver a speech to a packed auditorium in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, presidential candidate Teddy Roosevelt left the Gilpatrick Hotel to enter a waiting car. At around 8 p.m. on Oct. 14, 1912, a large crowd greeted Roosevelt as he stepped out of the car onto the floorboard to wave to his supporters. From out of the crowd, John Schrank pulled a .38-caliber pistol and fired at close range, hitting Roosevelt in the chest. The bullet entered his eyeglasses case and pierced through his 50-page manuscript — objects he had nestled in his coat pocket. When he opened his vest, his shirt revealed a blood-soaked wound.

“It takes more than that to kill a bull moose,” Roosevelt quipped. “Fortunately I had my manuscript, so you see I was going to make a long speech, and there is a bullet — there is where the bullet went through — and it probably saved me from it going into my heart. The bullet is in me now, so that I cannot make a very long speech, but I will try my best.”

Roosevelt spoke for the next 84 minutes before going to the hospital to receive treatment for his gunshot wound.

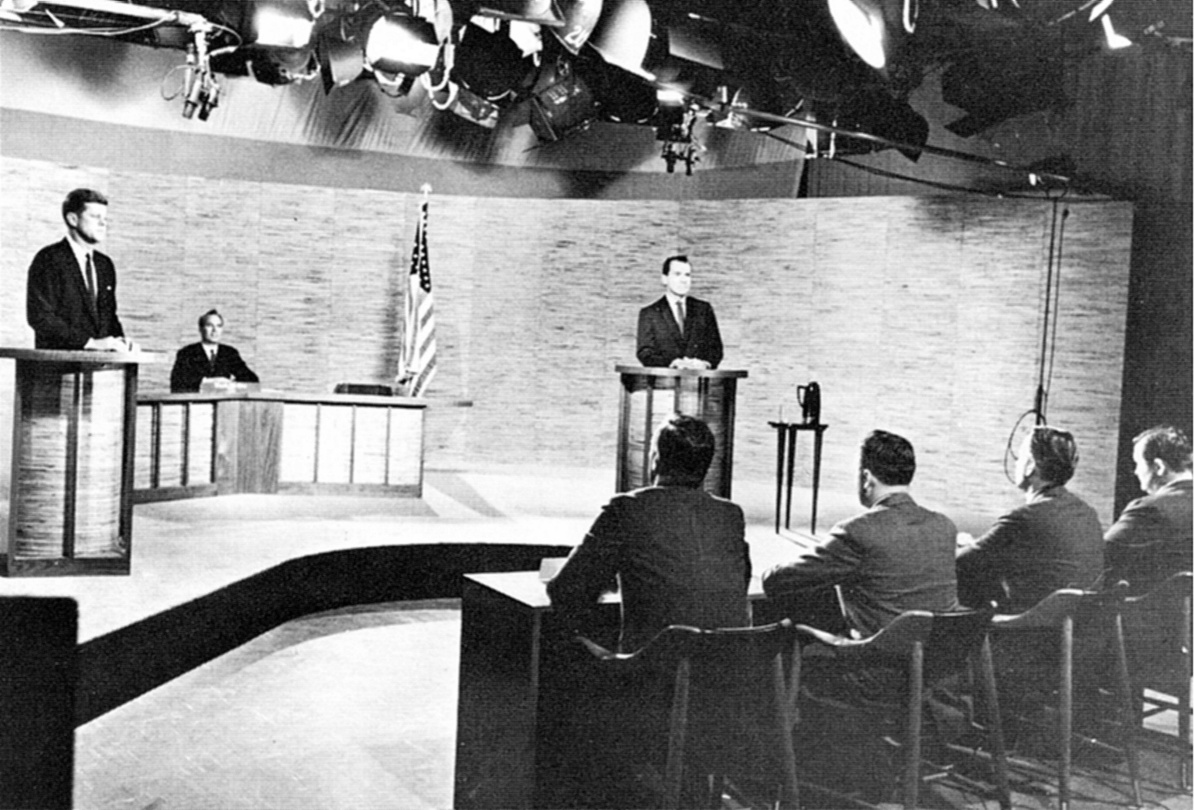

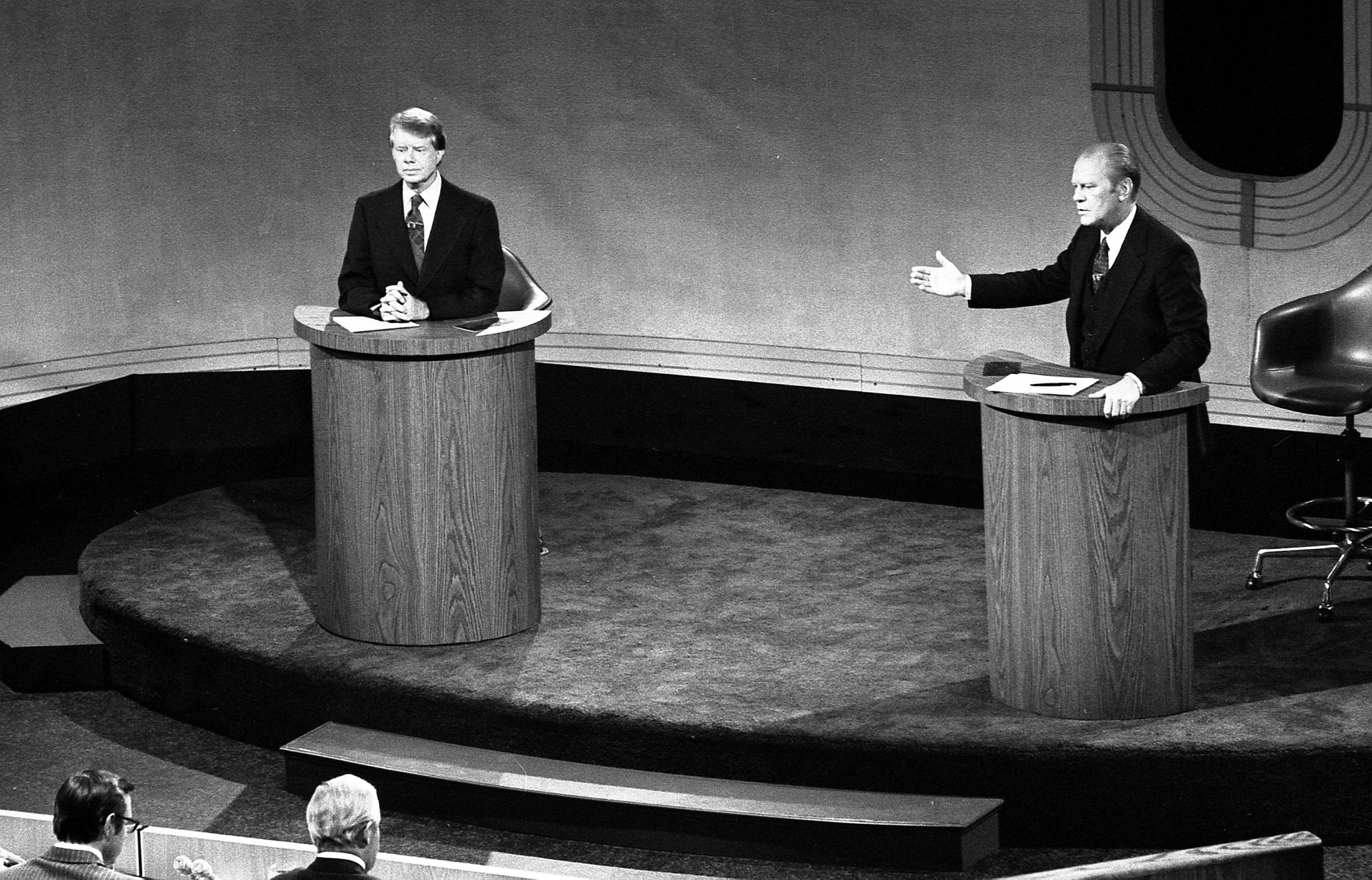

Televised Debates & Political Advertising

The first official televised presidential debate was between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960. However, this deserves an asterisk because four years earlier, two surrogates for Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson and Republican president Dwight Eisenhower took to the stage. On Nov. 4, 1956, the two surrogates, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt for the Democrats and Maine Sen. Margaret Chase Smith, debated issues on network television.

Political debates on TV surged through the 1960s, as did political advertisements. On Sept. 7, 1964, a 60-second advertisement from Lyndon Johnson’s campaign shocked the nation by insinuating that presidential candidate Barry Goldwater was a loose cannon with his finger on the trigger of nuclear war.

In the opening of the TV ad, a freckle-faced 3-year-old girl is seen picking daisies and counting from one to 10. As she reaches the number nine, a man’s voice interrupts her from a loudspeaker, beginning a countdown. As the camera zooms through the eyes of the child, a mushroom cloud appears in the wake of a nuclear explosion.

“These are the stakes, to make a world in which all of God’s children can live, or to go into the dark,” comes a voice-over of Johnson amid the destruction. “We must either love each other, or we must die.”

A narrator finalizes the message with “The stakes are too high for you to stay home.” Well known today as “The Daisy Bomb Ad,” it is considered one of the most successful political attack ads in US history because it preyed on the emotions of its viewers.

Comments