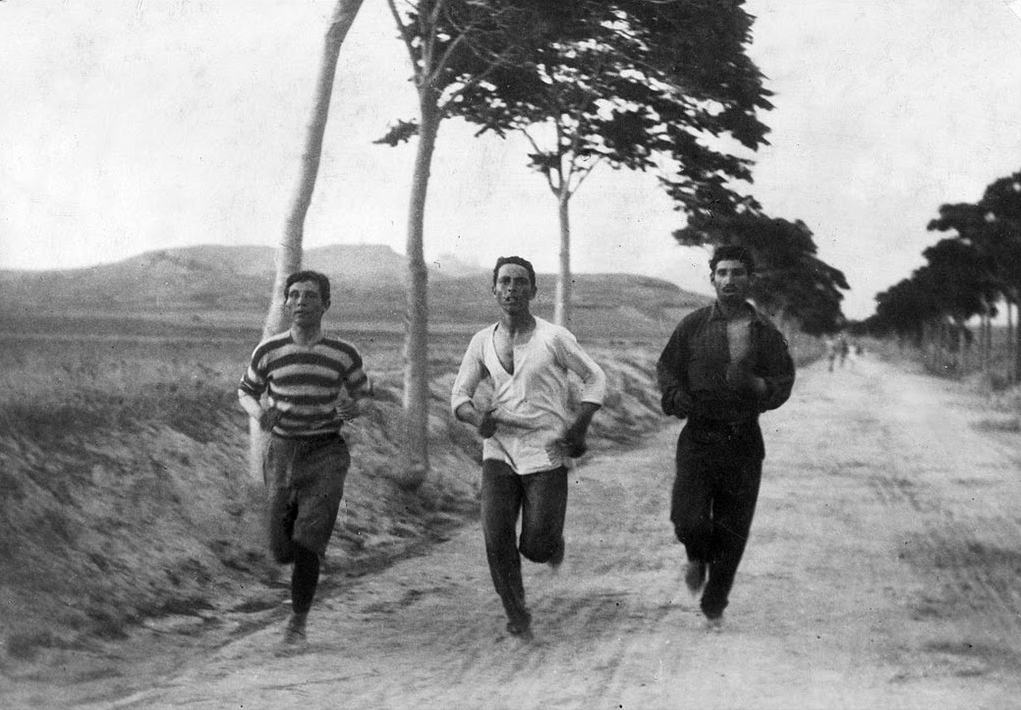

6 a.m. — At the trailhead of the Illinois and Michigan Canal State Trail, three runners silently step up to the starting line through the morning fog. There are six spectators on hand. The trio of runners have their arms folded against the early morning chill. They run in place to keep warm. Then, the starter gives the signal, and the runners unceremoniously shuffle off into the mist. They have 123 miles to go.

Tony Cesario shows up on the Chicago lakefront at 5 p.m. for his second 10-mile training run of the day. He does a few halfhearted stretches and munches on an energy bar as groups of runners whiz by. Many are wearing spandex running tights with futuristic designs. Some have on bright neon Nike tank tops made of a special moisture-wicking material that’s a spinoff from the space shuttle program. Almost all have headphones in their ears.

Cesario’s running shorts are old, with a brand label that long ago rubbed off in the wash. The 57-year-old bank vice president wears a wrinkled cotton Chicago Cubs T-shirt with cutoff sleeves. He takes off his wedding ring and weaves it through a crucifix necklace. “Sometimes my fingers swell if I’m dehydrated,” he offers, tucking the necklace back under his shirt. Cesario’s shoes are from the bargain rack at Payless and he doesn’t listen to music when he runs.

Unimpressed by the 26.2-mile challenge of the marathon, the father of two is part of a tribe of athletes who routinely complete races of 50, 100, even 200 miles. They’re called ultrarunners, and they have redefined the limits of what the human body can endure.

In this extreme sport whose champions receive scant fortune and fame, the obvious question that comes to mind is: Why? Perhaps, more accurately: Why the hell?

The answer is hard to understand.

The prize, you see, is to suffer.

11 a.m. — After running 26 miles, the length of the marathon, Tony Cesario gets his first blister. He’s just getting warmed up.

In 490 B.C. the Greek messenger Pheidippides ran 26 miles from a battlefield on the plains of Marathon to his hometown of Athens with news of the defeat of the Persian army. Legend says that Pheidippides burst through the gates of Athens, exclaimed, “Victory!” and then promptly died of exhaustion.

Pheidippides’ journey was transformed into an Olympic event in the 1896 Games in Athens and was called the “marathon.” Only 17 athletes competed in the inaugural event, and it wasn’t until the 1908 London Olympics that the official distance was set at 26.2 miles — the extra 0.2 was added to ensure the race finished directly in front of the royal box of King Edward VII.

Truth is, marathons used to be a big deal, but they’re hardly worth bragging about these days. The event swelled in popularity during the running boom of the 1970s, transforming what was once the domain of hardcore athletes into athletic mega-spectacles. In 2016, for example, more than 508,000 people completed marathons in the United States.

Big-city marathons now more closely resemble wildebeest migrations across the Serengeti than elite athletic events. The 2019 New York City Marathon counted 53,627 finishers, making it the world’s largest marathon in history. The field of runners in New York was so enormous, in fact, that it took more than an hour just to pass through the starting gate.

As the marathon evolved into a routine athletic affair, a select group of runners began to search for a new, more daunting test of grit.

“After a while, doing marathons in high school and in college, you’re like, well, what’s next?” Cesario says. “I had done that for a while and I wanted a bit more, so even after the 50-miler, all I could think about was doing the 100. After the 100, I was like, okay, I did that, can I do a little more? You know you’re always trying to push yourself, otherwise you’re like, I got there, now what?”

Officially, ultramarathon running started in 1921 with the 55-mile Comrades Marathon in South Africa. Subsequently, over the intervening decades, the appeal of even longer races has slowly but steadily increased. And ultrarunning, too, has become more mainstream. Yet, despite the exploding popularity of marathons, running ultras still remains somewhat of a fringe pastime. Admittedly, the distance has amassed a devoted following in recent years due to some popular books, such as Christopher McDougall’s runaway (excuse the pun) bestseller, Born to Run.

In any case, only 319 runners finished the 2019 Western States 100, the most popular ultramarathon in the United States. Held annually in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, the Western States 100 is the oldest 100-mile race in the world. Still, the modest size of its finishing field is a far cry from the tens of thousands who typically trudge across the finish lines of the world’s big-city marathons. And it’s not just the size of ultramarathon events that makes them so unique; their atmosphere, too, sets them apart.

One of the most popular standard-distance marathons in the US — the Rock ’n’ Roll Marathon Series — features racecourses with bands jamming every few miles as the runners plod past. Participants sometimes don costumes, including the inevitable guy dressed up as Elvis. The events have more in common with Lollapalooza than their ancient Greek roots.

In stark contrast, ultras are often run on deserted mountain trails or forgotten paths through forests. The fields of athletes are usually capped at a few dozen to abide by the regulations of the state and national parks through which they frequently pass. The few events on pavement, such as the Florida Keys 100-mile race, are open to traffic, forcing athletes to shuffle along the shoulders of busy highways. But that’s the way the runners want it. Simple. Pure. Uncommercial. The sport’s star athletes — more cult heroes than celebrities — often champion Spartan lifestyles, which allegedly awaken an instinctive appreciation of the world that’s been lost in the hyperconnected hubbub of modern life.

After all, as McDougall’s book title declares — our species was “born to run.”

“Perhaps the genius of ultrarunning is its supreme lack of utility,” writes David Blaikie, former president of the Association of Canadian Ultramarathoners.

“It makes no sense in a world of space ships and supercomputers to run vast distances on foot,” Blaikie continues. “There is no money in it and no fame, frequently not even the approval of peers. But as poets, apostles and philosophers have insisted from the dawn of time, there is more to life than logic and common sense. The ultra runners know this instinctively. And they know something else that is lost on the sedentary. They understand, perhaps better than anyone, that the doors to the spirit will swing open with physical effort. In running such long and taxing distances they answer a call from the deepest realms of their being — a call that asks who they are.”

For Cesario, the daily training alone offers a welcome release from the stress of modern life. “Believe it or not, with all of the miles you put in there’s a certain tranquility that comes with it that you aren’t gonna get anywhere else,” Cesario says. “To me, that’s the peace, you know? With all the chaos that goes on during the day, you know you can come out here and just put your miles in.”

7 p.m. — After running 60 miles, Cesario vomits for the first time. As he’s changing socks, four of his toenails fall off. His body is beginning to fail. He is halfway done.

One might assume that an athlete who routinely completes superhuman feats of endurance might have the physique of a Greek god. The truth is, Cesario looks, well — normal. The Chicago native stands 5 feet 8 inches tall. He has a thin, fit frame, with drawn cheeks that indicate a low body fat level, but otherwise his physical appearance is unremarkable. His muscles look toned, but not out of the ordinary. He has a friendly demeanor that exudes no bravado or hyperinflated ego. Basically, he looks and acts like your typical, if fit, middle-aged guy.

But there is something special about Cesario when he runs. Other runners pound by along the Chicago lakefront, pumping their arms forcefully, trying to muscle their bodies forward. When Cesario runs, the genius of his stride is hard to miss. He glides. The ground passing beneath his feet seems to flow like water. There isn’t an ounce of wasted movement or inefficiency. All of his momentum is directed forward; his head doesn’t bounce at all. In effect, his running looks effortless. One is fooled into thinking: If only I could run like that, maybe 100 miles would be possible …

But the fact is that running 100 miles sucks. “Your knees are going to hurt,” says Cesario. “I take ibuprofen pretty regularly, pretty much every two hours, and that keeps your feet and knees from hurting too bad. But by the end, you just want to get through it.”

While runners in regular marathons trot by aid stations every mile or so to grab a cup of Gatorade or a piece of banana, ultramarathon aid stations (sometimes separated by 10, 15, even 20 miles) seem to have more in common with a battlefield triage unit. Athletes stagger in one by one and are met by anxiously awaiting teams of family and friends. The athletes’ bodies are bloodied and broken. Some sport vomit stains on their shirts. Some have lost control of their bowels. Doctors circulate the area, applying IVs and dressing blisters that have rubbed through skin, exposing the flesh below.

“We have peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, we have Gatorade, we have Gatorade mix, we have Perpetuem, we have ginger tablets, we have salt tablets, we have anti-diarrhea tablets — so you’re almost like a walking medicine cabinet, making sure you have everything covered, just in case,” Cesario says. “And if all else fails, the aid station people usually have something for you. And Advil and ibuprofen is always in the mix.”

The surprising thing is that achy joints and lack of fitness are not the most common crushers of ultrarunning dreams. Rather, food is often the overriding obstacle to success.

Imagine the meat patty of a McDonald’s Quarter Pounder. Now imagine 136 of them in a pile, stacked one on top of the other more than 3 feet high. That is roughly the amount of biomass that your body has to cannibalize to run 150 miles — the distance of Cesario’s longest run to date.

“Ultramarathons are basically an eating and drinking contest, with a little exercise and scenery thrown in,” McDougall writes in Born to Run.

The energy expenditure of ultrarunning is incredible. Athletes burn roughly 200 calories for every mile of trail running. That equates to 10,000 calories for every 50 miles. By that measure, a 150-mile ultramarathon requires 30,000 calories. And the athletes deplete more than just their energy reserves. Prolonged exercise dehydrates the body and drains the blood of vital electrolytes, minerals, and vitamins.

“The low point is when your nutrition drops,” Cesario says. “All of the sudden your sugar is low, you’re hungry and you have no energy, and they call that the bonk. You’re gonna hit that a couple times in an ultramarathon. Knowing that you’re gonna hit it, you need to know that you can get through it. Usually, it’s just a matter of nutrition. Then you start off slowly again, and you pick yourself up and go.”

The nutrition problem for ultramarathon runners is largely a mathematical one. The human body can only digest around 7,000 calories of food per day — well short of the titanic energy demands of an ultramarathon. That leaves the athlete in a 13,000-calorie deficit for a 100-mile race run in 24 hours, and in a deficit of approximately 20,000 calories for a 150-mile race run in 36 hours. To make up the difference, the body is forced to tap into its reserves of stored fat and sugar, and it has to cannibalize muscle tissue, too.

The only way to delay exhaustion is to eat, a lot. And the way ultrarunners get their calories seems to be at odds with the healthy, pure lifestyle their sport espouses. Often running straight through the night, ultramarathon runners don’t have the luxury of stopping for whole meals. So, by necessity, they have to consume massive amounts of calories while on the run. The solution? They turn to food that has the most bang for its buck. And that often means energy-dense, processed sugars and fats.

Dean Karnazes, one of the sport’s few media icons, describes his unique method of fueling for long runs in his 2005 book Ultramarathon Man: Confessions of an All-Night Runner. According to Karnazes’ account, he has a pizza and an entire cheesecake from his favorite Italian restaurant delivered to a street corner in the middle of the night. He spreads the cheesecake on the pizza, then rolls up the extra-large pie like a giant burrito and shovels it all into his mouth without breaking stride.

Apart from these unusual eating habits, the physiology of ultrarunning champions is another of the sport’s unusual quirks. Most notably — a runner’s performance potential is not necessarily capped by age and sex.

“You get more stamina and endurance as you get older, but you won’t get more speed,” Cesario says. “In high school and college I used to run cross-country, and I remember I was running five-minute miles and all that. I’m certainly not doing that now. But when I was in high school and in college I certainly wasn’t doing 40-mile runs on the weekend just because I had the time. But now I can go farther. A little slower, sure, but I can get there. Whereas before, that wasn’t so.”

The ultramarathon distance also levels the playing field between men and women. In 2002 and 2003 an American woman named Pam Reed outright won the Badwater Ultramarathon, a 135-mile slog across California’s Death Valley, defeating some of the best male ultrarunners in the world. Athletes for Badwater are selected by invitation only, and the field typically includes some well-known athletes, such as former Navy SEAL David Goggins.

Californian Ann Trason broke 20 world records in her storied ultrarunning career. Along the way, she often beat some of the world’s best male runners in premier ultra events, including the Western States 100 and the Leadville Trail 100 in Colorado.

“I break it down into the physical, the mental and endurance,” Trason, who was a diminutive 105 pounds in her prime, told The New York Times in a 1996 interview. “Physical is the only gender-specific area; men have more muscle mass, the strongest man is always going to be stronger than the strongest woman. But I think the physical is only a small percentage of ultra. The mental part includes preparation, strategizing, problem solving. […] And you have to want it, you have to have the passion, you have to be willing to take risks. You can never be sure you’ll finish.”

6 a.m. — After 100 miles of running, Cesario begins to hallucinate. He is alone. Of the three athletes who started the race, he’s the only one still running. He wants to quit.

When the body begins to fail, it is the mind that carries ultrarunners to the finish line.

“I just try to get to the end,” Cesario says. “I figure if I stop, I’m going to remember that stop forever. But if I continue, I’ll always remember that I’d done it.”

Ultrarunners experience a fraction of the crowd support that normal marathon runners do. At best, they may reconnect with family and friends at aid stations. In the vast intervening voids, ultrarunners can find themselves alone for hours on end — often in remote wilderness. In this isolated state, as their bodies begin to buckle under the stress of the race, these extreme athletes find themselves drawing on instincts buried deep within the forgotten, primitive folds of their brains: a part of our species’ psyche into which we rarely tap during the day-to-day doldrums of modern life.

“That’s part of the challenge, you’re truly on your own,” Cesario says. “You’re working from aid station to aid station. And that’s how you keep going. You keep that positive mindset, instead of thinking, ‘Oh, I have another 80 miles to go.’ You go aid station to aid station.”

In 2007, the US Military Academy sanctioned a study on the psychological trait known as “grit.” It was an academic attempt to uncover what personality traits could identify the cadets most likely to quit during basic training. The study concluded: “General qualities possessed by high achievers included a strong interest in the particular field, a desire to reach a high level of attainment in that field, and a willingness to put in great amounts of time and effort.”

“Grit may be as essential as talent to high accomplishment,” wrote Angela Duckworth, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who co-authored the study.

If grit is essential to high achievement, then there is no doubt that ultramarathon runners have the right stuff. In fact, a 2018 clinical study by Australia’s Monash University found that ultrarunners actually experience less pain-related anxiety than the rest of us, as well as an “elevated pain tolerance.”

“It’s very hard in the beginning to understand that the whole idea is not to beat the other runners,” Cesario says. “Eventually you learn that the competition is against the little voice that says — no, you can’t.”

1:16 p.m. — After running 123 miles, Tony Cesario is done. He crosses the finish line in a time of 31 hours, 16 minutes. Then he collapses. When Cesario regains his senses, he immediately wonders: “Now what?”

So, once more we ask: Why?

Are ultrarunners an enlightened athletic caste that has uncovered suffering as the secret to happiness? Buddhist monks in the Himalayas are known to subject themselves to years of starvation and physical hardship to achieve enlightenment. Maybe ultrarunners are onto something.

Or maybe they’re just crazy — a hypercompetitive group of Type A personalities out to prove their athletic prowess in an arena more exclusive than that of regular marathons. Perhaps some are running from personal demons, or seeking an escape from depression. Some may just love to run.

Whatever one’s personal motivation may be, one thing is clear — there has to be a reason why. For, in the end, the true objective of ultramarathons is a threshold more elusive than any man-made finish line. The distance to this destination is not measured in miles or meters. Rather, it is measured in the pain it takes to get there. You see, the ultrarunner’s end goal isn’t the finish line, per se. It is to push the body to its breaking point — and then keep going. To find that moment when the mind summons its magical ability to push us beyond the chains of our genes.

“We’re most alive when we’re struggling,” Cesario says. “We think that comfort makes us happy. But instead of being comfortable, we’re lazy and miserable. There is magic in suffering.”

Joel says

Nice write up, thank you for it and for making me once again doing an ultra. Not in 2022, I already have a few other long distance races lined up. But I do want to earn a belt buckle some day.

Amelia says

You write so beautifully