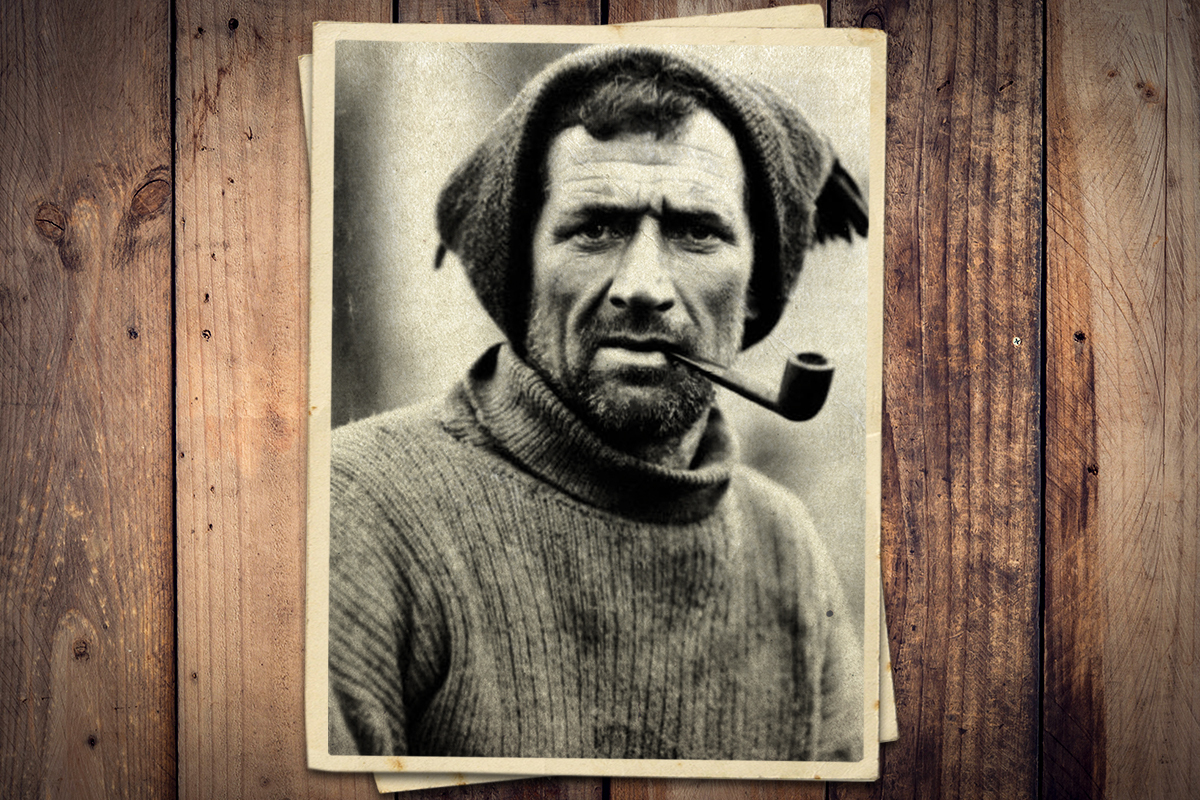

Rugged and tough, athletic and gritty, with a tobacco pipe clenched between his teeth, Tom Crean was the toughest Antarctic explorer you’ve never heard of. He spent more days in Antarctica than both Ernest Shackleton and Robert Falcon Scott. His crew mates called him the “Irish Giant” for his sheer size and strength, and despite his being one of the most experienced Antarctic explorers the world had ever seen, he wasn’t much for self-promotion and never earned proper international acclaim. Here are five things you need to know about this unsung hero of exploration.

He was a kid sailor.

Thomas “Tom” Crean was born in 1877 and raised on a farm near the village of Annascaul on the Corca Dhuibhne peninsula on the western side of Ireland. One of 10 siblings, Crean attended Catholic school in a poverty-stricken community until the age of 12 when he dropped out to work on his family’s farm. The stint was short-lived because only three years later he volunteered for the Royal Navy. He was so young he had to lie about his age to adventure out to sea. He eventually rose to the rank of petty officer after eight years in Queen Victoria’s fleet.

He saved his crew from a killer whale attack.

Between 1901 and 1904, Crean journeyed as a crew member of Capt. Robert Falcon Scott’s Discovery expedition. “Scott of Antarctica,” as he was affectionately called, was one of the most famous polar explorers in the world, and to be a part of his crew meant that one was a proven asset to the team. The team consisted of a who’s who of frozen adventurers including Ernest Shackleton, Frank Wild, William Lashly, and Edward Wilson. Crean participated in five major voyages with the Discovery and earned the crew’s respect for his brute strength in man-hauling equipment through the unknown territory and at minus 58 degrees, where no human had ever explored before.

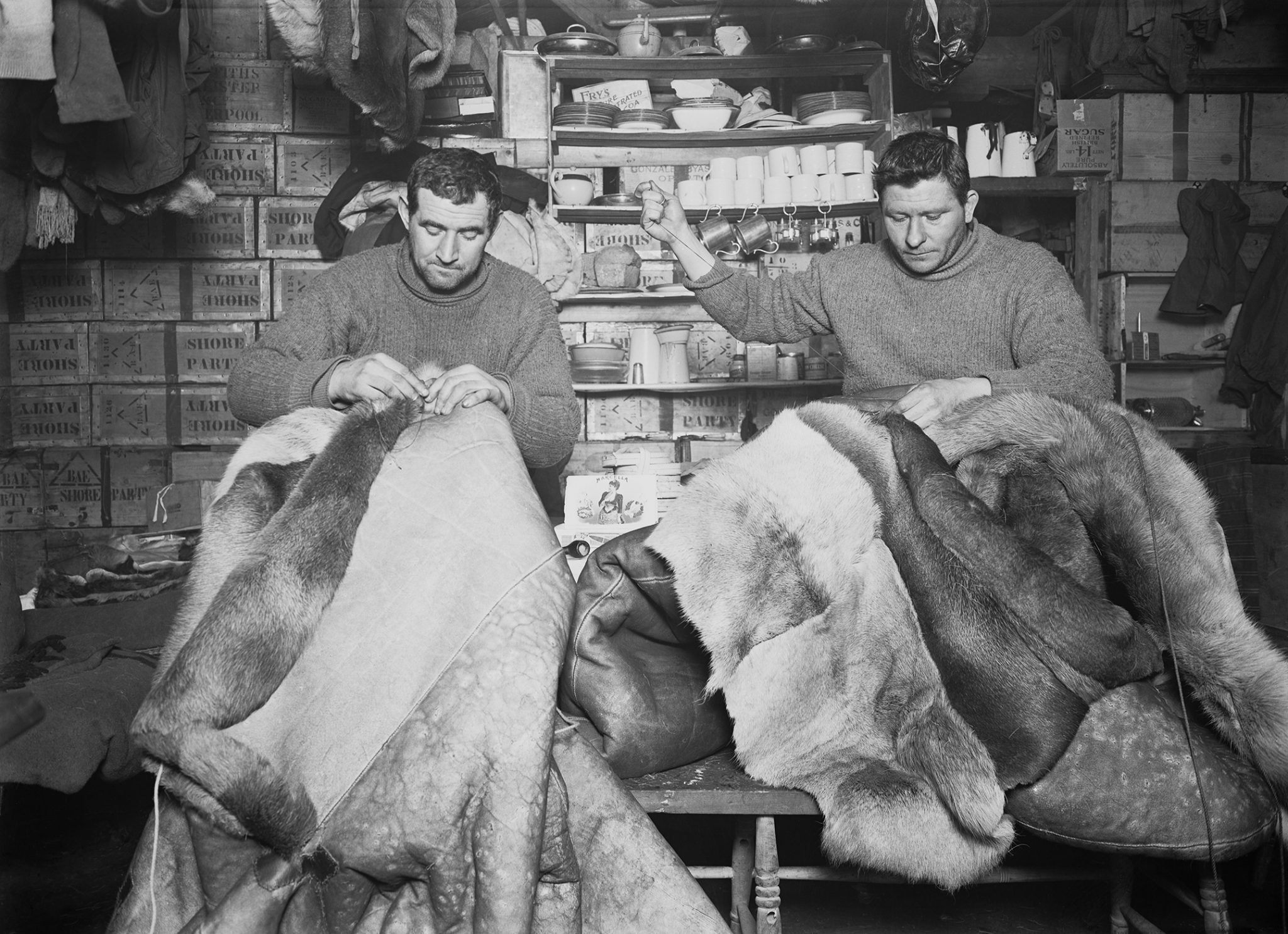

Following the Discovery expedition, Scott recruited Crean as his expert sledger and pony handler for the Terra Nova Expedition beginning in 1910. This meant he was in charge of the backbreaking job of hauling the equipment as well as keeping the ponies healthy on their voyage. Their mission was to lay claim to the South Pole, and Crean hauled tons of supplies across the ice to establish a supply depot along the route. Crean, Apsley Cherry-Garrard, and Henry Bowers narrowly escaped certain death after pitching tents on an unstable section of ice. The quiet night turned to chaos as the ice began to break beneath them and soon one of their ponies disappeared below the dark icy water. Their ice floe separated from their equipment, but Crean acted quickly, jumping from ice floe to ice floe while a pod of orcas splashed and stalked his every move.

He scaled an icy cliff and walked across the Barrier (today known as the Ross Ice Shelf) to get help. In November 1911, the journey to the South Pole commenced and consisted of three stages: 400 miles across the Barrier, 120 miles up a heavily crevassed Beardmore Glacier, and 350 miles to the South Pole. Crean had made it all the way to the final leg before reaching the pole when he, Bill Lashly, and Teddy Evans were ordered to go back mid-January 1912.

He hiked 30 miles in subzero temperatures on two biscuits and a chocolate bar.

On their 730-mile return trip Teddy Evans developed snow blindness along with a serious case of scurvy, and by February he couldn’t walk without support. Evans told Lashly and Crean to leave him behind, but the pair refused to abandon him. Pulling their equipment and Evans on a makeshift bed, they made it to within 35 miles of Hut Point, a four- or five-day journey away, to get help.

At the pace they were traveling, they wouldn’t make it in time to save Evans’ life. Instead, Lashly chose to erect a tent and stay behind with Evans, while Crean went forward alone and somehow reached the camp in a mere 18 hours.

“So it fell to my lot to do the 30 miles for help, and only a couple of biscuits and a stick of chocolate to do it,” Crean recalled. “Well, sir, I was very weak when I reached the hut.” Ultimately, a dog team returned for Evans and Lashly before a blizzard could seal their fate.

Although he saved the lives of these two men, in late October Crean joined a search party for the remainder of his missing team who hadn’t returned from the South Pole. He received the Albert Medal for bravery.

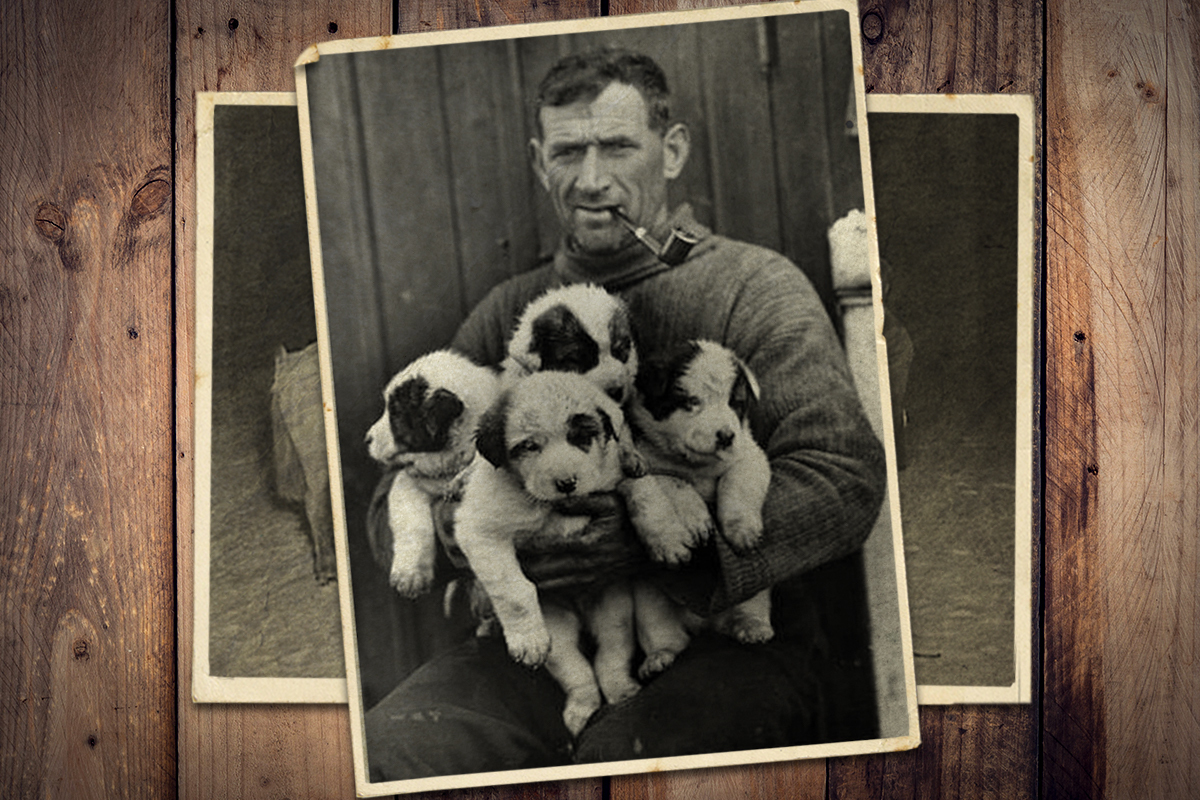

He loved dogs.

Believe it or not, Tom Crean spent more time in Antarctica than both Shackleton and Scott. Despite its being less than a year since he had returned from the icy and desolate continent, he accepted Shackleton’s offer to board the Endurance for the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. From 1914 to 1916, Crean was involved every step of the way, including filling a role as a puppy guardian for their sled dogs Sally and Samson. The four puppies were named Roger, Toby, Nell, and Nelson. Sadly, the 69 Inuit dogs on the Endurance expedition either died by disease or were shot.

He retired as an innkeep.

Three brutal Antarctic expeditions, personally saving the lives of 28 crew members, and the unsung hero of the greatest survival story in the world — Tom Crean returned to Annascaul, his childhood village, to start the South Pole Inn. He never gloated about his exploits to anyone. “He put his medals and his sword away in a box on a wardrobe and that was that,” said his daughter Eileen Crean. “He was a very humble man.”

The remaining 20 years of Crean’s life were spent at the South Pole Inn. He only told his stories to curious children. He mostly sat in the corner reading the newspaper while his wife, Nell, ran the pub. His pint of choice was Guinness, and the beer-maker later immortalized his legacy in an epic ad dedicated to his memory. Tom Crean passed away in 1938 at 61 years old.

Comments