Surviving a snake bite is all about knowing what you’re up against. Venomous snakes can be found in warmer climates all over the world. Of the more than 3,400 known species of snakes, about 600 of them are venomous, one-third of which pose a medical emergency.

For example, the king cobra can inject almost 1.5 teaspoons of venom into a human; that’s more than is needed to kill up to 20 people. Meanwhile, the Australian coastal taipan delivers 10 times the venom needed to kill a person. The black mamba, the death adder, and the diamondback rattlesnake are among the world’s deadliest snakes.

The World Health Organization estimates that around 5.4 million people are bitten by snakes each year, with just over half of those bites being from venomous species. About 125,000 people die, and three times that are afflicted with permanent disabilities like amputations, paralysis, blood disorders, and kidney failure. Though most of these fatalities occur in tropical areas due to the increased proliferation of venomous snakes in those regions, there are nearly 9,000 bites each year in the United States. The U.S. Poison Control data show that only one in approximately 736 bite victims will die each year.

The Effects of Venom

Statistically speaking, the largest threat of a venomous bite in North America comes from a rattlesnake; they make up 16 out of the 21 species of venomous snakes on this continent. A typical rattlesnake, for example, can strike from a distance of about one-half its length; doing the math, a 3-foot snake has an 18-inch strike radius. Its fangs can plunge about a half-inch into your skin. When bitten, you can expect pain, tingling and burning in the bite location.

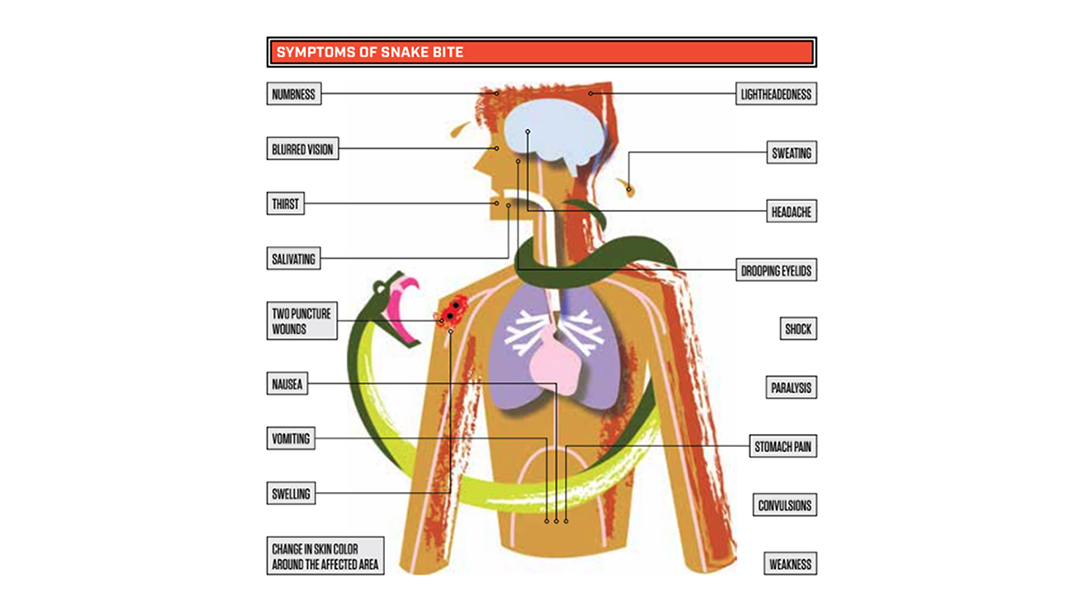

As soon as the rattlesnake venom enters your body, hemotoxic elements begin to damage tissue and affect the circulatory system by destroying blood cells and skin tissues and causing internal hemorrhaging. Rattlesnake venom also contains neurotoxic components that immobilize the nervous system, affecting the victim’s breathing and sometimes stopping it. Most rattlesnakes have venom composed primarily of hemotoxic properties. Baby rattlesnakes and the Mojave rattler are the exceptions; they have venom that contains more neurotoxic properties than hemotoxic, which makes them very dangerous.

Rarely, intravenous injection occurs. However, when it does, rapid onset of these symptoms occurs, which may send toxins farther along the bloodstream.

How to Treat a Snake Bite

The first thing you should focus on when helping a snake bite victim is acquiring medical assistance as quickly as possible, preferably in a hospital. Barring that, follow these helpful tips.

Do’s:

- Note the time of the bite and the type of snake.

- Keep calm and as still as possible.

- Remove any constricting clothing or jewelry around the bite area.

- Carry the victim.

- Wash the bite with clean water and soap.

- Keep the bite area lower than the heart.

- Wrap a bandage 2 to 4 inches above the bite to slow the spread of venom if medical help is more than 30 minutes away.

Don’ts:

- Don’t let the victim walk or move under his own power.

- Don’t use a tourniquet or a cold compress on the bite.

- Neither by mouth nor pump device, don’t cut into the snake bite or suck out the venom.

- Don’t give the person any meds unless directed by a doctor.

This story first appeared in Ballistic Magazine on Feb. 11, 2021.

Read Next: No Fences: Hunting Lions in Tanzania

Comments