This summer in the western United States hundreds of wildfires will ignite. Some of these fires will be many miles from the nearest road. Others will grow rapidly and require immediate reinforcement of the firefighters already engaged. In some cases, situations call for a higher level of leadership and experience to manage the fight.

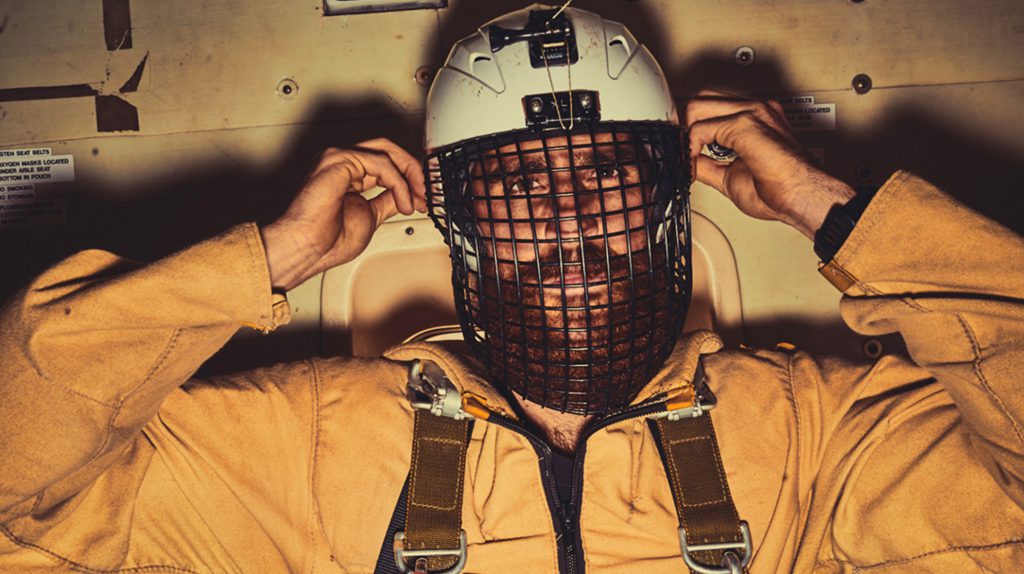

The wildland firefighters counted on at times like those possess the intelligence, decision-making ability, self-reliance, and physical fitness that make them the ideal choice in worst-case scenarios. They will get the call at their base, rig up in under two minutes, board a short takeoff, and landing aircraft, and parachute into the job site. They are the smokejumpers.

Smokejumpers will be the first to tell you they are a very small part of the national response “big picture,” and they just get to the fire in a manner different than anyone else. They’ll also humbly admit they do the same job as other firefighters once on the ground, but probably don’t work as hard as a hotshot crew!

The Jumpers

Parallels between smokejumpers and airborne units of the military are easy to draw, and both trace their techniques and operational heritage back to 1940. In that year on July 12, two firefighters for the first time parachuted in to get a foothold on a wildfire burning in the Nez Perce National Forest in Idaho. Five weeks later, the U.S. Army Parachute Test Platoon made its first training jump at Fort Benning, Georgia, on August 16.

Mike Haydon is a former smokejumper and currently the incident commander for the Rocky Mountain Type 2 Incident Management Blue Team. Mike attributes much of his leadership style and ability to make decisions under pressure to his time as a smokejumper.

Force Multiplier

Haydon also explained how as few as two smokejumpers with the right skills could be dropped alone on a fire, or a squad of eight highly experienced and widely cross-trained jumpers could join a large contingent already on scene and turn the tide of the battle. Hearing him talk about the “force multiplier effect” of smokejumpers, another more recent parallel comes to mind—when small numbers of Army Delta Force and Army Special Forces soldiers embedded with Army and Marine units during the second battle of Fallujah, Iraq, in late 2004.

Like those military special operations units, smokejumpers are looking for people with an undaunted mindset—those who believe they will prevail in the face of uncertainty. They want candidates who thrive in adversity and are eager to push themselves physically.

The right mindset and proper commitment are only the first steps of many toward becoming a smokejumper. Training begins years before a candidate first straps on the Paraflight DC-7 or Performance Design CR-360 ram air square parachute.

The Right Mindset

Being a smokejumper is a federal job, either with the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) or the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). It’s not unusual for a smokejumper trainee, one of the few selected from hundreds of applicants every year, to have ten years of previous wildfire experience. One type of experience they prefer you don’t bring with you is prior time under canopy—whether military or civilian.

The curriculum at the USFS and BLM jump schools includes rigorous physical training, teamwork evaluations, training on smokejumper equipment, safety and emergency procedures and, of course, parachute jumps into drop zones of increasing complexity from wind, terrain, and overall risk factors.

Intense Training

Successful completion of jump school may mean assignment to one of seven USFS or two BLM main smokejumper bases across the country, including Alaska. Both services also establish expeditionary “spike bases” at remote airstrips to improve response time. About 320 USFS and 150 BLM smokejumpers are on duty each fire season. Arriving at a base and joining a 20-person crew is only the end of the beginning of a smokejumper’s training. Each year the smokejumper community has attrition due in part to “unsuccessful rookies.”

Those who survive and thrive in the elite, small-unit atmosphere of a smokejumper crew live for the next fire. Smokejumpers are known in firefighting jargon as an “initial attack resource.”

Two minutes or less, in fact, is the time smokejumpers are allowed to don their padded jumpsuits, main and reserve parachutes, and have their helmets, gloves and personal gear bags in hand ready for buddy inspection. After suiting up, the jumpers form a circle and review emergency procedures, including chute malfunctions, mid-air collisions, and ground hazards.

Leadership and Command

En route to the drop zone, an experienced jumper known as the spotter functions in a way similar to a military jumpmaster. The spotter updates the jumpers with information from the pilots, assesses the best location to put jumpers out, provides any available updates on the fire, and gives all commands to prepare them to exit the aircraft.

Jump altitude is 3,000 feet above ground level. All aircraft exits using the DC-7 and CR-360 parachutes are from a seated position. Static lines connected to inside the aircraft deploy the drogue chutes and stabilize the jumpers who, after a “jump thousand, look thousand, reach thousand, wait thousand, pull thousand” ram air jump count, pull the drogue release handles on their harnesses, and deploy their main parachutes.

After their main chutes open, jumpers check their canopies, the airspace around them for other jumpers, and gain canopy control. From there, it’s driving the chutes to their selected drop zones or, in some cases, the trees themselves. Upon landing, smokejumpers cache their jump gear, shoulder their packs, and head toward the fireline to get to work. Sounds exciting and a bit on the edge, right?

Making The Cut

Rookie training is designed to prepare smokejumper candidates with the necessary mental fortitude, logic and reasoning skills, and physical capacity to succeed in highly dynamic and arduous work environments. Training lasts a minimum of 6 weeks and only a small group of people each year will make the cut. Rookies must be in excellent physical shape and pass the PT test on the first day of training. The minimum standards are as follows:

- 7 Pull-ups

- 25 Pushups

- 45 Sit-ups

- 1.5 mile Run in 11 minutes

- 110 pound pack out: 3 miles in 90 minutes

- 45-pound work capacity test: 3 miles in 45 minutes.

Rookies are evaluated on team attitude, ability to learn, and performance. Due to the large amount of information and field exercises that need to be completed, candidates should expect long days. If during the training it is determined that a rookie cannot perform the job, they will be dropped.

Field exercises provide the skills needed to manage the diverse situations encountered during smokejumper operations. They include tree climbing, cross-cut and chainsaw use, map and compass, mock airplane exits, landings, and leadership exercises.

Making The Grade

Before candidates are allowed to make their first practice jump, they must successfully pass courses in pre-jump aircraft procedures.

Rookies need to complete 15 practice jumps into a variety of spots, which increase in difficulty with each successful jump.

Individuals chosen for this position are based on their abilities, character, and proven performance. It is an opportunity that very few people get. If you think you have what it takes, visit USAjobs.gov and search for an open announcement. (source: fs.usda.gov)

This photo first appeared in Skillset Magazine on Oct. 20, 2020.

Read Next: Meet Cal Fire’s Pranay Manghirmalani

Comments