For many people, their exposure to classic literature has been limited to what was shoved in front of them during high school or college. Some of you may have soaked up these novels at the time, but a lot of us breezed through them without taking the time to understand the depths of what the author was trying to convey.

Now thanks to COVID-19, social distancing, and shelter-in-place orders, many of us are holed up in our homes with nothing but time — and maybe some anxious thoughts about work, our children, and, of course, a global pandemic. But if you’re looking to pass the time and have been meaning to catch up on a few classics, here’s a good list to get you started.

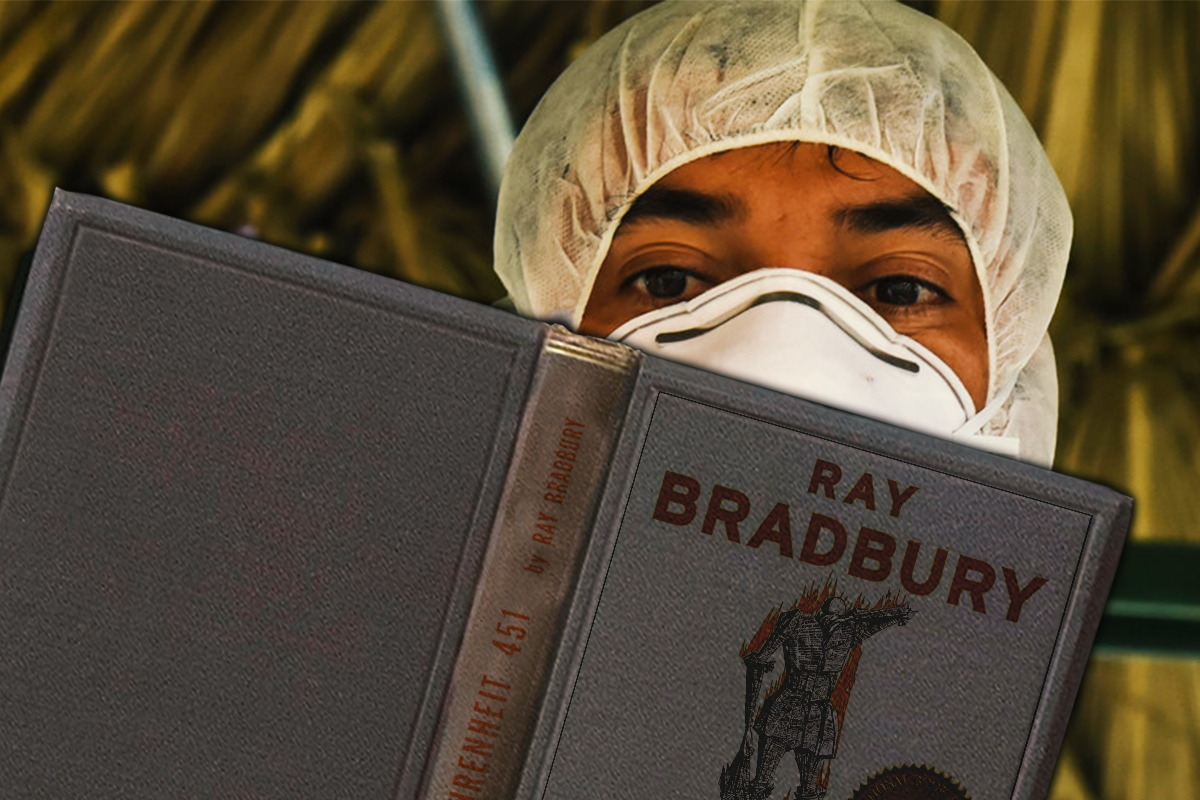

“Fahrenheit 451” by Ray Bradbury

Out of all the books read in high school, this one often stands above the rest — on top of being a timeless classic, it’s actually quite entertaining on a surface level. Bradbury’s writing is easy to blast through, yet it somehow feels like poetry.

No matter how you absorbed the classics in high school or college, re-reading them as full-fledged adults is an entirely new experience. In this instance, the big takeaway many remember is often a simple “burning books is bad,” or even “censorship is bad.” These are common themes throughout, but they are only the start.

At its crux, “Fahrenheit 451” is about the endless bombardment of mindless information and factoids overwhelming any profound thought or idea that might not match up with the status quo. Of course, this is relevant to us now more than ever, as we are living in the middle of the information age.

One of the characters explains to Montag, the protagonist, “It’s not books you need, it’s some of the things that once were in books. The same things could be in the ‘parlour families’ (a form of futuristic reality TV) today. The same infinite detail and awareness could be projected through the radios and televisors, but are not. No, no, it’s not books at all you’re looking for! Take it where you can find it, in old phonograph records, old motion pictures, and in old friends; look for it in nature and look for it in yourself. Books were only one type of receptacle where we stored a lot of things we were afraid we might forget. There is nothing magical in them at all. The magic is only in what books say, how they stitched the patches of the universe together into one garment for us.”

Burning the books is not what is inherently wrong — it’s burning the books because they cause a “bother.” Censorship restricts all bothersome things, forcing the people to fall in line without access to volatile information.

It’s a beautiful book, as profound as it is exciting.

“All Quiet on the Western Front” by Erich Maria Remarque

If “Fahrenheit 451” is enjoyable, “All Quiet on the Western Front” is the opposite — dark, heavy, and heartbreaking. The novel follows a German soldier in World War I, a young man who was shipped off to war before he was 20 years old, fighting because of politics he does not understand.

While it’s not difficult to read on the technical side, “All Quiet on the Western Front” is emotionally devastating. It illustrates just how brutal the Great War really was, how not every German was an evil, mustache-twisting villain, and how a war of that magnitude can crush the soul of entire generations. It also dives into some harrowing facets of the war itself — the death and serious wounds of countless friends, the gas and the bombardments, what it’s like to be stuck with a slowly dying, injured man in a crater for hours, the sheer disappointment of realizing you’re fighting for something you don’t believe in — just about every page is gut wrenching.

This novel wasn’t written by some high-brow author who lived a world away from combat and conflict. It was written by Erich Maria Remarque, a German man who was conscripted into the army during World War I at the age of 18. He was seriously wounded by shrapnel in his leg, arm, and neck, and spent the rest of the war in recovery. This story is so saturated with dark truth, it’s no surprise that it comes from a man who experienced it firsthand.

For example, one of the iconic scenes of the book is when they are bunkered down and are forced to hear the anguished cries of wounded horses:

Things become quieter, but the cries do not cease. “What’s up, Albert?” I ask.

“A couple of columns over there got it in the neck.”

The cries continued. It is not men, they could not cry so terribly.

“Wounded horses,” says Kat.

It’s unendurable. It is the moaning of the world, it is the martyred creation, wild with anguish, filled with terror, and groaning.

We are pale. Detering stands up. “God! For God’s sake! Shoot them.”

He is a farmer and very fond of horses. It gets under his skin. Then as if deliberately the fire dies down again. The screaming of the beasts becomes louder. One can no longer distinguish whence in this now quiet silvery landscape it comes; ghostly, invisible, it is everywhere, between heaven and earth it rolls on immeasurably. Detering raves and yells out: “Shoot them! Shoot them, can’t you? Damn you again!”

“They must look after the men first,” says Kat quietly.

Most modern, young combat veterans haven’t experienced a war like this, but they may have experienced just enough for the book to resonate with them. “All Quiet on the Western Front” might break your heart, but everyone should read it.

“The Open Boat” by Stephen Crane

This novella is a breeze to read through — it’s short, to the point, and quite moving. It follows four men who are stranded on a dinghy after their ship has sunk. Pitted against the elements, they struggle with their sanity and work together to survive.

If you were to pick up this book, you might find that it rings with an air of authenticity, sort of like “All Quiet on the Western Front.” There are aspects of it that just seem a bit too real to be made up.

While the characters are fictitious, Stephen Crane was actually a survivor of a real shipwreck. He was really stranded on a dinghy with a few others, and the way he describes the whole ordeal is (at times) disturbingly realistic and elegant at the same time. From the way he describes Mother Nature as being as cruel and indifferent as she is beautiful to the way he feels his own death and how it would simply wash away with nature like everything else — it’s a haunting novella.

Realism is important to many readers, but it is especially important to veterans. This passage, born from Crane’s own memory, illustrates how it resonates with the veteran crowd in particular:

“It would be difficult to describe the subtle brotherhood of men that was here established on the seas. No one said that it was so. No one mentioned it. But it dwelt in the boat, and each man felt it warm him. They were a captain, an oiler, a cook, and a correspondent, and they were friends—friends in a more curiously ironbound degree than may be common. The hurt captain, lying against the water jar in the bow, spoke always in a low voice and calmly; but he could never command a more ready and swiftly obedient crew than the motley three of the dinghy. It was more than a mere recognition of what was best for the common safety. There was surely in it a quality that was personal and heartfelt. And after this devotion to the commander of the boat, there was this comradeship, that the correspondent, for instance, who had been taught to be cynical of men, knew even at the time was the best experience of his life. But no one said that it was so. No one mentioned it.”

“The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe” by C.S. Lewis

“Isn’t that a children’s book?” It certainly is. It’s an adventure wherein four children crawl through a wardrobe into the magical land of Narnia, filled with evil witches, talking animals, spells of winter, and fantastical creatures.

However, there is another way to view this book. Between the jolly talking beavers and the cackling witch lie some very serious undertones about war and violence.

Like his dear friend J.R.R. Tolkien, Lewis was a World War I veteran. He fought in the Battle of the Somme, which, to give you some context, meant he was part of a battle where the British suffered 420,000 casualties — more than 57,000 of them on the first day. Lewis was 19 at the time.

There are elements of war and violence woven into all of Lewis’ fiction, including “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.” Weapons are deliberately described as tools, not toys, in a fairy tale that could easily romanticize magical bows and swords. A good portion of the book is dedicated to walking (as is a good portion of war), monotonously moving forward until the characters begin to reach that altered state of consciousness with which anyone who has been on a long ruck march is familiar.

One of the most striking moments is when Peter, the eldest son who was gifted the sword, has to confront an evil wolf. This could have been described as a fun fight where the protagonist overcomes the enemy and returns to his friends in triumph — but it does not go how Peter imagined. Read this passage through the eyes of a 19-year-old C.S. Lewis in the trenches at the Somme. Read it as someone who had preconceptions about combat and found themselves stumbling through it, clumsy and distraught, only to finish the deed by feeling “tired all over.”

“Peter did not feel very brave; indeed, he felt he was going to be sick. But that made no difference to what he had to do. He rushed straight up to the monster and aimed a slash of his sword at its side. That stroke never reached the Wolf. Quick as lightning it turned round, its eyes flaming, and its mouth wide open in a howl of anger. If it had not been so angry that it simply had to howl it would have got him by the throat at once. As it was — though all this happened too quickly for Peter to think at all — he had just time to duck down and plunge his sword, as hard as he could, between the brute’s forelegs into its heart. Then came a horrible, confused moment like something in a nightmare. He was tugging and pulling and the Wolf seemed neither alive nor dead, and its bared teeth knocked against his forehead, and everything was blood and heat and hair. A moment later he found that the monster lay dead and he had drawn his sword out of it and was straightening his back and rubbing the sweat off his face and out of his eyes. He felt tired all over.”

“Animal Farm” by George Orwell

American life is completely inundated with politics these days. The internet has given us infinite access to countless opinions splattered across the web, every single day. So why would anyone want to read another book about politics? Because it’s not the politics many of us are tired of, it’s the repetitive soundbites, the predictable, baseless arguments, and the memes that snarkily reduce an entire argument to a pathetic catchphrase — that’s what wears on the soul.

This is a short, easy read. Many of us read it as children, but rest assured, it’s not for children. It’s a complicated look at government and power, boiling it down to its most base elements and showing the reader why corruption and politics so often go hand in hand.

“Animal Farm” is set on a simple English farm and follows a group of oppressed animals who rise up and take control of the farm for themselves. The rebellion is led by two intelligent (literal) pigs, Snowball and Napoleon. You’ve probably heard some form of the joke, “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others” — this is where it originates.

While on the subject of equality, this speech from the book (defending the actions of “Comrade Napoleon”) gives insight into the book’s tone and direction:

“No one believes more firmly than Comrade Napoleon that all animals are equal. He would be only too happy to let you make your decisions for yourselves. But sometimes you might make the wrong decisions, comrades, and then where should we be?”

This is the sort of book that may have had one intent or another, and it may be interpreted one way or another, but it benefits anyone to read and ponder for themselves. No doubt, discussions on this book would likely be more fulfilling and productive than the latest buzzword argument on Facebook or Twitter.

BONUS (for the literature and war nerds): “The Epic of Gilgamesh”

This book is short, but it is neither an easy read nor is it a simple, coherent story that one can follow in the same way you can follow the books listed above. However, being that it’s literally the oldest surviving recorded story in history, it’s an important part of literature and just so happens to star a great warrior.

The story follows the exploits of King Gilgamesh and eventually Enkidu, a man wrought from nature, created by the Gods with the intent to stop Gilgamesh from his oppressive rule. The two of them wind up becoming great friends and going on adventures together. Like many older myths and stories, there are several different narratives, each worthy of individual examination, and then together as a whole.

However, one narrative that stands out from the rest is when Enkidu dies after a battle with the Bull of Heaven. Gilgamesh mourns his fallen brother deeply:

“He touched [Enkidu’s] heart but it did not beat, nor did he lift his eyes again. When Gilgamesh touched his heart it did not beat. So Gilgamesh laid a veil, as one veils the bride, over his friend. He began to rage like a lion, like a lioness robbed of her whelps. This way and that he paced round the bed, he tore out his hair and strewed it around. He dragged off his splendid robes and flung them down as though they were abominations … Bitterly Gilgamesh wept for his friend Enkidu; he wandered over the wilderness as a hunter, he roamed over the plains; in his bitterness he cried, ‘How can I rest, how can I be at peace? Despair is in my heart. What my brother is now, that shall I be when I am dead.’”

While the expression of grief has changed (we don’t exactly tear out our hair or rip up our clothes these days), the grief itself is all too familiar. There is power in reading this with the understanding that the bond of brotherhood, forged in combat, is so transcendental that it appears in strength in a story written thousands of years ago.

This article was originally published April 2, 2020, on Coffee or Die.

Comments