Chunks of ice break free from about 70 feet above, clacking off lower bulges before landing in heavy, dull thuds on the snow-buried slope only feet away.

“Ice!”

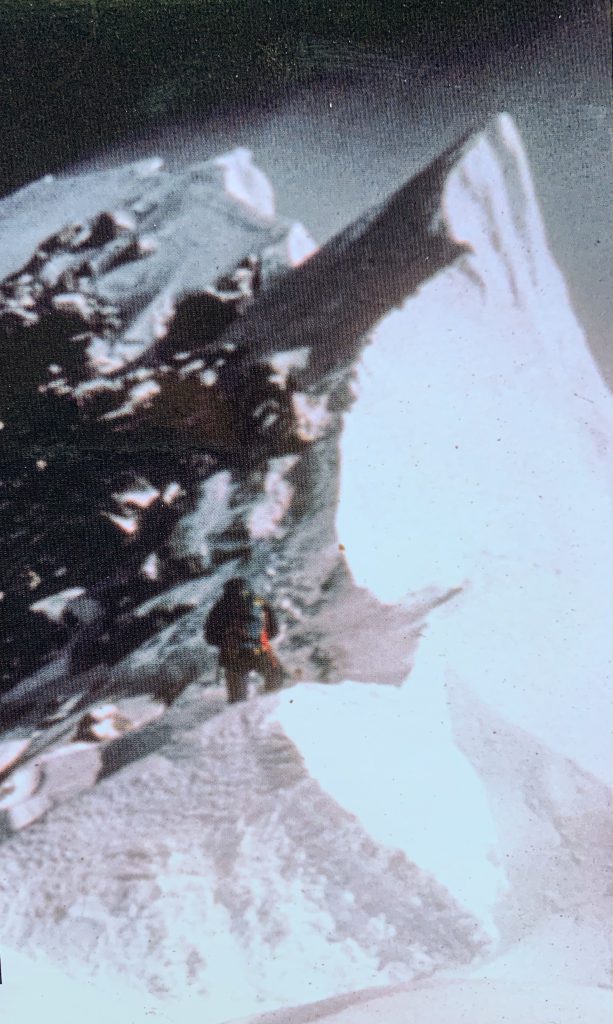

The climber that yelled down is pegged to the face of the wall by two ice axes and oversized spikes extending from the toes of his boots. An orange climbing rope anchored by his climbing partner at the top and attached to the carabiner on his harness trails lazily down the ice face below him.

“That’s why we wear helmets,” says Nick Yardley, a veteran climber, instructor, and mountain rescue team member. People have had their faces punched in by these frozen missiles. “Best not to look up.”

Yardley will be on “the sharp end of the rope” today, or the lead. Rick Wilcox, the reason for today’s climb, will follow Yardley’s lead up the face.

Wilcox is one of the most accomplished and influential American mountaineers that you’ve probably never heard of. But to anyone from the Eastern US climbing world, he’s immediately recognized as the godfather of New England mountaineering, “The Wizard,” or “The Legend.” Hundreds of professional guides and instructors across the country credit their start to Wilcox’s mentorship.

Yardley has emptied his pack and is busy organizing ice screws, carabiners, and a belay device on his harness. A 200-foot lime-green climbing rope is bound neatly and sits on top of his pack. For him and Wilcox, the routine is rote.

Everything has its place and specific order to match the climb ahead. Efficiency is vital during an ascent. Fatigue can set in quickly if you’re expending too much energy fighting with gear on every anchor and hookup. And fatigue leads to failed attempts — or worse.

Even with their decades-long friendship and dozens of Himalayan climbing expeditions and countless mountain rescues with the North Conway Mountain Rescue Service made together, this will be the first time that the two men have climbed ice on the same rope.

Looking up at the ice, the men agree on a multi-pitch route. “Nothing crazy,” says Yardley.

Northern New Hampshire is considered a mecca for ice climbers around the world, and Crawford Notch is one of the reasons. With roughly 100 climbs in the park, it is a year-round playground for climbers of all experience levels. But when winter freezes this sleepy, unassuming region to its core, some of the most technical, confidence-rattling, and sought-after ice in North America comes to life.

Today’s plan is to climb Chia, a 4+ rated, 150-foot-tall mass of topaz-blue-tinted ice within the Amphitheater section of Frankenstein Cliff in Crawford Notch State Park.

In the ice climbing world, each established route in North America has a rating based on how technical it is: Grade 1 being a low-angle climb requiring basic expertise and Grade 6 sporting long sections of vertical ice with some overhangs and free-hanging daggers. Think semi-steep, icy sledding hill versus a yodelayheehoo into an abyss.

Wilcox explains while double-checking that his crampons, the spikes attached to the sole of a climber’s boots, are ratcheted tight.

“The only difference between the Chia Direct, which is a 4-plus, and a 5 or 6 is the length of the column,” he says. “Over in Vermont, like Willoughby, and over in Canada, there’s a few places where they get up to 600 feet. And that’s a pretty sporty route. Even for the good guys.” But there are high-rated shorter routes in the area here as well that have the potential to grind accomplished climbers to a frustrating halt.

Yardley starts his run at the ice. “Climbing!”

Wilcox responds: “On belay!”

Wilcox served as the head of North Conway Mountain Rescue Service for 40 years, from 1976 to 2016. He was the second of only three presidents in the history of MRS. “I’ve sort of stepped out of mountain rescue a little bit,” he told Free Range American. “I’m still on the board though. We did 600 rescues during my 40 years.” You have to be more than just good at climbing to lead for that long — another reason his reputation is almost considered mythical.

Almost to prove the point, his presence in the Amphitheater sends some sort of signal or energy that every climber in the area senses even without seeing him.

A climber on belay on an adjacent route reports up to his partner. “It is Rick! Told you he was here.”

Read Next: Nepalese Team Edges Out American O’Brady for Historic 1st Winter Ascent of K2

Now 73, Wilcox was part of American climbing’s heyday, when every New England rock face and ice wall was still pristine and men like Warren Harding, Yvon Chouinard, Ray Jardine, Royal Robbins, and Earl Wiggins were pioneering routes in the Yosemite Valley.

This was a time when research and development of climbing tools was happening while they climbed, and guys like Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia, and Jardine were literally forging their equipment like blacksmiths would horseshoes. With roots in Lewiston, Maine, Chouinard would make an annual visit to Wilcox’s climbing school in Conway, New Hampshire, from his home in Southern California to put on a clinic with his new gear.

Today, Yardley sets a half-dozen anchors in the ice along the route, threading the rope through each and cinching it, and himself, to a tree at the top. Wilcox reaches the first anchor and buries the ice-axe points into the wall next to him. The toe spikes hold his feet steady as he frees the rope, unclips the carabiner from the anchor and locks it on the D clip on his harness, then backs the ice-screw anchor out of its hold.

Two scraggly-bearded guys in hard-worn climbing pants, sweatshirts, and helmets, carrying full packs, walk down the trail next to the tower of ice.

“Hey, you got the Legend out!”

“Ahhh, the Wizard! Nice.”

Wilcox has summited dozens of 7,000-meter peaks — 21,000 feet or higher — with five of them over 8,000 meters (24,000 feet). He’s guided more than 60 expeditions to some of the most storied mountains in the world from Alaska and Africa to Nepal and Chile. He led the first American team made up of only New England-based climbers to the summit of Mount Everest. And the first ascents of countless rock and ice climbing routes in New England have his name on them. So does the guidebook, The Ice Climber’s Guide to Northern New England, now in its fourth edition, which he co-wrote in 1972.

A picture of an older edition’s cover appears on page 27. “We climbed with strap-on crampons, leather boots, wool knickers, straight shafts not ice axes, no helmet, on a drop line,” Wilcox noted.

“At that time, there were very few climbers in New England. I was the worst-best at rock climbing, and worst-best ice climber in the valley,” he recalled with a laugh. “I was just keeping up with everybody. But there were almost no high-altitude climbers in this area.” That was something Wilcox discovered he had a passion for and well-tuned physiology to match.

“I started rock climbing when I was in high school with the Boston Appalachian Mountain Club chapter. When I went to the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, I got involved with some guys who ice-climbed and rock-climbed and did more and more of that,” he said. “My junior year, I got invited on an expedition to Alaska, with a group of climbers from that area, and we climbed the ninth-highest peak in North America, Mount Bona. Bona is 16,000 feet.” [Editor’s note: Summitpost.org lists Bona as the 10th highest.]

“There were around 10 people on the trip and I did better than anybody else with acclimatization, or how your body adapts to the altitude. Pretty soon, instead of being the only kid on the trip who hadn’t been on an expedition, I was leading the troops.”

Two-thirds of the way through the climb, another pair of climbers, a man and a woman in their late 50s, decked out with what looked to be brand-new boots, one-piece climbing suits, helmets, axes, and crampons, come down the trail.

“There he is. Man, that guy is just awesome.”

“Looking good, Rick!”

After college, Wilcox’s first job was at the Arctic Institute of North America, a military research station on Mount Logan, the second-highest peak in North America (19,541 feet) behind Mount McKinley (20,310 feet).

“I lived at 17,500 feet for two months studying high-altitude physiology,” he said. “I didn’t join the Army, but I was with them doing research on people who get really sick at altitude, which never happened to me. I was able to summit Logan, an early ascent of it, with some of the guys that were there.”

After his time on Logan, Wilcox spent about a decade with Eastern Mountain Sports as a rock- and ice-climbing guide and store manager, running trips to Peru, Alaska, and Europe, and climbing big walls in Yosemite. In 1979 he bought International Mountain Equipment from friends of his for $13,000 and expanded his guided trips to include the Seven Summits — the highest peak on each of the seven continents.

The Himalayas grabbed hold of him and wouldn’t let go. “I always wanted to climb Everest, which is 29,000 feet,” he said. “Always thought the phone would ring and it would be somebody saying we have an all-expense-paid trip, just join the group. Didn’t happen.”

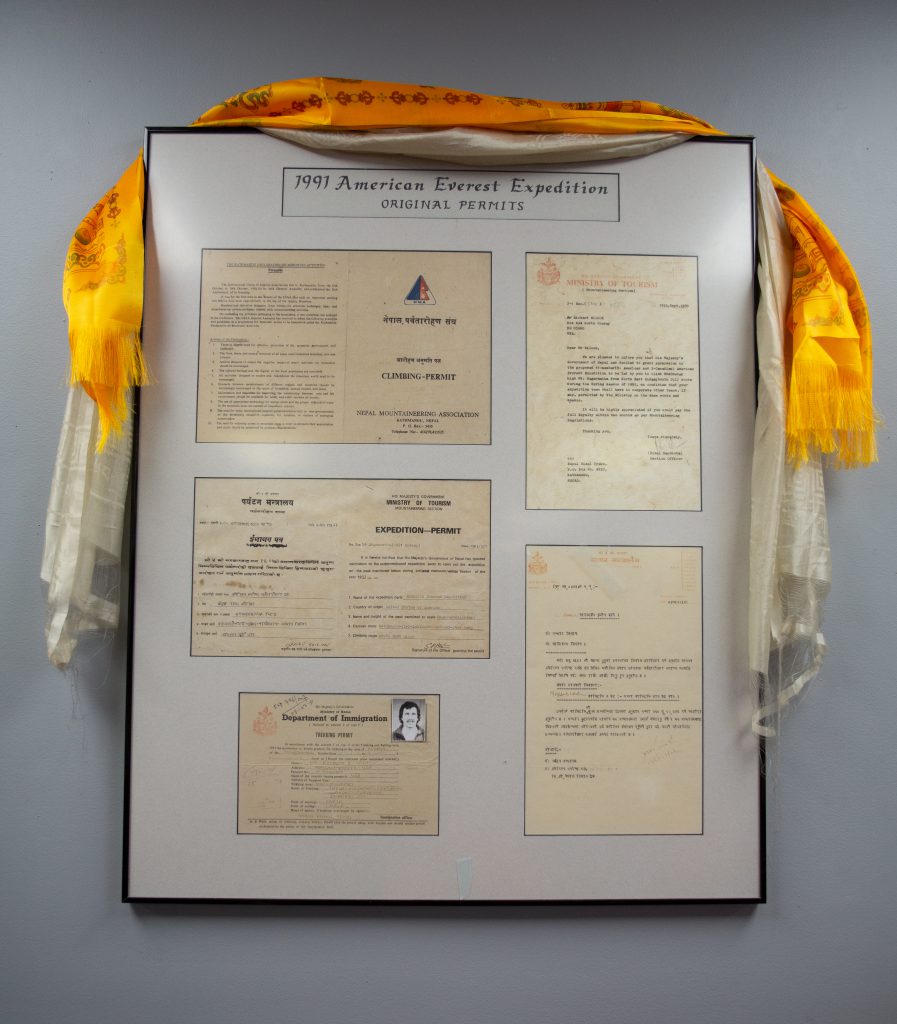

“So I put together a group of eight climbers. Our trip in ’91 was the first-ever Everest expedition to summit with strictly East Coast climbers, most of them from right up here in New England.” Wilcox was just the 260th climber to summit Everest. To date there are more than 4,000 on that list, with 500 attempting the climb each year.

At one time, Wilcox had stores in Portland, Maine; Salt Lake City; and New Hampshire. He’s since pulled back to the single location on North Mountain Highway in North Conroy, where the business continues to thrive. The store is base camp for a new generation of climbers. Of course, his employees are some of the most accomplished and humble leaders of the new school.

Wilcox crests the top of the wall, digging his ice axes into the packed snow to pull himself up. He walks the rope away from the edge and hugs a tree. Catching his breath and smiling, he looks back toward the wide-open valley beyond the cliff.

“She’ll go,” he says quietly.

As much as he’s defied both age and elevation, in true expert climber fashion, Rick Wilcox embraces the variables in his route.

“I’m in the process of getting out of the climbing school a little bit and the business,” he said. “I own the building, so I can be the landlord of the two businesses here and still run the travel business. I don’t know who will take them over. There isn’t the right person to do it yet. Maybe they will come along, maybe they won’t. I’m not worried about it.”

Read Next: The Triumph and Tragedy of K2’s Epic Winter Season

Comments