A lot of people think of beadwork as being the quintessential Native American decorative art, but long before Europeans brought glass beads to these shores, tribal artists were crafting beautifully decorated clothing and objects. The media they worked with for hundreds of years were porcupine quills. Using these stiff, hollow hairs, native quill workers created a dazzling variety of designs. This is the story of a quill master.

Quill Master Shawn Webster

Quill workers largely switched to using glass beads when they became widely available, in the 18th and 19th centuries, because the working techniques were similar but beads were less grueling to work with. Due to easier care than objects embroidered with quills, beads gained quick popularity. In some areas, however, the traditional methods stayed in use.

The Micmac and the Chippewa tribes in particular held fast to the traditional medium. Today, there is something of a revival of porcupine quill embroidery thanks to reenactors and living historians. Shawn Webster is one of the modern masters of porcupine quill embroidery. The quillwork Shawn is doing today rivals the finest work by native artists in the 18th century.

Quilling To Learn

Shawn’s foray into his craft began the same was as many others. As a young man, he attended a rendezvous and saw a quill-embroidered item for sale. He liked the piece, but he couldn’t afford the $50 price tag. So, naturally, Shawn decided to learn how to make one himself. There are countless pieces of gear in my kit that I created for the same reason. The difference is, for Shawn, it became his life’s work.

Shawn’s interest in Native American crafts grew out of his work. For five years, Shawn taught high desert survival at the University of Southern Utah. He believed that the best survivalists who ever lived were Native Americans and the frontiersman who learned from them. He wanted to learn their skills and recreate their way of life in the wilderness.

Since he lived in Utah, Shawn’s interest naturally gravitated to the Rocky Mountain fur trappers, the mountain men. Shawn even taught himself to trap beaver using hand-forged traps, and he started quill working. Not one to shy away from a challenge, Shawn is entirely self-taught; finding that he had a lot to learn. Quilling is a much more complex process than bead-work embroidery.

First there is the matter of the quills themselves. Not all porcupine quills are suitable for quillwork. Quills that work well are 2 to 3 inches long. Before dying, the quills are an off white color with black tips. The tip of the quill is where the barb is. Prior to use, the barbs must be removed. Dying the quills often takes place before the barbs are removed.

Dying quills is an art in itself. Quills are difficult to dye, and Shawn prefers to use natural dyes that he prepares himself. It isn’t easy but the results are worth the effort. Dyed quillwork adds vibrant color to leather items that would otherwise look bland.

Soaking the quills before use makes them pliable and easily flattened. As Shawn discovered, soaking too many quills at one time will cause them to dry out before you get to them. If the quills dry out before you use them they will need to be re-soaked.

Chance Meeting

When he started as a quiller, Shawn was trying to recreate the quillwork he was seeing at rendezvous, but a chance meeting in 1985 changed everything. While riding horseback to an American Mountain Men rendezvous, in Wyoming, Shawn met David Wright, also riding to the rendezvous. They struck up a strong friendship on the trail that has lasted for three decades.

Best known for his depictions of the early American frontier, David Wright is a world-class artist. He is also a top-notch photographer who has developed an extensive photographic collection documenting Native American objects. After the rendezvous, David sent Shawn 500 photographic slides, all high-quality images of original Native American quillwork. By studying those slides closely, Shawn was able to raise his art to the next level.

I first encountered Shawn’s quillwork years ago, when I saw a picture in a magazine of one of his most famous designs, the Metis coat. Today, the word “metis,” with a small “m,” is the accepted word in Canada for people of mixed Native American and European ancestry. The capitalized version of “Metis” refers to a government-recognized, indigenous cultural group—or a tribe if you will—that evolved out of generations of metis people.

From the earliest days of Canada, the French fur traders and voyageurs intermarried with native women. Their children often identified culturally with their mothers’ tribes, and many of these metis offspring followed their fathers into the fur trade.

In the early and mid-19th century, as the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Northwest Company’s fur-trading operations pushed across Canada’s western plains, metis employees formed the experienced back-bone of the trade. By then, most metis children had been born to families where both parents were of metis ancestry. They no longer identified with their grandmothers’ tribes and the Metis culture began in earnest.

Colorful Tradition

Shawn’s Metis coat reflects the melding ried with native women. Their children of cultures that created the Metis. Closely tailored, with cuffs and lapels, the coat reflects its European counterparts. Made of two-tone, brain-tanned elk hide, the coat required three cow elk skins. Shawn smoked the darker hides in a cottonwood fire. Soaking the lighter colored panels with willow wood gave them a creamy color.

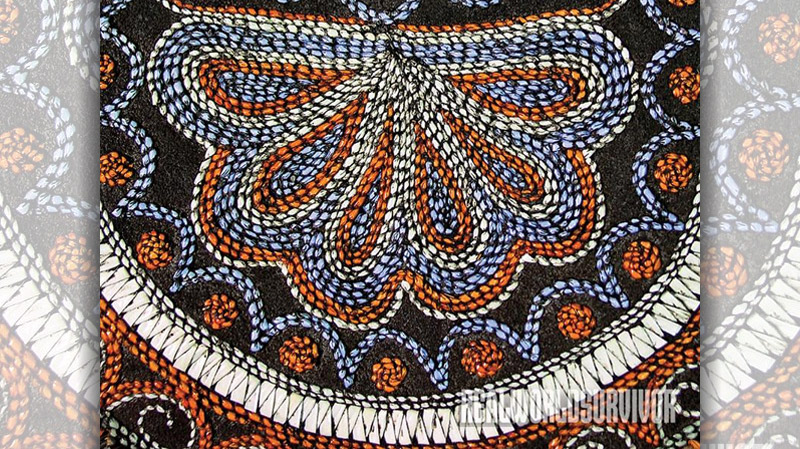

The decorations on Shawn’s Metis coat replicate the actual quillwork on a Sioux Metis coat that is on display in the Denver Art Museum. Decorated with graceful quillwork, in a combination of floral and geometric designs, the Matis coat combines the zigzag quilling technique with single-line quill embroidery. All of the leather fringes on the coat are wrapped together in pairs by quillwork bands. Additionally, all the coat’s quills are beautifully dyed in hues of red, yellow and blue.

Those colors, and all the colors that Shawn uses, are the result of 35 years of experimentation with different plants and minerals to create the colors, and then many more hours of trial and error to find the right mordant for each color to ensure permanent color saturation on the quill. Shawn said it took him 17 years to get a really good handle on natural dyes and mordants. Even after 35 years, he is still learning.

From Quills To Rifles

He may still be learning, but there is no doubt that Shawn is already a master at his craft. One of Shawn’s quill-decorated bags replicates a bag in the Ottawa Museum of Civilization. This Huron-made masterpiece dates to 1829. Shawn’s version is eye-popping. The predominant color is a vibrant orange. There is orange quillwork and a really stunning orange border made of dyed deer tail hair secured in tin cones. Shawn handmade all 110 tin cones. He achieves the bold orange color by dying the deer hair and quills in a combination of ground cochineal beetles mixed with Osage orange wood dust. The delicate, blue-colored quills were dyed with indigo.

Shawn has done a lot of work in the Huron floral style. He speculates that the Huron style was based on conventions used in European embroidered tapestries. Huron women picked up their designs from Ursuline Sisters, who were sent from France as missionaries. The native women translated the work done by the nuns in silk thread to designs of their own, embroidered with quills.

Along with bags, knife sheaths are also excellent vehicles for quillwork decoration. Shawn’s knife sheaths will knock your socks off, as evidenced by a pair of quill-work neck sheaths he made for a couple of Glen Mock’s custom knives.

Shawn has been doing commercial quill-work since 1980, and, if you do anything for that long, it can get old. But Shawn avoided burnout by becoming a muzzleloading gun maker. Now, when he needs a break from quillworking, Shawn turns his hands to crafting a fine long rifle or trade gun. A couple of years ago, I managed to pick up a nice flintlock, 20-gauge, French Fusil de Chasse made by Shawn. It has become my go-to field gun and shoots either ball or shot with equal felicity, and it is an accurate, hard-hitting hunting gun.

As I write this, Shawn is building a .45-caliber, flintlock long rifle that I’ll use for competitive shooting at 18th century events and rendezvous. When it arrives, I’ll share it with you in an article.

Black Powder Gear

This winter, I was lucky to get my hands on a shooting bag built by Shawn. This bag is as functional as it is beautiful. It is a generous 10 inches wide by 12 inches tall. Lined with aged pillow ticking fabric, the main chamber is very roomy. Sewn to the back of the main pouch is a small pocket, for carrying small items like spare flints.

Shawn dyed the bark-tanned mule deer hide bag a medium brown. Called a beavertail, the flap of the bag ends in an oval shape. Shawn used the tanned skin of a beavertail to make the flap, making this an appropriate term. The beavertail leather has a very attractive and unique texture.

Adorning the main panel of the bag’s flap is a square piece of brain-tanned mule deer hide that has been stained a deep chocolate brown. On this panel Shawn embroidered a floral quillwork design. This is an original design of Shawn’s that combines Metis quillwork techniques with Pennsylvania Dutch folk art design influences. This is a beautiful piece of work. It required a powerful magnifying glass for me to see all of the fine detail.

Without a doubt, this is the most beautiful hunting bag I’ve ever held in my hands, and I wish I could say that it would be mine forever. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. The next stop for this bag is Lord Nelson’s Gallery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Lord Nelson’s Gallery is the country’s largest exhibitor of art related to the French and Indian War period done by the best contemporary artists in the country. Along with art, Lord Nelson’s also has an impressive collection of fine period accouterments. So, if you’re in Gettysburg this summer, you might get the chance to own the bag I covet. If you do get it, please don’t call me to rub it in. I already feel bad enough about giving it up. For more on Shawn’s work, visit websterquillandgunworks.com.

Editor’s note: This is not the first time Shawn Webster has appeared in American Frontiersman magazine. In fact, Shawn was the cover “mountain man” model (issue #191) for artist David Wright. Be on the lookout for more great pieces of art—from both men—in future issues. To purchase back issues of AF magazine, e-mail backissues@harris-pub.com or call 212-462-9525.

This article was originally published in the AMERICAN FRONTIERSMAN 2015 issue #174. Subscription is available in print and digital editions at OutdoorGroupStore.com. Or call 1-800-284-5668, or email subscriptions@athlonmediagroup.com.

This content was originally posted July 12, 2021, on Ballisticmag.com.

Read Next: Man In The Wilderness – The Other Hugh Glass Movie

Comments