If I’m in Maine, it’s raining. This trip was no different, with an early spring drizzle dancing on the lake’s surface as we put in on the southern corner like we had so many times before. As the sun began its westward procession across the gray sky, we began our northerly voyage over the crystal clear waters of Pond in the River, a geological and hydrological oddity on Maine’s Rapid River.

Like a Tolkien novel, the journey is part of the destination. We zigzag along the shore, probing likely structure with Golden Witches and Queens of the Waters cast on sink-tip lines. The ice has been gone for a couple of weeks now, but the possibility of pulling outsized trout from the still water remains. Several smallmouths intercept streamers meant for brookies before we pull the canoe ashore well ahead of the dam left over from the heyday of logging.

Pond in the River, a 469-acre blowout in one of Maine’s largest rivers, is one of the world’s preeminent brookie fisheries, but with warming waters and an incursion of smallmouths that prey on brook trout eggs and fry, it may not be that way forever.

Despite their common name, brook trout, Salvelinus fontinalis are actually a char. As such, they require clean, clear, cold water — the kind that is in serious decline these days on our warming, dirty planet. The 40-foot depths of Pond in the River afford thermal refuge for the fish in the extremes of summer and winter, providing the ideal habitat for Maine’s state fish to grow to sizes typically only seen in inaccessible spots — the kind of fisheries that require a floatplane to get to.

You don’t need a floatplane to reach Pond in the River, but it certainly helps. On one of my first trips there, I had the privilege of watching an old De Havilland Beaver scrape the treetops and skid to a stop across the water’s surface. If you don’t have a puddle jumper, getting there involves more than a few miles on gravel roads, most of which are remnants from the logging industry. There are a few access points that let you bushwhack your way down to the Rapid, but it’s easier to paddle across the pond — once you get the quarter-mile portage out of the way. However you get there, it’s not an easy trip, which is part of the reason why the fishing remains good.

Maine’s Rangeley region looks much the same now as it did when Fly Rod Crosby was paving the way for the Eva Shockeys of the world a hundred years ago, though there are a few more roads now. Many of the waters still fish much the same way they did when Carrie Stevens was designing the iconic Grey Ghost and all of the other classic fly patterns that are now staples. If one were interested in a brook trout of trophy proportions, Pond in the River and the Rapid itself are one of your best bets, floatplane or not.

One key difference in the fishery from the Carrie Stevens era is the illegal introduction of smallmouth bass to the Rapid River. During the 1980s, some fools dumped smallmouth bass into Umbagog Lake, the terminus of the Rapid, where they became well established. Since then, they have migrated up the Rapid and into Pond in the River. By the late 1990s, anglers were catching bass in runs that should only hold trout. Eventually, bass were found along the entire length of the Rapid. Alarm bells were starting to ring for one of the East’s greatest brook trout rivers.

When I first started fishing the Rapid, the banks wore signs warning of the invasive bass. The verbiage read that they must not be returned to the water if caught, which inspired many a shore lunch for others and me. If the bass were too small for the frying pan, they were tossed into the upland to fertilize the trees. But the bass wouldn’t be eaten into oblivion and thrived despite anglers’ best efforts. Statistics compiled by the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife indicate that the catch rate tripled from 2003 to 2013.

Though dams are not often thought of in a positive manner when it comes to cold-water fisheries, the one at the upper limits of the Rapid may prove to be the exception. Middle Dam, located on the outlet of the Richardson Lakes, has prevented smallmouths from entering other waters farther up the Rangeley chain of lakes. The dam has also proved vital in managing the invasive smallmouths in other ways, manipulating flows to limit smallmouth nesting success.

Brook trout begin spawning once water temperatures drop to about 45 degrees Fahrenheit. Once fertilized, the eggs have about a 100-day incubation period. This gives brook trout fry a couple of weeks’ head start on the young-of-the-year smallmouths. Briefly increasing the flow on the Rapid to about 1,200 cubic feet per second at the end of June blows smallmouth eggs off the nest and sweeps freshly hatched smallies downstream, while the slightly more developed brook trout can withstand the increased flow. Annual pulsing flows from Middle Dam during the late June to early July period have been implemented since 2010.

Is the strategy working? Definitely maybe. In the years since I first started visiting this unique water, I’ve noticed the size of the smallmouths increase. On my first visit over a decade ago, the small jaws seemed to be more numerous but significantly smaller in size. This could mean that bass nesting success has dropped off, with less competition for available food sources leaving the remaining population better fed. I have also seemed to catch more Atlantic salmon and brookies in recent years, though that could also be a product of more experience with the river.

Data compiled by the state seems to indicate success as well. Studies conducted in 2006 and 2007 showed that the approximately 12-hour releases during the peak of the bass spawn eliminated fry and eggs from about 50 percent of nests the researchers were observing. The last catch-rate survey, conducted in 2016, showed anglers caught 0.069 fish/hour fewer smallmouths — the first time since 1999 that the rate went down. While that is a seemingly minor dip, it could mean that the smallmouth bass production has finally decreased. At the same time, the catch rate for brook trout had increased by 0.20 fish/hour, evidence that the population was rebounding. Hopefully the trend continues, and the self-sustaining population of brook trout that call the 3.2 miles of the Rapid River home will return to historical glory.

Some years the river is more gracious than others. On my first visit, the spillway nearly bested me, requiring a cold swim after shedding my waders in the swift current. The memory of hypothermia was fresh in my mind as I took measured steps toward the prime run. This year it would reward us with brookies and salmon on Parachute Adams flies tossed between the raindrops, as we savored these moments that would someday be a midwinter’s night dream and the impetus for another late-night text. If you ever find yourself around North Oxford, Maine, grab a canoe and 5-weight and sample the population for yourself. Just remember to crush your barbs.

How to Fish Pond in the River

For more information on how the Rapid is currently being managed, see the Rapid River Fishery Management plan issued by the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. Fish nerds might also enjoy “Summer Movements of Sub-Adult Brook Trout, Landlocked Atlantic Salmon, and Smallmouth Bass in the Rapid River, Maine.”

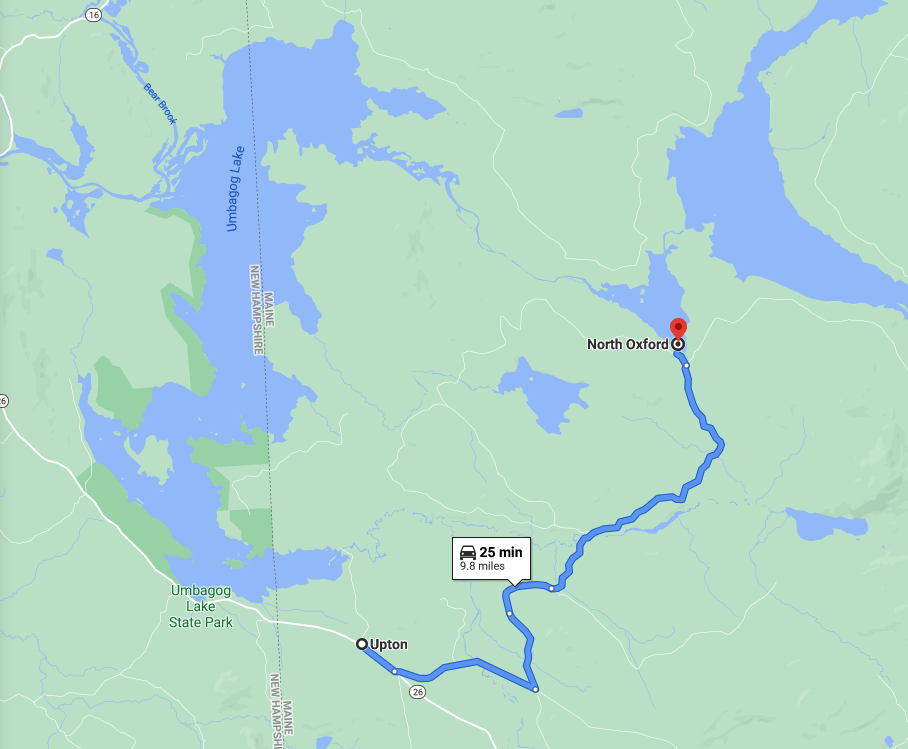

Though GPS systems have largely replaced paper for navigation, you’ll want to pack an Atlas & Gazetteer when you hit the back roads. The nearest town is Upton — though it’s not much of a town. The nearest gas station and tackle shop is LL Cotes in Errol, New Hampshire, on the southern terminus of Lake Umbagog, but in the grand New England tradition “you can’t get there from here.”

The launch is about 5 miles as the crow flies, but the circuitous nature of the logging roads makes the journey feel much longer. From Upton, turn left off of Route 26 onto East B Hill Road and follow a series of gravel roads to the public launch on the southeast corner of Pond in the River. It’s about a quarter-mile from the road to the put-in, so bring a friend or a canoe cart.

Tackle selection is simple, with a 9-foot 5-weight rod able to handle pretty much every situation you’ll encounter on the Pond or in the Rapid. If you plan on chucking outsized streamers like Sex Dungeons and Drunk and Disorderlies for the biggest fish, step it up to a 6-weight. Bring a floating line for surface work as well as a sink tip to probe the depths.

Streamers are the standard, so load up on Carrie Stevens’ patterns as well as more contemporary favorites — and don’t forget the humble Woolly Bugger. Nymphs produce all year, so stock up on caddis imitations and some attractor patterns. Hatches are rare, but they happen often enough that you should bring along a selection of dries. It’s caddis, caddis, caddis, but make sure you pack a few mayfly patterns in case you luck into a big hex hatch.

Comments