Nineteenth-century strongman Arthur Saxon was famous for backlifting 4,337 pounds. If that isn’t strength, then I’m not sure what is. What makes strongman squats like that so hard to consider today is the leverage required to move that much weight and the lack of dedicated equipment making it reasonable — or safe.

The strongmen of yesteryear developed this lift and others like it out of necessity, before the advent of a squat rack. Today, the imbalanced and often unilateral or one-sided nature of these movements are perfect for outdoor enthusiasts and hobby athletes looking to develop functional strength. These awkward lifts help train for the imbalance that daily activities apply to our bodies. These old-school exercises will help boost total body coordination and core stability, too.

Anderson Squat

Benefits: Control at depth, strength through full range of motion, power out of the bottom, impossible to cheat.

This variation is very uncommon in the gyms of today, but those who include this old-time lift reap huge rewards when they return to traditional squats. Named after legendary strongman and weightlifter Paul Anderson, this squat begins and ends at the bottom of the squat motion. This eliminates any advantage gained by the “bounce” or stretch-reflex that helps spring you out of the bottom position. You can perform the Anderson squat with the bar at your back or front, which adds another dynamic to this awesome lift.

For those looking to generate some serious strength and power, there is no better movement than the Anderson squat. Think of this as the dead lift of squats in that it is the most impressive expression of sheer strength available during a squat.

Cues: Set your safety racks at shoulder height at the bottom of your squat range of motion. Once you have your bar loaded up, approach it exactly as you would a back squat or a front squat with the exception that you are now at the bottom position. With a deep breath, brace your core and drive up on the bar until you reach a standing position, where you will lower down and repeat. It is important to pause at the bottom of each rep with the bar placed in the rack to truly eliminate the stretch-reflex. Failure to do so renders the move effectively pointless.

You will be surprised how much less weight you will be able to lift at first. The Anderson squat is one of the most humbling movements in the weight room and really highlights how we depend on the “bounce” with our standard squats. If you stick with this move for long enough, you will see a huge payday when you return to traditional back or front squats.

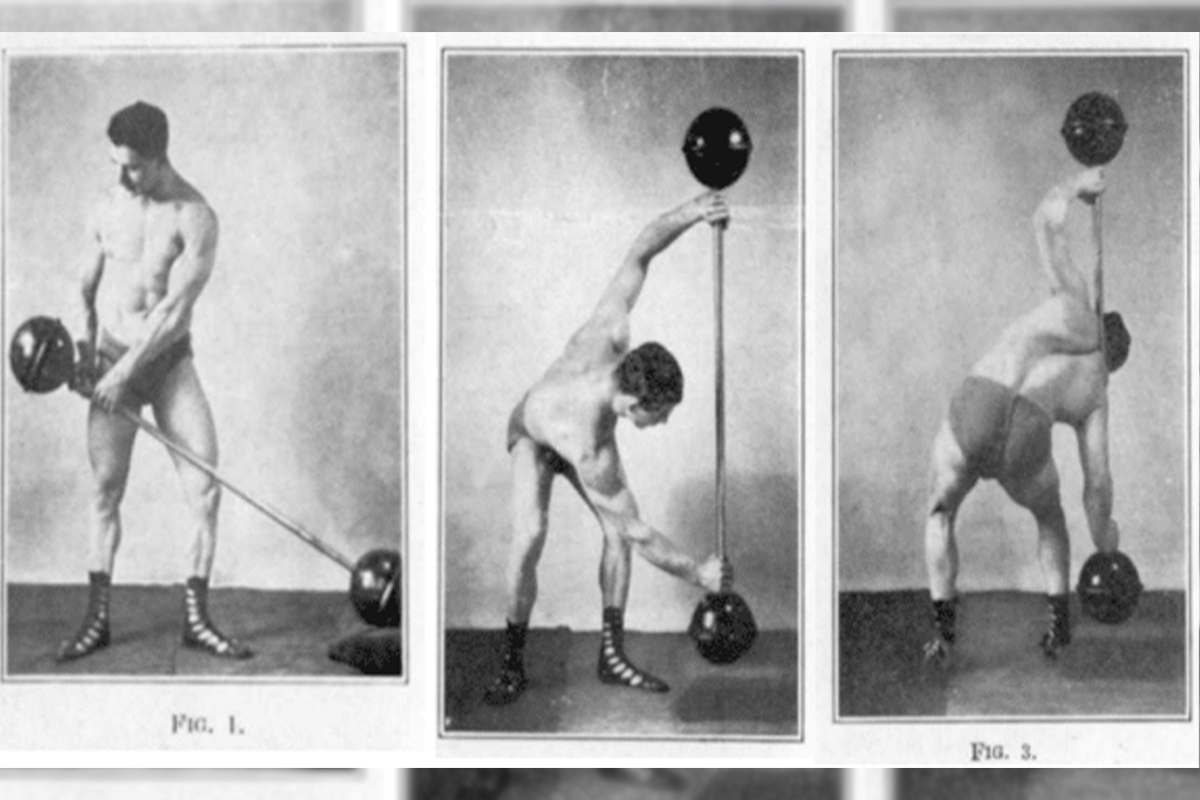

Jefferson Squat

Benefits: Quad strength, glute strength and activation, elimination of spinal compression, core stability.

Another old-timey strength movement comes to us from Charles Jefferson, a strongman who traveled with the Barnum & Bailey Circus. He was renowned for his chain-breaking abilities and unmatched feats of strength in the late 19th century. One of the major benefits of the Jefferson squat is its slight bias toward one leg. While both legs remain firmly planted on the floor, the positioning places a greater percentage of the weight on one leg. This may seem insignificant, but under high loads that weight shift can lead to some major benefits.

You will sometimes hear “Jefferson squat” and “Jefferson dead lift” used interchangeably, and while they share 90% of their mechanics, they are different in one major way. When performing the Jefferson squat, the lifter should place their hips low and begin the lift with an upright torso. This requires good mobility and a great degree of knee flexion. By contrast, the Jefferson dead lift can be performed with a more hinging motion, which will recruit more of the posterior chain.

Cues: After loading the bar on the floor, step up to and over the bar with one leg (the lead leg). In this straddle position, reach down and grasp the bar in your preferred grip (overhand, underhand, mixed). Drop your hips and raise your chest and begin driving off the floor. The bar will rise between your legs, stopping somewhere at the top third of your thigh. Dropping your hips down and back, return the weight to the floor and repeat.

It is important to note the rotational component of this lift. Because you have one leg in front, the bar will want to twist away from that leg. This added challenge is one of the major benefits of the Jefferson squat. Due to the biased nature of the lift, be sure to perform the same number of lifts with each leg forward of the bar so that leg development remains even.

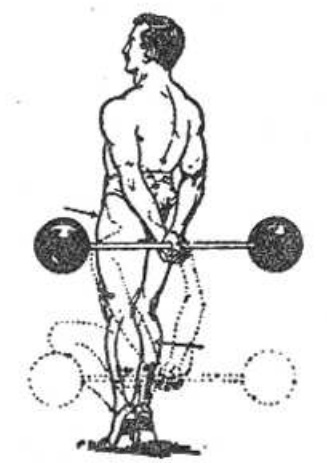

Hack Squat

Benefits: Quad strength, eliminates spinal compression, core stability.

Many will argue that the Hack squat is a dead lift. This argument has some merit, as the load does come from the ground with each rep like a dead lift. Regardless of how you want to classify this unique lift, it is an indispensable addition to your strength training repertoire. Named for George Hackenschmidt, the famous wrestler and strongman of the early 20th century, it first appeared in his book, The Way to Live, in 1908. Unlike any other squat, this variation begins with the weight placed behind your heels, and it is lifted much like a dead lift. The unique positioning of the barbell places the emphasis on the quadriceps, which is likely why it is considered a squat. You might be familiar with a hack squat machine from your local gym. These were invented to mimic the loading pattern of the traditional Hack squat but, as with most machines, isolate movements too far and eliminate some of the particular benefits of performing the move in the first place.

The Hack squat requires a great deal of strength and mobility to be performed correctly. As such, it is best programmed for intermediate and above lifters who should still approach the movement with relatively light loads to start.

Cues: Begin with the barbell on the floor directly behind your heels with your feet flat and placed beneath your hips. Reach behind you using an overhand, underhand, or mixed grip and grasp the barbell. Raise your shoulders so that your back is flat, sit your hips back as in the bottom of your squat, and begin driving off the floor. It is important to note that you will have to navigate the bar around your hamstrings to some degree; this is especially true if you have well-developed hamstrings. Once you reach a standing position, push your hips back, tracing the same path, and place the bar back in its starting position.

Zercher Squat

Benefits: Core stability, reduced spinal compression, improved upper back stability, carryover to your dead lift.

You are unlikely to see this squat variation in the average gym. Named after its creator, Ed Zercher, a strongman of the 1930s, the Zercher squat requires no squat rack and begins and ends each repetition with the barbell on the floor. Despite its lack of popularity, the Zercher squat is extremely effective at developing a strong upper back and core. Most lifters who perform it regularly find that the carryover is greatest to the dead lift, but that certainly doesn’t mean it should be set aside. The load it places on your quads is immense, and there is no middle ground when it comes to form. In order to execute the movement correctly, you must have a vertical chest, your knees must come apart, and your butt must travel down and back. Omitting any one of these important details will cause the weight to pull you forward or push you back. Positioning is key here.

Cues: The true form of the Zercher squat as we know it starts by deadlifting the bar from the floor, dropping into a squat position, and placing it on your upper thighs, hooking your elbows under the bar and pressing the weight up. For more novice lifters, the bar can begin in a safety rack just below sternum height. In the traditional form, this is a bottom-to-bottom squat, meaning there is no momentum to be gained by bouncing out of the bottom of the movement, and each subsequent rep begins anew with the dead lift and the squat — making for one killer movement. From the rack, this will look like a back squat with the exception that the barbell is in the crooks of your elbows.

Why include these crazy movements into your program? This series of movements will have you moving weights in new and exciting ways, but they take practice in order to perfect the techniques and truly reap their benefits. Their distinctive loading patterns require the activation of new groupings of stabilizer muscles and task your existing musculature in new ways, developing huge strength and increased stabilization. Finally, due to the unique positioning of these movements, you will increase your kinesthetic (or body) awareness, allowing for increased strength and athletic development.

Comments