The future of mountain lion hunting and trapping is under debate in Texas after an animal-rights group petitioned to change regulations within the state. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission (TPW) directed staff to form a mountain lion working group of landowners, land managers, academics, subject matter specialists, and other stakeholders to gather data on Texas mountains and offer feedback on potential management efforts.

A petition from Texans for Mountain Lions to the TPW in June sparked a decades-old debate over the need for — and extent of — a mountain lion management plan in the state.

Specifically, the petition asked for:

- a statewide abundance study;

- mandatory reporting of harvest;

- renewed trapping regulations;

- a ban on “canned” mountain lion hunts, which is already illegal under Texas law;

- the formation of a lion management advisory group;

- and a bag limit of five lions in South Texas.

TPW denied the petition, but not before battle lines were drawn. The fight went hot on Wednesday during the TPW’s annual public meeting, before the commission’s Thursday decision to appoint a working group.

At the public hearing, two distinct narratives became apparent. The first: pro-animal protection, which relied on emotion and a few muddied facts. The other: anecdotal, boots-in-the-field experiences with mountain lions.

Pro-petition property owner Gary Barton talked about a live coyote he found caught in a leg trap on a neighboring ranch. He could only imagine the pain a mountain lion would suffer in the same situation.

“Currently, there are no requirements to check traps in Texas,” he said. “Trap owners should be required to monitor active traps daily at the very least. If a hunting dog, a hiker, or a child accidentally stepped on an active trap, they could easily suffer a long horrible death from exposure like mountain lions.”

(In Texas, trappers are required to check traps every 36 hours.)

Ben Jones, executive director of the Texas Conservation Alliance, referenced a film directed by Ben Masters — a fourth-generation Texan and one of the principal Texans for Mountain Lions coalition members — as a wake-up call to the plight of the mountain lion.

“I’m really grateful to the makers of Deep in the Heart for highlighting and illustrating the reality of mountain lions in our state so vividly,” he said. “Shameful canned hunts, exposure, heat exhaustion, dying of thirst. You know, 40 years ago, my dad taught me and my brother to hunt and trap in the deep of Piney Woods. There’s one lesson among many that went down deep. And even as a distracted kid, I’ll never forget that. ‘Boys, we never let an animal suffer needlessly.’”

Canned hunts — when trapped animals are released within a high-fence enclosure to be hunted by a paying client — are already illegal according to TPW regulations.

“I believe Texans want mountain lions on the landscape. I know that I do. But [Texans for Mountain Lions’] attempt to strong-arm Texas Parks and Wildlife with a petition that calls for strict management, and quotas without sufficient scientific data to support it simply can’t be tolerated.”

Cable Smith, host of the Lone Star Outdoor Show podcast

Masters, the filmmaker, used his time to point out that he guided hunts in South and West Texas to put himself through college. But he also painted a bleak future for mountain lions and potentially his children.

“By the time my kids are my age, the human population will have increased from 30 million to 50 million people,” he said. “In South Texas, where lions are most likely at risk, the landscapes are becoming increasingly fragmented. It’s also possible that when my kids are my age, there will be a border fence that stretches along South Texas that would prohibit migration of mountain lions into Texas.”

“There are many others that are very concerned about the South Texas mountain lion population,” Masters continued. “So, on behalf of my children, I encourage you to consider the proposals we put in place and to create a management plan that ensures that healthy mountain lion populations always roam both South and West Texas.”

On the other side of the issue, Jeremy Harrison, whose family has been ranching in the Trans-Pecos region for almost a century, took issue with the science referenced in the petition.

“Perception is everything,” Harrison said. “To collect real unbiased data, collect real mountain lion population numbers, you will need the support of private landowners, which comprise 93% of the state of Texas. For landowners who willfully participate, the perception cannot be that the game is rigged or predetermined.”

Harrison’s father, Damon, put a finer point on it.

“I understand that we’ve got a so-called stakeholder group that put forth some proposed regulation,” said the elder Harrison. “Stakeholder to me as a person that gets up in the morning looks out the window and says, ‘Oh golly, I like mountain lions.’ I am the last thing you would ever call a stakeholder. I’m what you call a shareholder. I’ve got money on the line. My family has been ranching in the Trans-Pecos area in Terrell County for 94 years. I’ve got over $12 million invested in livestock and feeding mountain lions. The slap in the face, I think, with this proposal is that the stakeholder group doesn’t propose that they do anything. It’s all back on the landowner. I’m asking you all to take a serious look before you make any changes to that. Just because a stakeholder group wants to change the status quo doesn’t mean it’ll end up well for any of us, including the mountain lion.”

For Cable Smith, a native Texan, a lifelong hunter and angler, and host of the Lone Star Outdoor Show podcast, the coalition’s tactics didn’t sit well with hunters, ranchers, and rural Texans.

“I believe Texans want mountain lions on the landscape,” Smith said. “I know that I do. But [Texans for Mountain Lions’] attempt to strong-arm Texas Parks and Wildlife with a petition that calls for strict management, and quotas without sufficient scientific data to support it simply can’t be tolerated.”

State lawmakers codified mountain lion hunting and trapping in 1973 when the state legislature passed the Non-Game Species Act, designating mountain lions as a non-game species.

Before the act passed, in what was likely a preemptive move, the Sierra Club had introduced two bills to the legislature seeking to have mountain lions designated as non-game, and both bills failed.

Under the non-game designation, there are no closed seasons, bag limits, or possession limits on mountain lions, and Texans are free to shoot or trap them at any time by any lawful means or methods on private property. Bag limits and seasons only apply to public land.

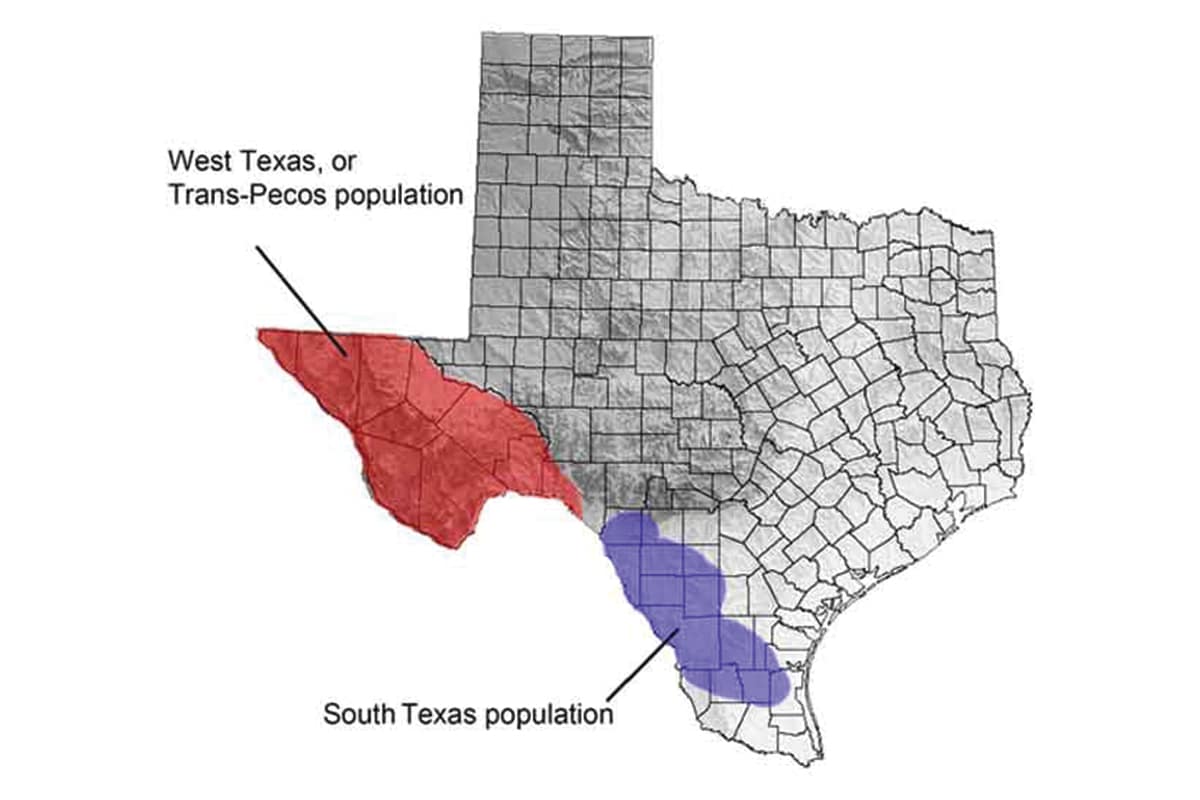

Currently, mountain lions roam in the Trans-Pecos region (or West Texas) and South Texas. The West Texas population appears strong, likely from a shared border with Mexico and New Mexico, while population numbers in the south are lower; the animals are not considered endangered in either area.

Even with the opposing perspectives during the public hearing, there was a consistent call for more data about the mountain lions themselves and the formation of an advisory group that would help direct a path forward for management decisions — so the commission’s actions are a positive step forward.

Ryan Trimble, a reporter for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, voiced support for forming such a group.

“A lot of states know how to manage these things,” he said. “But we’re Texans; let’s do it the Texas way. There are a lot of smart, capable, knowledgeable people here. I think they’re reasonable. I think there’s an opportunity here to work together and find solutions and give all stakeholders an opportunity.”

Robbie Kröger is the host of the Blood Origins podcast, which explores the deep history of our hunting heritage. He told Free Range American that he had Masters as a guest on his pod specifically to talk about the Texas mountain lion management debate.

“The advisory group is probably the best next step,” he said. “Everyone’s going to have a seat at the table, and everyone will have a say. Hopefully, cooler heads prevail, and everyone makes an amicable decision on what’s next.”

With some accurate data on mountain lions in Texas, that just might be possible.

READ NEXT – Read More Stories About Big Game From Across the Country in Our Whitetail Archives

Comments