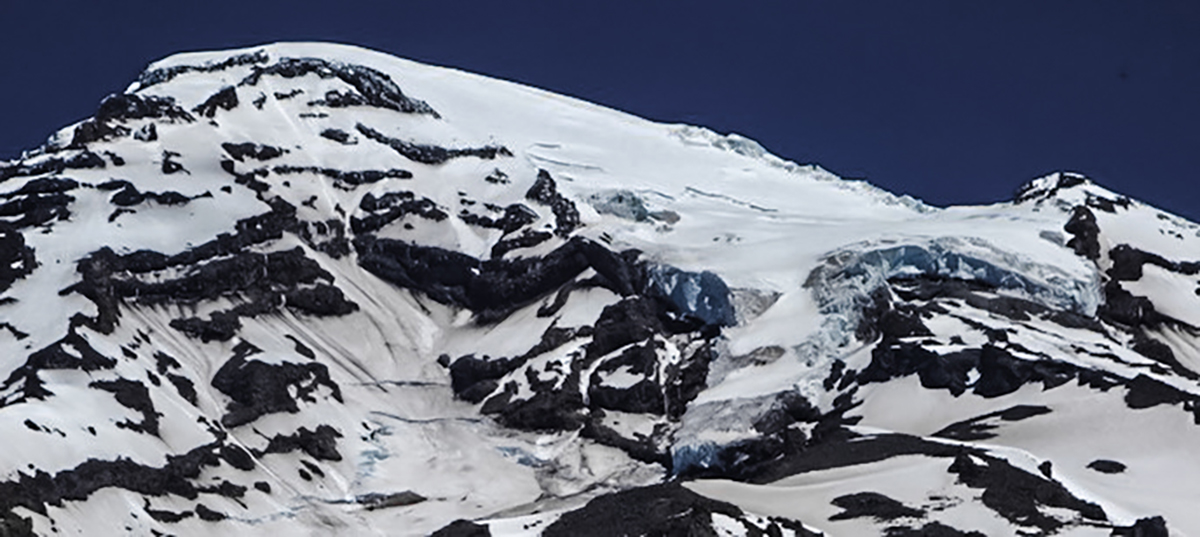

He was trapped in an ice crevasse knifed into the side of Mount Rainier, his arm and leg busted, his buddy nearly eight stories above him getting whipped by winds blasting the snowy ridge at 50 knots.

But he had excellent cell phone service. And so, at roughly 10:30 a.m. on May 12, he rang Mount Rainier National Park dispatch and asked for help.

National Park Service officials knew their own rescue choppers were grounded. But someone had to reach the two mountain climbers stuck above 12,000 feet on a Washington ridgeline swept by gusts racing faster than pronghorn antelopes.

So they called in the US Army.

“He was down there trapped between two chunks of ice at the bottom of the glacier,” said Chief Warrant Officer 4 Collin Johnson, a former Ranger who now flies CH-47F Chinook heavy cargo helicopters for the “Hookers” of Company F, 2-135th General Support Aviation Battalion, out of Fort Lewis.

It was the unnamed man’s third call to the park authorities. He first phoned 911 at 8:10 p.m. on May 11 to warn dispatchers that worsening weather had stopped their ascent to Rainier’s summit on the Kautz Glacial climbing route. He said they were roughly at 12,800 feet, just below the Wapowety Cleaver, but didn’t need help.

Yet.

“You could go from bright and sunny and beautiful to 30 minutes later you can’t see a foot in front of your face,” Johnson told Coffee or Die Magazine, adding that even the most experienced climber can die on a mountain that “makes its own weather.”

The next morning, at 7:30, the hiker called again to alert officials they were starting down the stratovolcano on the Disappointment Cleaver route. Three hours later, he punched through the snow and fell into the crevasse.

And the mercury had plummeted to 15 degrees. His buddy dropped him a camp stove to keep him warm on the ice.

RELATED – 2 Rescues in 2 Days: AZ Clusterf*CK Serves as Hiking Safety Reminder

Normally, the climbers would’ve had to wait for more than two hours for military rescuers to reach them, but they got lucky. Pararescuemen from the US Air Force’s 304th Rescue Squadron out of Portland, Oregon, were nearby on a training mission with Johnson’s US Army reservists, and they hadn’t left yet.

Unfortunately, the weather “just wasn’t playing that day,” and they had to abort a flight until the next morning, Johnson said.

A Chinook with the PJs on board took off around 6:30 a.m. on May 13. Johnson wasn’t in the cockpit this time. He was tasked with being the liaison between the injured climber and the rescue team.

So he had to break the bad news: the turbulence and downdrafts were so severe that the helicopter crew couldn’t insert the pararescuers. But at least they had a glimmer of good news. The injured man’s pal was still alive, which meant something.

Over the past 15 years of running rescue missions on Rainier, Johnson has gone up to retrieve 16 climbers. And only three lived long enough for the soldiers to bring them back.

The Chinook crew and the pararescuers returned to their station to refuel and wait. Several hours later, the winds dipped to 35 knots. They flew to the glacier again, aiming to reach the uninjured climber, who was most likely to die in the snow.

They hoisted him off the glacier and also dropped a survival package for his injured buddy, including a cell phone charger, food, and dry clothing to “hopefully sustain him” until rescuers could make another trip, Johnson said.

The crew rushed the rescued climber to Madigan Army Medical Center.

Now it was time for the National Park Service’s elite rescue team to have a crack at the injured man in the crevasse.

Mount Rainier’s aviation manager, Glenn Kessler, told Coffee or Die the park reached out to Hillsboro Aviation, which scrambled an Airbus H125 helicopter.

Rescuers have long dubbed the bird an “A Star B3,” based on its former name when it was manufactured by Eurocopter. The workhorse chopper holds the world record for the highest-altitude landing and takeoff, a feat performed at 29,029 feet atop Mount Everest in 2005.

The Hillsboro Aviation pilot inserted four climbing rangers at 13,000 feet on the slope of Rainier, a few hundred feet above where the injured hiker fell into the crevasse. They started down the glacier.

But Johnson told Coffee or Die the rangers had faced a tricky technical problem of how to get one of their own climbers down into the crevasse and safely extract the injured man.

According to the National Park Service, the rescue team extracted the man from the crevasse, prepped him for transport, and then coordinated a short-haul rescue, lifting him off the glacier and into the H125.

The helicopter touched down in the valley of Kautz Creek, where the Army’s Chinook had staged after returning from Fort Lewis.

The rangers handed the patient off to the PJs, and the CH-47F flew off again to Madigan. Despite having spent 18 hours deep in a crevasse, the “pretty dang tough” climber appeared to be alert and seemed “ready to get out of there,” Johnson said.

Everyone is still marveling at the excellent cell phone reception he kept throughout the long rescue.

“I don’t know what phone service he has, but that’s a good one to have if you can be 80-foot down, still talking on your cell phone,” Johnson said.

READ NEXT – ‘Jesus, There It Is’ — Inside a Daring High Country Rescue

Comments