On Nov. 1, 1914, Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim set the record straight in an article for The New York Times titled “‘How I Invented Maxim Gun’ — Hiram Maxim. Outbreak of World-War Moves Veteran American Inventor to Describe for The Times His Epoch-Making Idea.”

Maxim, 74 at the time the article was published, died just two short years later. Although he had acquired a fortune for his killing machine, he believed his invention — which went on to change the history of warfare — was a mistake. His legacy, carried on by his son Hiram Percy Maxim, sealed the Maxim family’s fate as one of the most significant father-son duos to ever enter the firearms industry.

The father invented the modern machine gun. The son silenced it.

The elder Maxim was a prolific inventor born in rural Maine in 1840 and raised around the New England area. The mechanic, the eldest son of a farmer, received numerous patents for his inventive ideas. The first was for a hair-curling iron. Then came an automatic sprinkler that alerted the local fire department by telegram once it was triggered by fire. The chronic tinkerer designed an improved mousetrap and even experimented on a flying machine a decade before the Wright brothers took flight.

It was his demonstration of an electric pressure regulator at the first International Exhibition of Electricity held in Paris, France, in 1881 that first gave Maxim some fame. The French government made him a chevalier de la Légion d’honneur for his work. The following winter, he met a “clever American” in Vienna, whom Maxim credited with inspiring him to build the world’s first portable, fully automatic machine gun. The American had commented that Maxim’s electric machines weren’t going to make him rich, while a new weapon would bring not only fame but fortune.

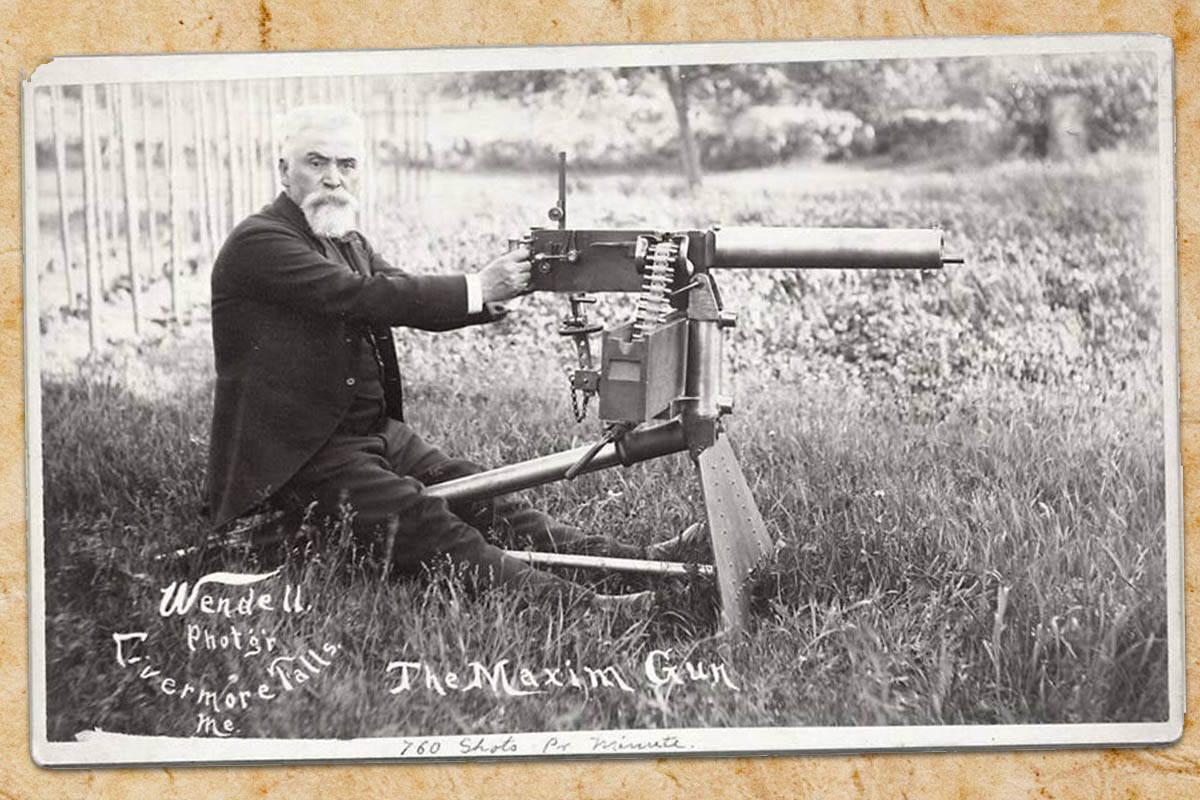

“Later on I came to London, established a little workshop, and made a gun that actually loaded and fired itself by energy derived from the recoil,” Maxim wrote in The New York Times. “It was a veritable nine days’ wonder: every one of note, from H.R.H. the Prince of Wales down, came to see me and fire my gun.”

It was unlike anything anyone had ever seen before. Its precursor, the Gatling gun, was a hand-driven and crank-operated gun that had six or 10 barrels, while the Maxim Gun had only a single barrel.

“When I was asked to fire it before the Government officials at Enfield I fired 333 rounds in half a minute and a belt of 2,000 cartridges in slightly over three minutes,” he wrote in The New York Times. “Then the British government gave me a large order which enabled me to organize a company and fit up large workshops.”

Business was booming, and within just six years of founding the Maxim Gun Co. in 1884, Maxim had license agreements with the British, Austrian, German, Italian, Swiss, and Russian armies. After a dozen years in operation, his company was acquired by Vickers Ltd., who then used his proprietorship to manufacture Vickers machine guns, which became standard issue firearms for the British Army during World War I. These bullet-spitters killed millions of people, and as a result, World War I assumed the nickname “the machine-gun war.”

Maxim also developed his own smokeless gun powder called cordite to improve its efficiency. Remarkably, Maxim even wrote how his brother named Isaac changed his name to Hudson in an attempt to hitch on to his success.

“But later on certain events took place in which the ‘H. Maxim,’ which was supposed to be the Hiram Maxim, became Hudson Maxim, and that is the way that Hudson Maxim became ‘the inventor of the smokeless powder’ in the States,” he wrote in The New York Times in 1914.

While Maxim’s brother attempted to make it big using the family name, Maxim’s son, Hiram Percy Maxim, built an empire of his own. “I suspect I had one of the most unusual fathers anybody ever had,” he wrote in his book A Genius in the Family, according to the Hartford Courant.

The Brooklyn native went to school in the Boston area, graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1886 at age 17. Like his father, he had an eccentric mind and curiosity for innovation. He took a gasoline engine, jury-rigged it to a tricycle, and attempted to ride it from Hartford, Connecticut, to Springfield, Massachusetts. Although his first two attempts failed, he recalled the successful third attempt: “At that moment, I would not have swapped my position for any other on Earth.”

In the 1890s, he worked for the Columbia Automobile Co., where he designed one of the world’s first gasoline-powered production cars. These vehicles had loud exhaust systems, and the younger Maxim developed silencing devices to limit their sound. Soon, he realized these devices could be applied to other machines, and he used similar technology to produce the first commercially available firearms suppressor in 1902. Seven years later, he patented his proprietary tube that attached to the barrel of a firearm, just as it would’ve to a car muffler, to reduce noise and muzzle flash.

While the family behind the machine gun and the suppressor contributed substantially to society and warfare, the elder Maxim ultimately believed his greatest invention was a lifesaving apparatus known as the medical inhaler. The idea formed while he was suffering from a serious case of bronchitis in 1900. Although it treated his ailments and that of many others, his friends in the firearms industry destroyed his reputation, saying he was “prostituting his talents on quack nostrums.”

“From the foregoing it will be seen that it is very creditable to invent a killing machine, and nothing less than a disgrace to invent an apparatus to prevent human suffering,” Maxim wrote in his autobiography, My Life. “I suppose I shall have to stand the disgrace which is said to be sufficiently great to wipe out all the credit that I might have had for inventing killing machines.”

Read Next: This Is How Firearm Suppressors Work

Comments