If this content looks familiar, it’s because we posted this Matt Rinella op-ed two weeks ahead of time. Our intention was to drop it timed to the MeatEater podcast, embedded below, where Matt and Steve get into the value of social media in hunting. We jumped the gun, and then pulled it. Our bad. Well, now, you can read the full essay, unedited, as it originally appeared.

Matt Rinella is a grown-ass man with spicy-ass opinions. While we at FRA do not agree with all of his thoughts presented below, we’ll defend his right to air them till the end. We know one thing for certain: It’s gonna be an awkward fucking Christmas at the Rinella house. – The Editors

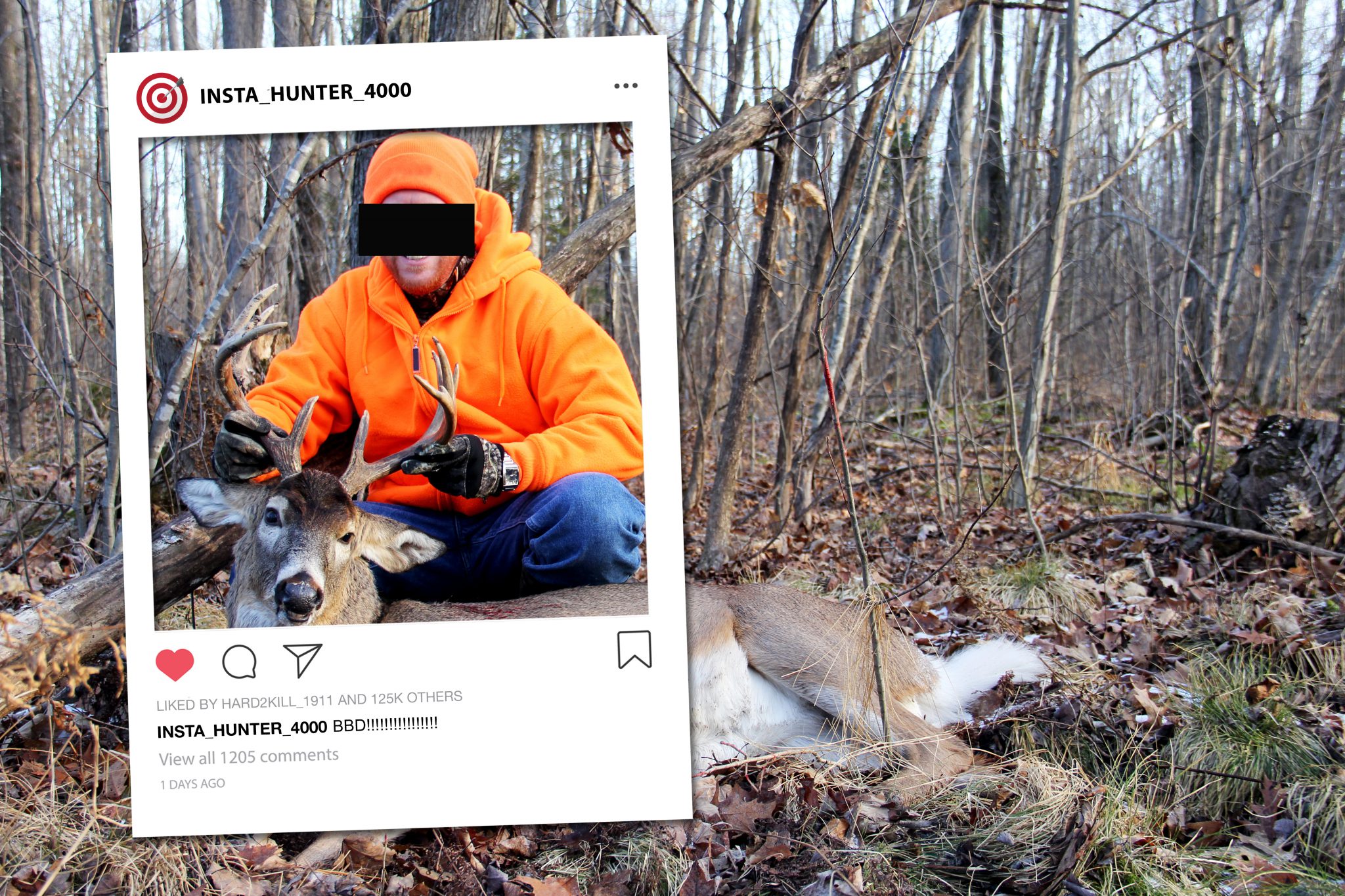

Over the past decade, hunters have increasingly publicized pictures and videos of their kills to large audiences on social media. This monumental change in hunting norms occurred gradually and with little thought for its consequences. These consequences are overwhelmingly negative. Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for sharing photos of harvested game with friends and family. I strongly support individuals and organizations that use social media to cover issues of importance to the hunting community. But it is time to unfollow hunters who post pictures of dead animals to hundreds, thousands, or even millions of, mostly, strangers.

Social media has corrupted our motivations for hunting and is risking the future of the very activity we love so much. Traditionally, we hunters took to the woods for hides, horns, meat, personal enjoyment, and a sense of self-reliance. Now, for the first time in human history, many seek a digital harvest. Rather than butchering meat for the freezer or tanning a hide, these kinds of hunters mostly want photos on their iPhones to beam out across the internet. More than cooking and eating what they shoot, they’re interested in exchanging it for likes and followers — and even corporate sponsorships in gear and dollars.

With my last name, this may strike some as a curious position. I’m the brother of Steve Rinella, the founder of MeatEater and maybe the most influential hunter in America today. While I dearly love Steve and am close with some of his coworkers, I’ve come to realize their approach — and the approach of many others — of blending hunting and media, and their efforts to publicize and commodify hunting and wildlife via every available digital platform, undermine hunters everywhere. It’s easy to forget these days that people can remain friends despite vehemently disagreeing, but we’ve managed to do just that.

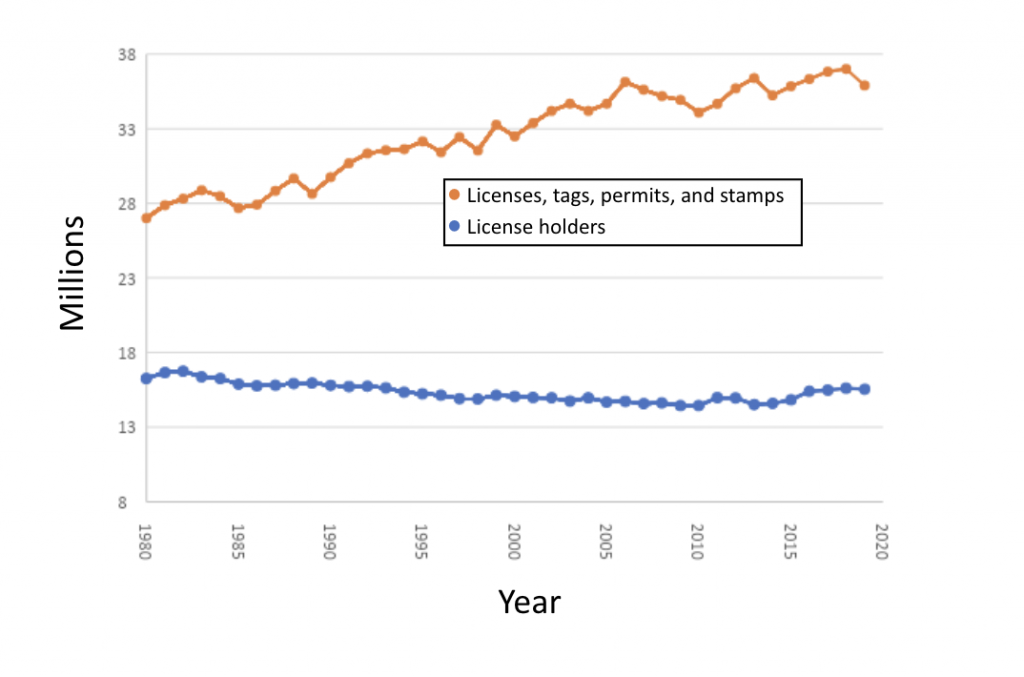

My argument starts with the fact that, in much of the US, public-land hunting is so overcrowded it’s no longer worth it. The mainstream and hunting media have run articles bemoaning declines in hunter participation for years, but this is utter nonsense. The number of hunters is extremely difficult to determine, and even if hunter numbers have dipped slightly since the 1980s when US Fish and Wildlife Service data indicate they peaked, it’s irrelevant. Existing hunters are hunting more. When I crunched the data, it became clear that hunting license sales increased a whopping 30% between the 1980s and 2010s, and then the COVID-19 hunting boom increased hunter and license numbers even more. So, even if there are a few less hunters, those hunters are buying more licenses and spending more time crowding the woods.

Also, since the 1980s, the American landscape has changed in major ways. The US population size has increased by a third, the square footage of housing per person has doubled, and many former hunting spots are consequently residential neighborhoods now. The US simply doesn’t have the habitat needed to support the wildlife and hunters it used to.

As a result, big game draw odds have plummeted, private lands are increasingly leased for hunting and thus off-limits to the public, and public land hunting often begins with struggling to find parking at the trailhead, followed by struggling to find animals so pressured they suffer from PTSD. According to 2017 survey data, over half of hunters have abandoned spots due to crowding. In short, hunter numbers have grown beyond what the resource can support. I believe social media is largely responsible for this because it draws people afield under false pretenses and encourages hunting for unjust reasons.

I’d be remiss if I ignored my own history with hunting social media. I was never big on posting grip-and-grins online. Years ago, I completely stopped after seriously asking myself why I wanted lots of people to see what I had shot. Upon reflection, I realized bragging was my sole motivation. This troubled me. I’ve always had a low tolerance for bragging by others, so I disliked realizing I was guilty of it myself. It didn’t help that I was bragging about dead animals harvested for food. This seemed more consequential and perverse than the soccer trophies, kitchen remodels, and other inane shit people brag about online.

The Negative Consequences of Hunting Social Media

For proof that social media, and hunting television, are increasing hunter numbers on already overcrowded public lands, consider what hunting influencers sell their followers on Facebook and Instagram and through their TV shows. In addition to hunting products, influencers like my brother sell books that teach rudimentary hunting, game cooking, and backcountry survival skills. Many are now teaching classes where students learn elementary woodsmanship, game calling, map reading, and strategies for applying for tags.

The target audience for all this is clearly hunting-curious nonhunters because seasoned hunters don’t need 101-level how-to content. If you have any doubt that motivating people to hunt and selling them products is big business, consider how many influencers do it. Here, for example, are more than 200 of them on Instagram. In addition to inspiring people to hunt, influencers inspire people to become fellow influencers. They do this partly by example and partly by teaching the relevant skills to do so, like how to attract sponsors and how to film their hunts. In other words, influencers motivate people to hunt for the same shitty ego- and profit-motivated reasons they hunt themselves.

Top hunting influencers like to call themselves conservationists, but the fact of the matter is influencers are terrible for habitat. No matter how great areas look in terms of feed and cover, game can’t live where there are hunters on every ridge. That’s exactly the situation influencers have created in their quest for more hunter-customers. Most influencers don’t have to hunt the places they’ve blown up because they largely hunt private land, take expensive trips to remote hunting destinations, and enter pricey limited tag lotteries throughout the US and beyond.

Influencers like to believe they’re elevating our reputation among the nonhunting public, but social media has severely damaged our reputation among nonhunters as well as reduced hunting opportunity. For example, read about the banning of grizzly bear hunting in British Columbia or watch The Women Who Kill Lions on Netflix. Or Google something like “social media hunting controversy” and settle in for a very long read.

Moreover, hunting influencers routinely engage in selfish, greedy behavior that poses threats to our reputation among nonhunters. Generating enough content to gain big followings and attract sponsors necessitates gobbling up tags and killing more than one needs. Top influencers commonly kill three or more elk a year along with a variety of other game. If you’re reading this, you’re probably following several of them right now.

If I was a nonhunter doing a quick scan of hunting social media, my gut response would be one of shock. It is a cornucopia of carcasses with zero explanation of what they plan to do with all that meat. If you’re a nonhunter reading this, please believe many traditional hunters are as disgusted by all this greed as you are. Traditional hunters believe wild game is a precious resource, and we harvest only what we need to eat between seasons, thereby increasing the chances for other hunters to take an animal.

Hunting social media is also horrible for public access. Friends growing up in the rural Montana community where I live remember freely hunting the surrounding ranchlands. A tractor repairman friend remembers having permission to hunt a 100-plus-mile swath running from eastern Montana all the way to South Dakota. Access started dwindling in the late 1980s with the advent of cable-TV hunting shows. These shows increased the appeal of hunting to the point where people became willing to pay big money to lease private hunting lands. Nowadays, it’s laughable to think banging on doors will result in hunting permissions in this prairie country because years of social media hype have made un-pressured ground so rare and monetarily valuable that landowners can’t resist charging for it. Hunting influencers like to pretend fellow hunters are their stakeholder group, but their real stakeholders are large landowners and the hunting industry.

Social media hunters further degrade opportunities for traditional hunters by deceiving people into thinking hunting is something it’s not. When famous hunting personalities pay to kill elk on ranches that are off-limits to the public, what they’re doing is more like slaughtering livestock than hunting wild elk. If that’s what gets them off, great, but putting videos of their “hunts” on social media without indicating they are stalking areas off-limits to the public dupes legions of newbies into thinking publicly accessible basins are brimming with bulls just waiting to be shot. Nothing says, “let them eat cake,” quite like using social media to inundate traditional public land hunters with throngs of aspiring hunting influencers while stalking quasi-domestic wildlife on private ranches.

I can’t understand being proud enough of this fantasy hunting to film it or brag about it on podcasts. Aren’t the videos a tacit admission one lacks the tenacity for real hunting? Many traditional hunters think so. I’d rather kill a one-eyed calf with a limp on public land than a half-tame giant that’s only accessible to people who can afford to pay for it. At a bare minimum, these “hunters” should explain to their followers that they’ve paid to stalk glorified cattle at hunting amusement parks. Then they could give a virtual tour of the lodge and a cost breakdown.

Here is perhaps the biggest problem with hunting social media: It is blatantly dishonest. It doesn’t take much hunting experience or familiarity with wound-loss data to see that social media hunters regularly hide the sorrowful side of killing animals for sport and meat. Social media shows too many smiling faces and too few fading blood trails. I know hunters that upload their grip-n-gloats before the meat cools when things go right but post nothing at all when they wound and lose game. Even major hunting publications encourage this lying by omission by discouraging hunters from posting videos of poorly hit game.

“Keep on hunting, but post nothing in 2022. This will prove you’ve moved past the attention-seeking toddler stage in your development as a hunter and now go afield for mature reasons.”

Showing only the happy parts attracts people to hunting on false premises, which is deeply unfair. It causes people to gear up and head afield thinking they’ll simply pull the trigger and drag their winter meat back to the truck. It’s not a true representation. The cold, hard fact is that pulling the trigger sometimes results in wounded animals and severe regret. This is especially true for new hunters. If influencers insist on recruiting new hunters and selling them gear, they should at least have the decency to ensure these hunters go into it with their eyes wide open. Of course, honest social media that consistently shows wound loss would provoke public outrage. As such, the influencers have painted themselves into a corner: Showing only the happy parts is lying and showing everything could destroy hunting. If they want to stop lying while maintaining our right to hunt, the only option is to take hunting offline.

What’s Lost if We Stop Posting Harvested Game?

As long as there have been cameras, hunters have been taking pictures with their game animals. Before the internet, these photos were displayed in albums and sometimes on walls in sporting goods stores. While the pictures aren’t new, the motivations for showing them, and the numbers and types of people that see them, have changed dramatically. Instead of a few family members or hunters in bait shops seeing the images, they are broadcast to everyone willing to look at them across the internet. This mass posting of dead game has become so common that it’s tempting to think something virtuous might be lost if we stop doing it.

To determine what’s at stake, I recently asked eight hunters who are widely followed on social media why they show us what they shoot. If they can’t explain why looking at what they kill is indispensable to the future of hunting, who can?

Their responses included “picture storage” and “informing friends what I’ve been doing.” Both are goals easily achieved without hundreds or thousands of followers. Most other motivations I heard about clearly don’t benefit the hunting community, such as “gaining credibility as a hunter” and “being addicted to the adoration” of followers, as two interviewees put it. One said, “It’s only worth [posting dead game] if people buy something,” and six of the eight admitted bragging was a motivation.

One motivation mentioned to me that demands more serious consideration is “celebrating the animal.” This could ostensibly benefit the hunting community as it could be seen as a positive to nonhunters watching. But do they mean celebrating the animal’s magnificence? If so, why not stick to photos of living animals? All animals look way better alive. Do they mean celebrating the animal’s life like we do loved ones at funerals? If so, why don’t we post pictures of open caskets to celebrate departed loved ones? When people say they show thousands of people what they shoot “to honor the animal,” much as I want to believe their motives are pure, all I hear is “to honor my abilities.” They’re honoring themselves, not the animal.

One interviewee said his motivation was to “portray hunting honestly” as a counter to all the dishonest depictions on social media and television. I’m positive this interviewee provides warts-and-all depictions of real hunting. I know the guy. He once released a heartbreaking video involving an elk he wounded. Nevertheless, it’s impossible to regularly consume hunting social media without regularly consuming bullshit, and there’s no way to distinguish the truth from the half-truths and outright lies.

Another motivation cited by the social media hunters I spoke with was promoting acceptance of hunting by illustrating field-to-table connectivity. To me, it’s a stretch to think nonhunters learn anything profound that revolutionizes their views on hunting when we post dead deer followed by a recipe for venison osso buco.

What Should We Do About It?

My brother Dan has joked about developing an internet-enabled rifle scope that automatically uploads kill shots to a hunter’s social media feed. His joke illustrates how hopelessly entangled social media is with hunting. Prospects for disentangling the two seem dim. Once before, however, hunters did abandon a common practice that wasn’t serving them. Through the 1980s, visibly transporting big game on vehicles was common. Then, in the 1990s and early 2000s, sportsmen’s groups, hunting magazines, and game management agencies began encouraging hunters to conceal carcasses to avoid offending nonhunters. The campaign seems to have worked some because I don’t see as many predominantly displayed deer on the highway as I used to.

If we unfollow hunting social media, we’ll do much more than avoid further public relations problems. We’ll be better, happier, and more successful hunters. In addition to no longer completely wasting time and suffering other downsides of staring at phones, we’ll stop contributing to a system that:

- Incentivizes hunting for the wrong reasons

- Diminishes draw odds

- Crowds public hunting grounds

- Makes wildlands uninhabitable for wildlife

- Pays landowners to lock out the public

- Degrades our reputation among nonhunters

The solution to all this is simple. I’m appealing to hunting influencers: Stop posting it. I’m appealing to hunting content consumers: Stop following it. I’m appealing to all hunters everywhere: Get on board with my New Year No Post Challenge. Keep on hunting, but post nothing in 2022. This will prove you’ve moved past the attention-seeking toddler stage in your development as a hunter and now go afield for mature reasons. More importantly than proving it to others, you’ll prove it to yourself. Is hunting still fun without the likes?

When it comes to hunting, we should take our lead from the Ju/’hoansi people of the Kalahari Desert, a hunter-gatherer tribe that the anthropologist Richard Borshay Lee studied in the 1960s and 1970s. Ju/’hoansi customs strongly encouraged humility, as quotes from a tribesman illustrate:

“Say that a man has been hunting. He must not come home and announce like a braggart, ‘I have killed a big one in the bush!’ He must first sit down in silence until I or someone else comes up to his fire and asks, ‘What did you see today?’ He replies quietly, ‘Ah, I’m no good for hunting. I saw nothing at all…maybe just a tiny one.’ Then I smile to myself because I know he has killed something big.”

The contrast between Ju/’hoansi hunters and social media hunters couldn’t be sharper. These humble tribesmen were reluctant to tell their closest friends and neighbors they had killed something. Conversely, social media hunters tell the whole world. The Ju/’hoansi had the right idea. The proper attitude for the hunter is one of understatement and humility. Hunting is about seeing without being seen. Hunting is best done quietly.

Read Next: The Critical Importance of Being Uncomfortable

Oren says

Very thoughtful and will make me reconsider why I hunt. I appreciate reading things that challenge me mentally. This fits the bill.

Luke says

Smells like jealousy to me.

Mild Bill says

Did you have to include your photo at the end of the article?

Dave says

I believe that Matt raises some legitimate concerns about hunting social media and the hunting industry as a whole. Collectively, that industry fosters an extreme culture of consumerism and unrealistic expectations for hunters new and old. I’ve been guilty of that myself.

What was so troubling about the Meateater Podcast was Matt’s tendency to paint with a very, very broad brush, and his inability to have a civil, thoughtful debate with the other people in the room. He seems unable or unwilling to allow people to finish their sentences, or to pause to reflect on counterpoints. That is called dogma. I found his responses and general demeanor to be combative and condescending not thoughtful or intellectual.

I also relocated to Montana 35 years ago, and have seen the increase in hunting pressure, but this “raise the drawbridge behind me” mentality is a pointless endeavor. Franky I find it to be incredibly myopic.

The responses regarding the impacts of the loss of 50% of the current PR funding were completely nonsensical to be frank, but that’s for another conversation. What was troubling is Matt’s apparent disregard for the egalitarian ethos of public land hunting. If a 30-year old urbanite decides to start eating antelope meat the he/she killed themselves on public land that they own and pay for, good for them!! So sorry if it inconveniences a 50 something old grump (just like me) who was “here first” . Run that one past the Crow or the Blackfeet and see what type of response you get.

I’d say Matt has some valid and important points, but they are lost in his vitriol. By the way I have three brothers, and we don’t always agree. Sometimes we even argue or debate, but i would never in a million years treat one of my brothers the way Matt treats his brother. Ouch.

L. Eskew says

FINALLY someone speaks the truth about these sickening phenomena infesting almost every corner of the west. As for my personal experience, all my elk, deer, and turkey areas are being infiltrated by naive hunters who were lured by YouTube, social media, and easy to use mapping programs. Technology is replacing woodsmanship.

andrew says

there is no way this has no comments…

Adam Cook says

Spot the fuck on !

Shane Carnahan says

Great article Matt, I agree and would add that it began in the 80’s and 90’s with the big buck videos. Though most of those hunts were on private land, they still had the influence and de-education of hunter’s from the researchers of the past and present such as yourself. Furthermore, today’s society knows more, but reality knows less, due to the dumbing internet.

Chad says

I think it would be best if Matt Rinella stays off all media forever. His complete lack of disrespect for hunters, the Meateater crew and his brother was outrageous! I do find it ironic that someone who so hates social media would take to it just to spew his own opinions. Maybe it is his turn to stop being a pouting toddler and move on!

Thank you

Al Homme says

very well written, in Montana a lot of this started in the early 90’s with a bill called H.B. 526 the MWF was a big supporter off, what this bill did was add $100.00 to all non-resident hunting lic. and create a program called “Block Management” I was on the MWF board at the time and warned them about introducing big money into wildlife managent It’s been all down hill from then I have other views on how this started the mess we’re in today

Jay says

Sounds to me like Matt needs to get with Fred Claus and find out where the next siblings anonymous meeting is. Kidding aside, although he makes some valid points, he misses more than he gets right. This article, as well as his demeanor during the MeatEater podcast just oozes a self-righteous stance born of sibling angst. We need voices like Steve’s and the rest of the MeatEater crew to show hunting in the proper light, in these times of PITA and the HSUS, if Matt were really anti-social media he’d just stfu and leave the Internet. Instead he sounds the equivalent of a vegan spouting off to a MeatEater

Ed Pfeifer says

Interesting, I think, that Matt points out that “hunting license sales increased a whopping 30% between the 1980s and 2010s” and then quickly identifies that “Also, since the 1980s, the American landscape has changed in major ways. The US population size has increased by a third”.

Am I wrong or does that represent remarkable stability instead of remarkable growth? Indeed it is a combination of off limits land and a growth in hunting commensurate with population growth that have created the overcrowding Matt hates. I hate it too.

But, to place the blame at the foot of the cadre of idiots that regard facebook as the hunter’s bible is a wrongheaded effort. The subjects are separable and should, therefore, for the sake of honest argument, be separated.

Ed Pfeifer says

Interesting, I think, that Matt points out that “hunting license sales increased a whopping 30% between the 1980s and 2010s” and then quickly identifies that “Also, since the 1980s, the American landscape has changed in major ways. The US population size has increased by a third”.

Am I wrong or does that represent remarkable stability instead of remarkable growth? Indeed it is a combination of off limits land and a growth in hunting commensurate with population growth that have created the overcrowding Matt hates. I hate it too.

But, to place the blame at the foot of the cadre of idiots that regard facebook as the hunter’s bible is a wrongheaded effort. The subjects are separable and should, therefore, for the sake of honest argument, be separated.