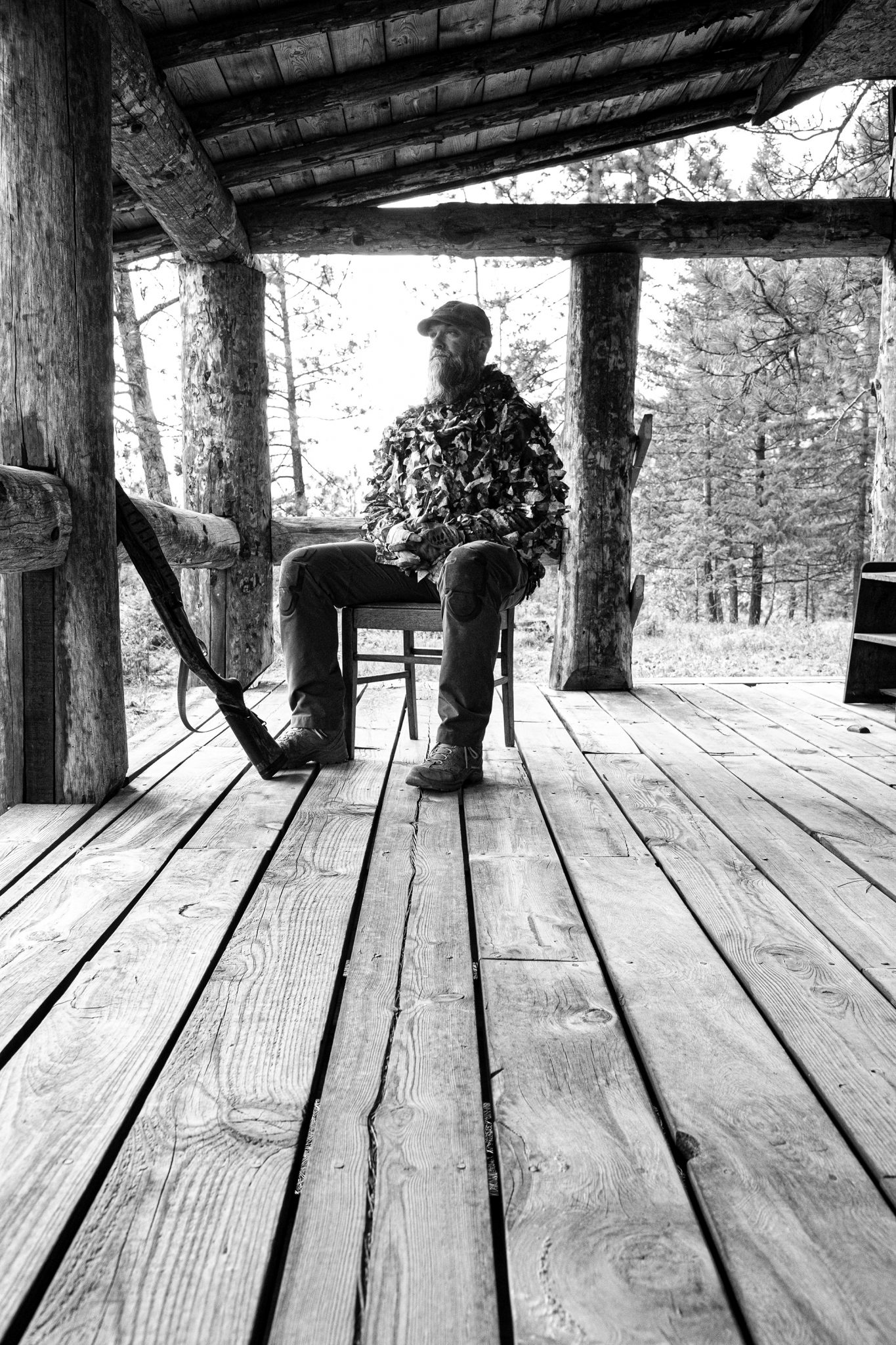

“Should we take the bird to the truck and start cleaning it; maybe get ready for the guys to return?” Andy asked me.

“How about we just sit here and look at Montana,” I said.

The thought of it being okay to be in the moment caused half a decade of combat stress to dissolve from the Marine’s face. Out here, it was okay to just sit. It was okay to just be.

When Andy and I met at the San Antonio airport, we did what any two highly trained, battle-hardened, head-on-a-swivel-type SOF dudes do: We tried checking in at American Airlines for a United flight.

To our credit, we were distracted by the excitement of traveling to the mountains. Our chatter distracted us, too: talking of the past with twinkles in our eyes — troops in contact, Andy navigating ISIS checkpoints in Iraq as a contractor, me dealing with Shia militia checkpoints in that same country but as a journalist, not a Green Beret (that time). Mainly, we were excited about the prospect of killing a turkey in Montana, but the talk went to what we knew better — what we spent our 20s knowing best — a different kind of hunting altogether.

We pulled it together, finally, and matched our United tickets to a United flight. Eventually, our chatter was silenced by the plane roaring into takeoff as we were buckled into our seats over the wing. It was like so many flights we’d been on before, only this time there was a drink cart.

“You come out to a place like this, and it fills your cup. ‘Fulfilled’ is a pretty good word that describes how I feel when I’m out here.”

We were going to Montana because a young Marine died in Afghanistan in 2010. His name is Matthew Abbate. There is a veteran organization named in his honor, Patrol Base Abbate (PB Abbate), and it had a slot for a veteran to participate in a spring turkey hunt on the Clark Fork, which is a retreat for vets to meet and recharge and heal while camping out in God’s country. Andy’s background as a Marine, first down at the line units and then on the special operations side, made him a pretty good candidate to be one of the eight mostly first-time hunters.

The clouds out of the 737’s window reminded me of the Afghan mountains — white-capped, beautiful, exhausting. We descended toward Missoula, the Bitterroot a shiny ribbon of blue with brown banks like racing stripes — a place I’ve made memories before. There’s a place on that river where I caught the biggest brown trout of my life with my father an arm’s length away.

The photo capturing that moment is framed and sitting on my desk at home. Backlit by a setting sun, my fly line tangled around my legs and stripped to its backing, both of us are only thinking about that moment. We were in the moment, for a change. There weren’t many chances to do that during eight years of constant deployments for me, first in the infantry and then with SOF, and my father carrying the weight of his youngest son living with war. But at that moment, on that river, there was only him and me — me and my dad, and the brown trout of a lifetime.

As the plane touches down, I see Andy thumbing at his phone — an inseparable appendage in this modern age. I know what he’s doing — checking in on the job he’s about to leave behind, at least for a little while.

We both check our phones and hope there’s no service on the Clark Fork.

An old buddy from my stint at the journalism school at the University of Montana meets us at the airport. He drops off a shotgun, shells, a tent, a bottle of bourbon, and a coin for Andy from his unit: the Missoula County SWAT team. Word travels fast that SOF guys are rolling through, and appreciation is often shown — an IPA bought, a scattergun lent, or with the most meaningful but simplest of gestures like a handshake.

Winding our way along the Jocko River, then the Flathead, and finally the Clark Fork, I know we’re getting close. We pass through towns that wear cold like a blanket. The type of towns that look cold in July, where the buildings on Main Street and the vehicles from the 1980s along the curbs seem like they never thawed from last winter.

People make their livings here the way they do in many small communities: off of the land, by owning the local bar or cafe, or maybe by turning wrenches or running a cutting torch. Folks in this type of town aren’t monetarily wealthy, but their smiles, words, and actions are sincere. So maybe that means they’re the richest of all. They’ve managed to hold what it truly means to be alive in their back pockets — not unlike many local people we met on deployments.

Our hunting party includes me, Andy, another hunter named Evan Smith, and our guide, Tyler Jensen. It was a pretty big crew pitted against extremely wary-eyed birds that live their lives at the same level where we’re sitting. Which happens to be the same level at which coyotes and bobcats live as well.

Two days pass with morning and evening sits. No birds showed up to our calls or to the hen and jake decoys we used to try and entice a territory-obsessed tom.

It’s time for a plan. After a fireside talk with other guides and hunters, our group decides to split forces on the third morning. Andy and I sit together watching over an open gate that led from one pasture to another; it was a spot a local farmer told us the birds liked to use instead of slipping through sagging barbed wire.

Positioned 30 meters on the high ground above our pinch-point fence-crossing ambush site, the scene feels familiar to me, and to the Marine next to me. It was cut from the infantryman’s playbook for an ambush, which Andy and I had done cumulatively hundreds of times in training and overseas. You attack your adversary at a location where you know they’ll be, and a road is perfect for an ambush.

It’s best to choose a section of road that canalizes the enemy or game, and even though this is Andy’s first proper turkey hunt, the formula makes sense to him. The result should be a dead tom — if the birds cooperate. The only thing we’re missing is a claymore mine or a set of night-vision goggles to make the situation feel even more like home.

The world around us begins to come awake — first the wood thrush, then the explosive thunder of half a dozen gobblers trying to outdo one another. Andy and I shoot each other a glance of excitement that had been perfected while working in situations where talking and making noise would have been a terrible idea. Things are looking good.

After what seems like an eternity of toms yelling thunderously at one another from the tops of Ponderosa Pines, we see our first hen walking down the road toward our ambush gate crossing. Behind her are 10 of her turkey sisters, two jakes, and one fat tom with eight inches of beard sticking out of his chest — a mature bird that would make any turkey hunter proud, no matter how many beards and spurs they’ve collected.

Our plan is coming together nicely, except the birds decide to veer around our gate crossing, which is not only in the center of our ambush but on the outer fringes of the maximum effective range for a shotgun. The turkeys peck and purr and meander 10 yards farther away from us before they cross the fence and begin feeding.

Once the big tom enters the field where the hens are, he begins to strut and push his harem around while putting on a show that you can only get in the springtime turkey woods. Distracted by the moment and relishing the adrenaline shake of Andy’s gun barrel, I come to my senses and realize we need to kill this tom. Quickly. With every step, he’s pushing farther outside of range.

“Andy?” I said.

“Yeah, man?”

“Can you kill that tom?” I said.

“Yeah, man.”

“Okay. Shoot him as soon as he gives you a shot at his head.” I said.

“Alright.”

Boom!…Boom!

The bird is hit, but it stumbles and falls into a patch of creekside willows before laying down. Andy and I scramble down the hill at a familiar pace, in a familiar way, perfected in the rocky Afghanistan mountains.

Andy is physically with me in Montana as we closed those 50 yards to reach the turkey in the willows, but psychologically he’s in Afghanistan. His eyes are wide, gun held at the modified low ready position, eyes searching for IEDs on our cattle trail, looking far for a man with an AK-47 — his RPMs are redlined. I can see it. But he is calm.

As we approach the willows where the tom had taken cover, I tell Andy to wait until he had a shot of the bird’s head so he doesn’t waste meat. The tom pops up, and Andy ends it quickly.

He crouches in the brush and pulls the tom out. Neither one of us speaks for a few seconds. I think we’re both in shock at how quickly feelings and emotions we thought we’d put to bed years ago had so easily and effortlessly flooded back. After a few moments, Andy switches into efficiency mode. Task and purpose is where a Marine’s mind always shifts.

This is the time after an ambush or an engagement with the enemy when communications to leadership are typically established, the time when ammunition is distributed, when men, weapons, and equipment are checked, and myriad other small activities are conducted at lightning speed before you quickly and efficiently leave the area ahead of any potential enemy counterattack. Andy is feeling his training kick in, but it’s at a time and in a place where that training isn’t needed.

I tell him that it’s okay to just be in the moment; the other guys are okay, and we don’t need to call them and give them our status; our equipment is okay on the hill within eyesight.

The sun fully exposes itself over the mountains, and we are standing next to a gin-clear babbling creek. Canada geese are cackling in farmers’ fields around us, we have a mature tom turkey at our feet, and the sun is casting spells off the black and purple feathers.

“When we crossed that bridge this morning,” Andy started, “when we were heading in here to hunt before daylight — that bridge took me back to a bridge we used to cross in Marjah. I always knew that it was time to go to work when we crossed that bridge.”

By the time Andy turned 21, he was a combat veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan, who would continue in that role until he was nearly 30.

“The sunrise right now feels the same as it did back then,” he says.

I ask him about that sunrise, hoping he will elaborate and maybe break through to an experience that he might need to get rid of.

“It’s similar to that feeling you get when you’re sitting on a rooftop of an objective we hit, and your team is okay. You’re waiting for extract, and you’re just fine. Because all that shit back home — bills, stress, family drama — all that crap gets tuned out on deployment,” he says. “Right now is similar to that feeling. Things are just fine.”

Andy was meshing the good experiences of now in the wilderness with the old experiences of the past, good and bad. Away from the always-being-accessible grasp of cell service and the distractions that come with it, the Marine was able to actually feel and take note of the thing that lay before him, which was the physiological effect of acknowledging and dealing with it a memory from way back when.

Andy wasn’t changed forever after a four-day turkey hunt in Montana nor was he completely relieved of all the noise he’d accumulated during many years running hard and fast overseas. He still had to keep his phone and computer close and be ever connected to social media trends and the responsibilities of managing an eight-person team for his job.

But he is better now than he was when our plane landed in Missoula.

A few weeks went by, and I hadn’t seen Andy. Then one Monday morning, I walked into the office and was greeted by his pack of mangy chihuahuas, and I knew he was close at hand. Andy greeted me with a hug as I walked past his desk and damn near picked me up.

By the hug and the shine in his eyes, I knew that we were flashing back to that stream in Montana, watching the sun peek over the mountains with a turkey at our feet.

Maybe a paraphrased Hemingway was right: “We’re all a little broken; that’s how the light shines in.” Well, the light was shining out of Andy that day. All he needed was Montana to give him a crack.

READ NEXT – Starter Kit: Gear Up for Turkey Season

Kirk says

Great article Adam! Told about as well as it could be!

Brooke churchill says

My God Adam you are a hidden gem! Well not so hidden to me any more!

What an artist you are. K forwarded this to Joe and I. I am grateful for her. I had no idea all this was under your dear hospitable humility.

This was gorgeous on all levels. From one artist to another I tip my artsy French beret to you sir! Glorious just glorious!

Warmest,

Brooke

Lucky wife of an Airborne Army Ranger