Ticks suck. It’s not bad enough that they burrow their tiny heads into places on your body that you can’t see without two mirrors and a flood light as well as spread diseases that can be potentially fatal to humans and animals — one species of the rat bastards, the lone star tick, can make people allergic to meat.

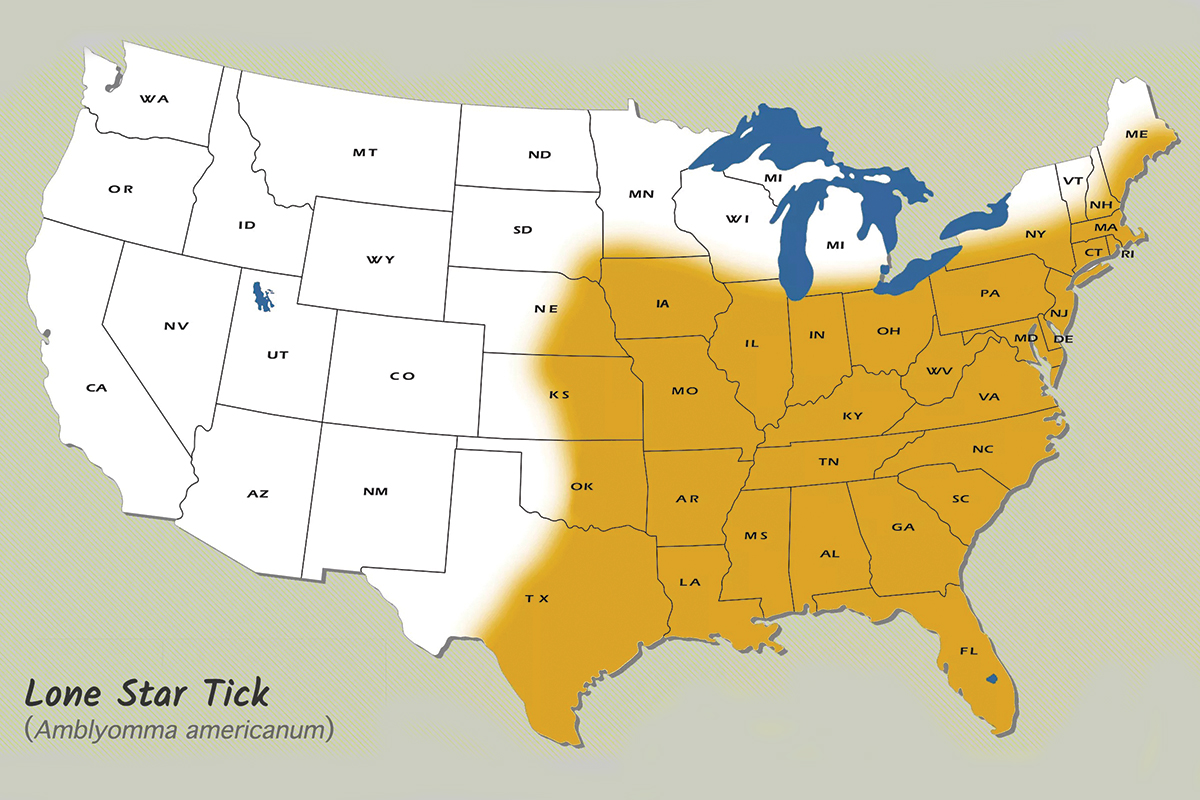

Native to much of the eastern United States and Mexico, the lone star tick — aka the northeastern water tick, turkey tick, or cricker tick — has almost reached plague status because of recent mild winters across its range.

In 2019 (the most recent data available), there were 50,865 reported cases of tick-borne diseases, up from 47,743 cases in 2018, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Between 2010 and 2018, more than 34,000 people in the United States tested positive for alpha-gal syndrome, according to a 2021 paper. That’s the disease that essentially makes a person allergic to red meat.

Even wildlife like whitetails and moose are getting hammered by ticks to the point where their populations are being impacted in some locations.

While Lyme disease has been one of the most well-known and documented illnesses that humans can get from the blacklegged tick, aka deer tick, the lone star tick is now climbing the CDC’s most-wanted list of pathogen-carrying critters with its ability to transmit alpha-gal syndrome (AGS) to humans.

Alpha-Gal and AGS

Alpha-gal (galactose-α-1,3-galactose, for you chemistry types) is a sugar molecule found in most mammals, but not in fish, reptiles, birds, or humans. Pork, beef, rabbit, lamb, venison, and products made from mammal milk (think cows) all contain this sugar molecule. It’s even been found in cat dander.

AGS is not the result of an infection. If a person with the allergy has either eaten red meat or been exposed to other products that contain the sugar molecule, they can suffer anaphylaxis — a potentially deadly condition that constricts airways and drops blood pressure — but reactions may manifest with various symptoms.

Other reactions include hives or itchy rash, nausea or vomiting, heartburn or indigestion, diarrhea, cough, shortness of breath, or difficulty breathing, swelling of the lips, throat, tongue, or eyelids, dizziness, and severe stomach pain.

Allergic reactions occur three to six hours after consuming red meat, which makes it more difficult to identify what caused the reaction than typical food allergies.

If you’ve contracted the allergy, it could take a while before you start noticing consistent symptoms. There’s no universal set or intensity of reactions — each case varies from person to person. And not everyone who gets bit contracts the allergy.

Unfortunately, there is no cure for AGS but it can be managed with the help of an allergist and a well-managed diet.

While AGS has long been known as an allergy in humans, contracting it from tick bites is a relatively recent, and scary, discovery.

Ticks that cause AGS are believed to carry alpha-gal molecules in their saliva from the blood of the animals they commonly bite, such as cows, deer, and sheep. The bite transfers the alpha-gal, causing the person’s immune system to kick in and fight the molecule.

The next time red meat or another product with alpha-gal is eaten, the immune system is again triggered to fight and the allergy presents itself.

It’s still not understood why only a small portion of humans contract the allergy after a bite. It could be attributed to differences in immune response or tolerance. It could also be that not every lone star tick carries the alpha-gal molecule.

Tick Awareness and Bite Prevention

No one wants to get any closer to these demon spawn after they’ve picked one off of their clothes or skin, but if you look closely, the adult female lone star tick has a silvery-white, star-shaped spot on her shield. Adult males have white streaks or spots around the margins of their shields.

Like pretty much every tick species, the lone star tick posts up on thick underbrush or high grass when hunting for a host. During this “questing” behavior, the tick stretches its front legs forward when it detects carbon dioxide or heat and vibration from movement.

When the unsuspecting human or animal brushes past, it saddles up for a ride — crawling around until it finds a suitable feeding spot.

According to the CDC, the best way to avoid tick bites is to pretreat clothing and gear with products containing 0.5% permethrin. Treated boots, clothing, and camping gear will remain protected through several washings.

Permethrin-treated clothing and gear, which has to meet EPA health and safety standards, is also available. Alternative treatments include sprays or lotions that contain DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE), para-menthane-3,8-diol (PMD), or 2-undecanone.

Also, using gaiters or putting pant legs into socks, tucking in your shirt, and wearing long sleeves will help minimize access points for ticks.

Once you return from a day in the field, it’s highly advisable to check your clothing and gear for ticks — also check pets thoroughly if they were out with you.

A hot shower will help get rid of ticks that might not have dug in yet. It will also give you an opportunity to check likely tick bite spots on your body, including under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, back of the knees, in and around the hair, between the legs, and around the waist.

With a little prep and mindfulness, you can keep yourself better protected from these microscopic assholes and not have to worry about giving up your God-given right to grill and eat red meat.

READ NEXT – Vermont May Issue More Moose Tags to Combat Winter Tick Menace

Comments