The sounds of drilling and blasting amid the big rock cliffs over the Tsavo River for the Kenya-Uganda Railroad didn’t scare off the big cats of Africa — it did just the opposite. At night when the bridge construction stopped, and the laborers slipped away into their rickety palm huts to rest, the silence was often punctuated by screams.

It was March 1898 when the terror became too much. Construction of the British colonial railroad under the hot African sun stopped. The disappearances of workers paralyzed all work. And the hunters lurking in the darkness of the Kenyan savannah became known as the “Man-eaters of Tsavo” for their nine-month-long reign of terror. Here, humans were not at the top of the food chain. The two male lions, which went mostly unseen, were named the Ghost and the Darkness.

The man-eating lions had no manes.

For eight years, Bruce Patterson, the curator for the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, researched why the man-eating lions of Tsavo were maneless and discovered a hypothesis.

“Mane length and density were inversely correlated with temperature; color variation was unrelated,” he concluded in his research paper. “Mane development was correlated with January but not July conditions, suggesting a stronger response to cold than to heat. Climate-induced variation in manes of captives accounted for up to 50% of variation seen.”

In layman’s terms, the lions of this region do not have manes because it was hot. Damn hot. It’s an interesting variation, as elsewhere manes are believed to help lions survive territorial disputes with other males, as a kind of head and neck armor.

In the lions’ rampage, 135 humans were reported eaten.

That’s a lot of eating of humans. Lt. Col. John Patterson (no relation to the Field Museum curator) published the book The Man-Eaters of Tsavo and Other East African Adventures in 1907. He perhaps sensationalized the numbers — to as high as 135 humans eaten, which likely helped sell copies of his book and led to three Hollywood movies. The Ugandan Railway Co., however, reported 28 dead workers. More than a hundred years after the story, using chemical analysis of the lions’ hides, the Field Museum suggested the more accurate number to be 35 people eaten, 11 by one lion and 24 by the other.

Scientists claim the lions hunted humans because they were easier to chew.

Not only are we humans easier to catch, but the very makeup of our bodies is more appealing to lions who want to put in less work to kill and chew their prey. The Field Museum’s Bruce Patterson and Vanderbilt University’s Larisa DeSantis published a study in the journal Scientific Reports of the teeth and jaws of known man-eating lions compared with wild-caught lions. At a microscopic level, they found that for the man-eaters, hunting live humans might have been preferred over gnawing the bones of dead animals, which is much harder on the teeth.

Patterson further examined the skull of one of the man-eaters from Tsavo, and it showed a severe tooth abscess. Broken teeth are the norm for lions, as their faces are the target of defensive kicks by prey. The pus pocket might have made it too painful for the lion to take on larger prey.

Other factors included a severe drought in the region, a virus called rinderpest that killed prey like buffalo — and a caravan route that the railroad followed. “This caravan trail would have left a steady trail of dead and dying slaves,” Bruce Patterson noted. So, the lions may have learned to eat human flesh by scavenging the bodies. Zoologists in 2001 wrote a report in the Journal of East African Natural History stating that when lions attack people, they typically eat the “large fleshy parts, including the buttocks, thighs and arms.”

Lt. Col. Henry Patterson stopped work to kill them.

“Give me snuff, whiskey, and Swedes, and I will build this railroad through hell,” Minnesota railroad baron James J. Hill once famously said. Lt. Col. Henry Patterson might have said the same. Patterson had a lion problem delaying his railroad, but the British military officer, with experience killing tigers in India, had a plan.

In December 1898, Patterson’s first attempt at killing the lions was unsuccessful. Summoning the workmen at their camp to gather tin cans and noisy instruments, he had them form a semicircle and advance into the bush. Patterson positioned himself behind an ant hill and waited for the lion to walk past. The lion came within 15 yards of his position, but Patterson’s double-barreled rifle misfired. Flustered, he hadn’t fired the left barrel. But the noise created by the workmen had disoriented the lion, giving Patterson enough time to shoot again. This shot hit its target but didn’t wound or even kill the lion.

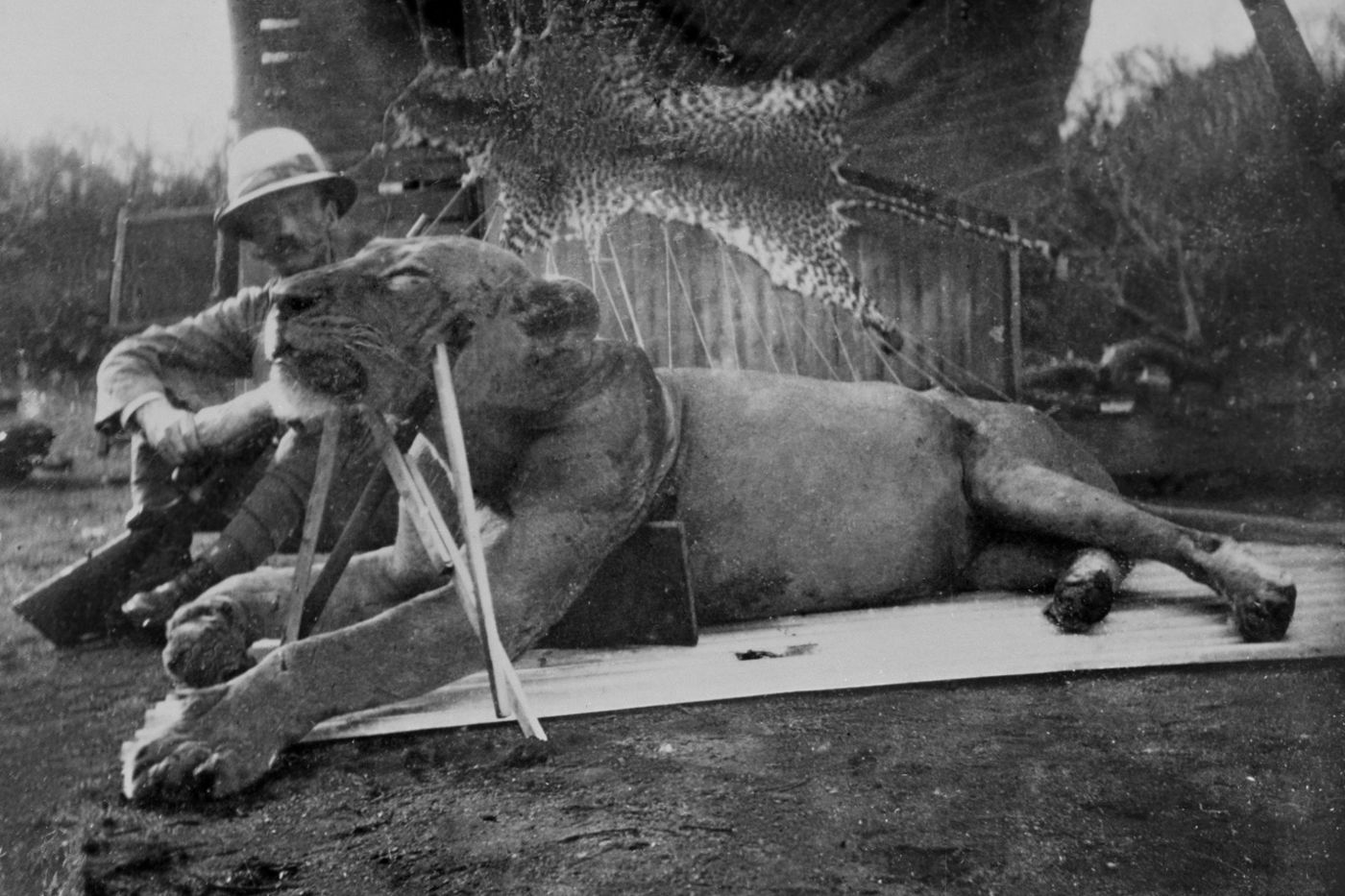

Upon nightfall, Patterson built an improvised treestand with a chair perched above the ground and set a dead donkey carcass as bait. He killed the first man-eater with two bullets from his rifle. The second man-eater’s death was perhaps even more dramatic. Patterson used goats as bait, but in the pitch dark, he fired bullets wildly. He set up another blind above goats and waited again. When the lion approached, he fired his smoothbore and connected. The lion dashed into the bush and died. When the story got out, Patterson became an international hero.

You can still see the man-eaters in Chicago.

Patterson initially used the two dead lions as exotic floor ornaments. In 1924, he sold the skins and skulls to the Field Museum of Natural History in exchange for $5,000. Since the hides had been made into rugs, when it came time for a Field Museum taxidermist to full-body mount them, the lions ended up much smaller in size than they were in real life. The beasts that once led a reign of terror in Kenya now delight children and museum visitors in Chicago, Illinois.

People are still being eaten alive in Tsavo and across Africa to this day.

In 2010, Paul Raffaele wrote a piece for the Smithsonian Magazine about his travels following Bruce Patterson to Kenya to explore the real story. When he arrived in the capital city of Nairobi, a lion had just killed a woman, and only weeks earlier a cattle herder was killed and eaten.

“That’s not unusual at Tsavo,” said Samuel Kasiki, the deputy director of biodiversity research and monitoring with the Kenya Wildlife Service. It’s not unusual for the continent of Africa either. A study published in Nature in 2005 counted nearly 600 deaths and 300 people injured by lions in Tanzania alone since 1990. “There’s really something about ‘man-eaters’ that puts people in their rightful place,” said Bruce Patterson. “Not at the helm but a couple of notches down.”

Read Next:

Maureen says

Last point – people are still being eaten alive in Tsavo to this day. That’s a whole load of bullshit.

While the other points are okay with a few inaccuracies, your last point waters down your article making it pathetic. Your sources of information have distorted the truth completely.

I live in Nairobi and travel to Tsavo often for work. There have been NO REPORTS of a woman killed by a lion in Nairobi, neither have there been other incidences where lions have attacked and killed LET ALONE EAT a human being in Tsavo.

Your disgusting attempt at making Kenya (or what you would call Africa) seem like a jungle is just that. Disgusting.

Now before you write such articles, would you take a moment and verify your story?

Michael says

Boy… You need to coll down, my friend. I hope you are not saying that lions don’t kill and eat humans in Kenya because that would be a ridiculous statement. If there are wild lions or other dangerous animals running freely and sharing habitat with humans their bounds to be attacks on humans. Many mountain lions are regularly being sighted by my house and I live in Laguna Beach, California. If those mountain lions kill and eat humans in the middle of a cosmopolitan city why would a lion with many folds bigger and heavier than mountain lions would not take advantage of an opportunity in the Jungle or Bushes and attack people who must fetch water, wood, or other daily needs? You seem to take offense to this fact and seem to correlate attacks with being less affluent.

Tom Smith says

While it might be rare, news reports show that it happens on occasion. It’s not a put-down of Africa as a whole or Kenya in particular if a wild animal kills a human. In the USA, we have occasional killings of humans by mountain lions, grizzly bears, and buffalo. That doesn’t make it an attack on America, just a face about America.

CNN reported in 2015 that a lion killed a woman while she was taking photos of them. In my opinion, her desire for a photo overrode her common sense to roll up her window. It’s not a reflection you, Kenya, Africa, or even the lion if someone was doing something stupid. It was her fault for not having enough situational awareness.

Source: https://www.cnn.com/2015/06/08/world/africa-lion-attack-photo/index.html

Hillary Hoban says

I enjoyed your article, thank you. What you’re saying about man eating lions makes sense, statistics accurate or not. The only reason I happened upon this fine article at all is I’m watching The Ghost and the Darkness (1996). I’ve always wanted to visit Africa. Possibly Maureen knows some type of mandatory training for lions so they no longer engage in such repulsive, socially unacceptable behavior?🤔