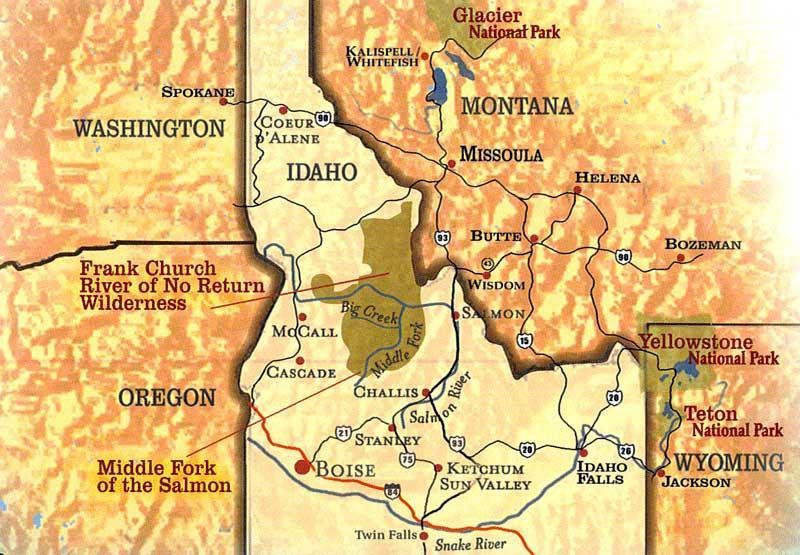

Kyle Lamb won the lottery this year. For more seasons than he can remember, he’s played the game and come up empty-handed. This year, though, Lamb drew a coveted Idaho bighorn sheep tag and was headed to the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness to fill it.

A die-hard archery elk hunter and decorated Special Forces veteran who fought in the Battle of Mogadishu, Lamb is no stranger to hard work under extreme conditions in unforgiving locations. He welcomed the fact that he was in for soul-grinding climbs, brutal descents, and impossibly long stalks, possibly with no full-curl payoff.

Luck of the Draw

Big game states like Idaho, Wyoming, New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, and even Nebraska hold lotteries for a finite number of tags. Idaho’s lottery system for bighorn sheep is different from other states because there are no preference points or bonus points. There is also no distinction between resident and non-resident hunters. This means everyone in the country has the same odds of drawing a tag. You pay your money and take your chances.

There were only 76 tags available for Rocky Mountain bighorn in Idaho this year and 16 tags for Sierra Nevada sheep (formerly known as California sheep). Both are sub-species of bighorn sheep.

In Idaho, you’re only allowed to kill one of each in your lifetime.

Waiting Game

Base camp for the hunt was a 6-mile downhill hike from the trailhead. They spent the first few days on ridgelines and rocky outcroppings glassing for movement; only one mule deer was spotted. Early on the morning of their fourth day, Lamb and his guide, Kyle Allen, climbed back up to a ridgeline about 1,000 yards above camp where they had set up a spike camp and split up to glass the valley for movement in the morning sun.

“I sat down with my walking stick and my binos on top of them for some support. I started glassing, and oh man, there’s another mule deer. I watched him for a while, and I thought, that animal just doesn’t move like a mule deer. Now I’m no sheep expert. I’m not. I’m not a sheep hunter. I’m an elk hunter. But I kept staring and really wanted to make him a sheep. All of a sudden he walks up onto a little knoll and steps into the sun. Even from as far away as I was, there was no doubt that it was a bighorn ram.”

Lamb found Allen and got him looking at the spot where he last saw the sheep. Of course, he wasn’t there. But then Allen found the animal, and then another.

“Right in the shadows by one of these rock slides, one of the bighorns that had laid down in the shade, he was able to glass him up in the spotter. Allen said, ‘Oh yeah, there’s another one over there.’ By the end of it, we had five of them in the glass.”

Now that they had sheep, it was time to make a move. Lamb and his guide packed up all their gear and humped back to basecamp, where they were able to get eyes on the sheep once again and put them to bed that night. They had a good base camp meal and racked out.

After a short dawn hike to a glassing spot, they located the group and culled their gear to the bare essentials for the brutal climb they had ahead. The main guide in camp stated the obvious: Gonna have to get above them.

“I’m looking at this mountain, saying, ‘I’m sick of climbing these hills,'” he laughs. “I’m a flatlander from South Dakota.”

Lamb Closes the Distance on Sheep

An almost 3,000-foot climb put the two at the same altitude as the sheep, and they set up camp. They didn’t get eyes on the sheep but felt confident that their position was good. The next day was spent watching for any sort of movement and hoping the sheep would feed their way through. Nothing.

The next morning they broke camp and moved farther above where they had last seen the sheep from the valley. There’s no rushing a stalk like this with so much to lose. Bighorns are not easy-to-find animals in the first place, and they’re damn near impossible to get back on if they bust you and bolt. The two set up shelter and spent one more night, planning on making a move down into them first thing in the morning.

“We knew where we’d seen them,” he said. “We had to get back in that vicinity. It’s really steep, and we’re thinking that we’re still probably a little bit high, so we start working our way down until we finally get eyes on them. We’re within about 400 yards of these rams — and they’re above us.”

Lamb knew his max range limit was 750 yards, so he was very confident at this distance. He snuck into a position to set up.

“Every single rock there is sharp. So I’m trying to get my little piece of Thermarest in place to sit on. I see them kind of playing around on this hillside and then the wind shifted from behind us and blew right up in this little canyon. I didn’t know how spooky they were going to be, but they just disappeared.”

The terrain on these rocky mountainsides plays hell with visibility because there is so much ragged stone. Moves as small as a few feet in any direction can drastically change the entire field of view. Lamb backed out of his spot and retreated 30 yards up their side of a small ridge to where he and Allen had dropped their gear.

They figured that the rams slid into the canyon just opposite them, so they moved as carefully as possible to get a look.

“All of a sudden, we saw them. There were three shooters and two banana horns, you know, just young rams. Again, I’m not a sheep hunter, but two of them were very good, and one of them was really, really good. He looked old. He was broomed off and had a bad leg. We couldn’t figure out what was wrong with him, but he had a little bit of a limp.”

“There was a distinct difference between number one, number two, and number three. So number one kept his mass all the way down and around in his curl. He actually looked thicker down the horn than he was at the base, which is crazy.”

Lamb pulled out his SIG Sauer CROSS in 6.5 Creedmoor topped with Leupold VX-6 2×12 glass, chambered a Hornady 143-grain ELD-X, and settled into his rest. Allen ranged the ram at 220 yards.

“At 220 yards, there’s no dial-in. I needed to hold about one minute high. 6.5 Creedmoor is still pretty flat at 200 yards. I didn’t want to be cocky because whenever you get cocky, that’s when you screw stuff up. I checked everything, tried to look to see if there was any bad wind, but it was 200 yards so even a pretty significant wind isn’t going to do much.

“So I cracked off a round and had a very good wallop sound come back. I saw the sheep jump forward and then he disappeared, but I heard all these rocks falling, and it was just total mayhem. We heard the rocks and the shale falling below us and I thought, ‘Well, that’s a dead sheep.’ I mean, all that racket, that’s got to be a dead sheep.”

They packed their gear, and Lamb kept his rifle out for the slow scramble to the bottom of the shale slide.

Zero to Hero on the Bighorn of a Lifetime

Almost every hunter has had that moment where they walk up to the spot that their arrow, slug, or bullet was supposed to have hit its target and put the animal down, only to find nothing, or worse, evidence of a gutshot. Lamb and his guide were in the thick of that moment.

“I’m looking around and seeing a little bit of disturbed shale but there’s not a drop of blood. The guide started climbing up to where I shot the ram and I was working my way up a different line just looking for anything. I get up to him, and he says there are guts up there. I’m thinking you got to be kidding me. I felt great about my shot, but man, anything can happen. I mean, we’ve been up here a long time. Even if you think it’s perfect, you just never know what can go cattywampus on you.

“So I thought at that point that I gutshot this thing. So we started walking down this drainage because if this joker’s hurt, he’s gonna keep going downhill. Sure enough, those tracks just kept going down and down, and then they cut across the hill. So I cut with the tracks. Kyle kept going farther down. We slowly worked our way down to a spring and, man, I was just heartbroken. I thought I’d find this joker just balled up down there and that’d be it.”

After a satellite message with the head guide told them to just leave him be and go back in the morning with more men, Lamb and Allen decided to take one more run up to where they last had blood. A 2-hour climb brought them back to just below the outcropping that the ram was standing on.

“I was looking up at this cliff and thinking, how the heck am I even going to get up there to where he was standing? I’m gonna have to drop my pack to crawl up there or something. I was about to do that and I heard [Allen] say, Hey, man, I found something up here.”

His guide had gone all the way around this knoll and was well above Lamb. There was a rock slide on the other side of where the ram was shot, but when the men first passed through, they hadn’t tried crawling up higher.

“When I shot he made two jumps and dropped at the top of that rock slide, 15 yards from where I shot him to where he laid. I got up to [Allen] and saw this thing laying up in the rocks and it looked like a dinosaur. This joker was just such a huge, huge ram. I went from zero to hero really quick.”

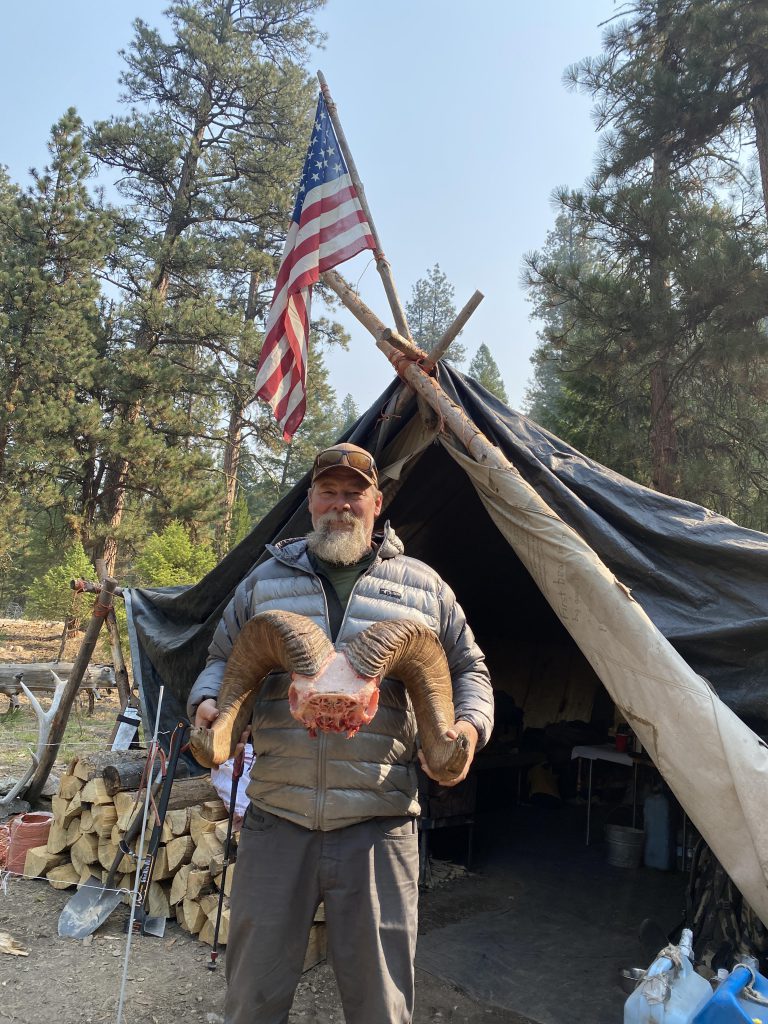

Kyle Lamb’s Sheep

The old warrior’s horns were broomed at the ends, and all of his teeth were gone. As for his limp, one of his hooves was still busted up from an old injury. He taped out at 178 6/8 inches and was estimated to be about 10 years old. Another guide had made his way from camp up to them and helped cape, quarter, and pack the old ram out.

“At one point there we were huffing and puffing and standing there and my guide — he’s like a 25-year-old kid — said, ‘You know stuff like this, these make great memories when you’re suffering like this.’ I said, ‘Hey, bro, check it out. I’ve had enough of these great memories,'” Lamb said. “I’m at the point where I don’t need any more suffering for great memories.”

As far as his favorite hunts go — and he’s been on more trips than he can count — Lamb said this is definitely in his top five.

“I don’t like the word ‘epic.’ But this was truly epic.”

Read Next: The Art of Conservation: Yeti Presents’ Wild Sheep’

Comments