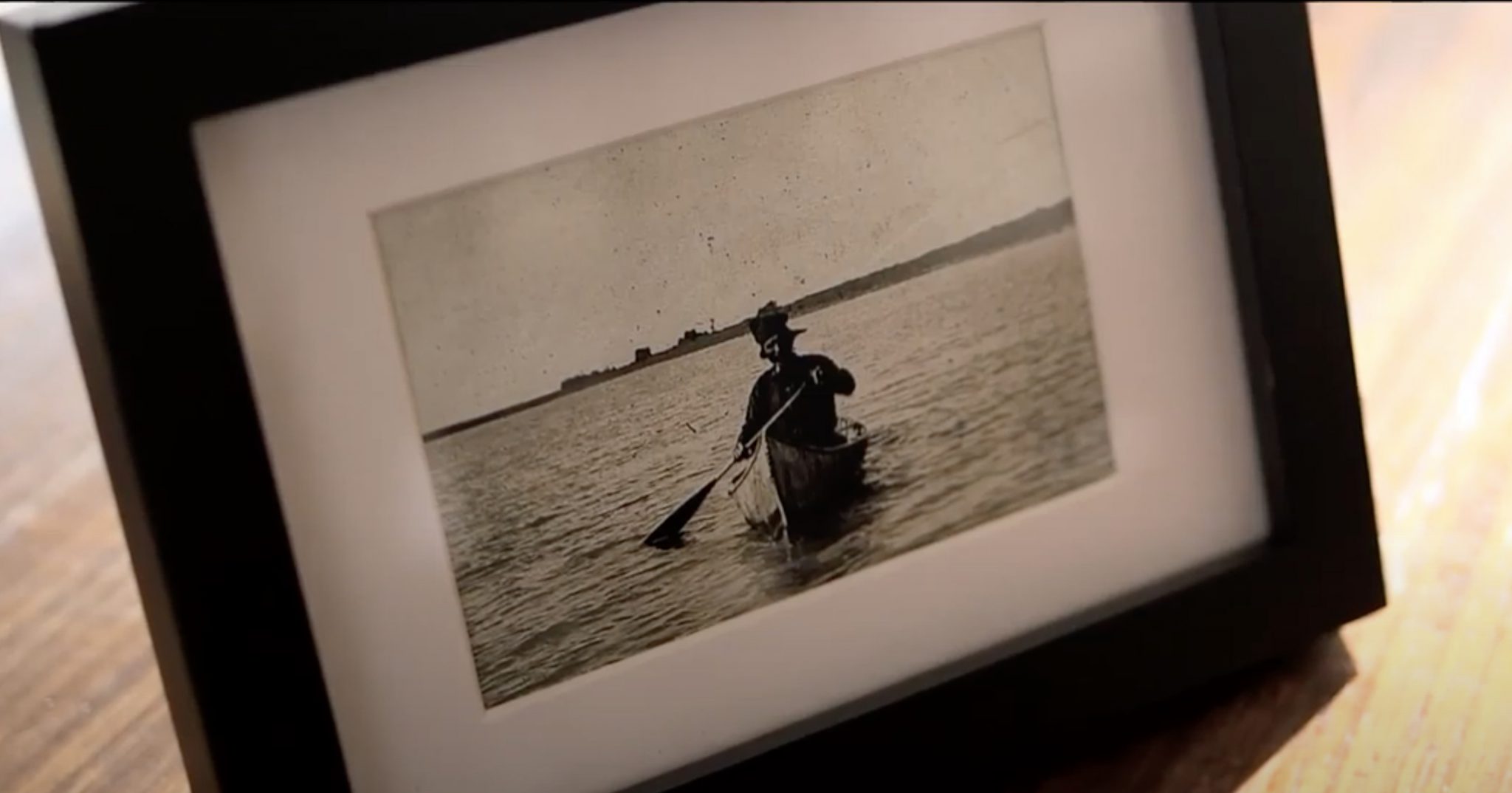

Conformity wasn’t an accepted word in the vocabulary of Kate Rice. The blond beauty had all the basics and intangibles to lead a safe and risk-averse life. She was born to wealthy parents, but her father, Henry Lincoln Rice, may be to blame for introducing her to a lifelong passion for exploration in the outdoors. He taught her from an early age how to live off the land. They went on hunting and camping trips together. Their method of travel was by canoe down the St. Marys River between Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and the Canadian province of Ontario.

In the classroom she excelled. The University of Toronto rewarded her academic achievements with two scholarships, and in 1906 she graduated with a bachelor of arts in mathematics. She had six years of teaching experience in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta — yet there was a void that encouraged her to leave behind her comforts and enter the wilderness.

In those days women didn’t have the same privileges as men, but Rice didn’t care. When rules and regulations declared that women weren’t allowed to homestead, she insisted that the land belonged to her younger brother, Lincoln. The clever misdirection on paper allowed her to explore The Pas in Northern Manitoba without worry.

She immersed herself in the knowledge of the local First Nations tribal people. They taught her their Cree language and even gave her the name Mooniasquao, or “White Woman.” Her familiarity with their bushcraft would be a great asset when she left her cabin alone in the woods to prospect for gold and other minerals.

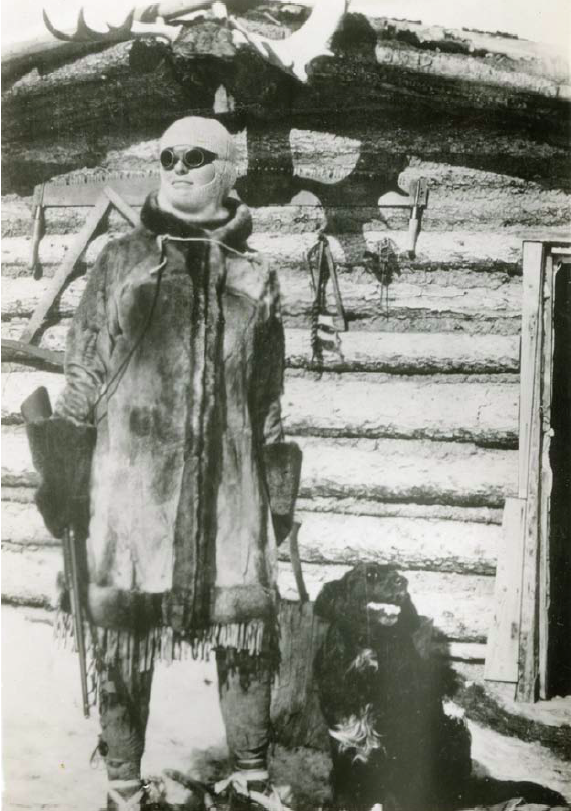

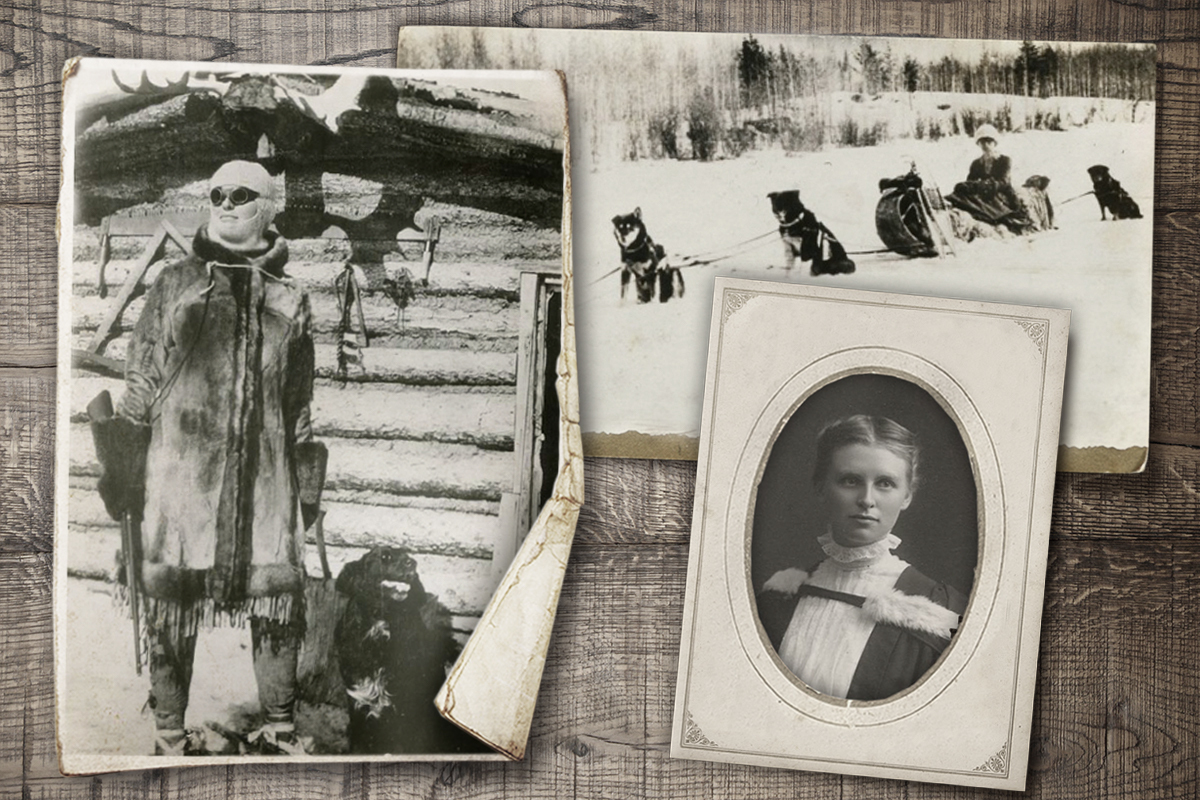

In 1914, she discovered zinc and vanadium at Reindeer Lake, located in northwest Manitoba. In her travels, dressed from head to toe, she wore a thick fur coat with gloves, long boots, goggles, and a white ski mask. She carried a shotgun to hunt game, sometimes animals as large as moose, then dressed the meat. Rice also packed snowshoes in case they were needed for the occasion. Whether it was in a canoe on the river or through the snow with a dogsled team, Rice was more than equipped to handle the tasks only men before her had previously taken on.

Even more so, throughout her some 50 years as a professional prospector, Rice staked claims of gold, had the first 16 nickel and copper properties on Rice Island near Wekusko Lake, and became an entrepreneur. She launched the Rice Island Nickel Mining Co. in 1928, but her business partners had a falling-out that quashed a burgeoning money-making effort. Still, Rice was instrumental in bringing the mining industry to local towns such as Snow Lake, Flin Flon, and Thompson. Through her influence, these towns are now on the map and her discoveries of valuable mineral deposits would help enrich their economies for years after her death.

The woman known to the world as “Canada’s first woman prospector” was a trailblazer and a historical role model. Her legacy inspired dozens of women in Winnipeg to take prospecting classes in the 1940s and ’50s. In 2014, she was inducted into the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame.

“If women could understand the thrills of prospecting there would be lots of them doing it,” Rice said, reflecting on her life experiences. “No woman need hesitate about entering the mining field because she is a woman — it isn’t courage that is needed so much as perseverance.”

Comments