Near sunset on Saturday, a team of 10 Nepalese Sherpa climbers paused just short of the summit of the world’s second-highest mountain. Even amid temperatures dipping below minus 60 Fahrenheit, and with the lethal promise of the looming night on the jagged horizon, it was important for the team to reach the peak together. And so they did. At 5 p.m. the group trudged up those final 30 feet while singing the Nepali national anthem until there was nowhere higher to go — thereby completing the first-ever winter ascent of K2, the so-called “savage mountain.”

“We are proud to have been a part of history for humankind and to show that collaboration, teamwork and a positive mental attitude can push limits to what we feel might be possible,” Nepalese climber Nirmal “Nims” Purja, who was among Saturday’s summit team, wrote on Instagram.

A former Gurkha soldier and British Special Forces commando, Purja was a guiding force on the unified Nepalese climbing effort. “Standing on the summit, witnessing to the sheer force of the extremities of mother nature was exhilarating,” Purja later said. “We set out to make the impossible possible and we are honoured to be sharing this moment, not only with the Nepalese climbing community but with communities all across the world.”

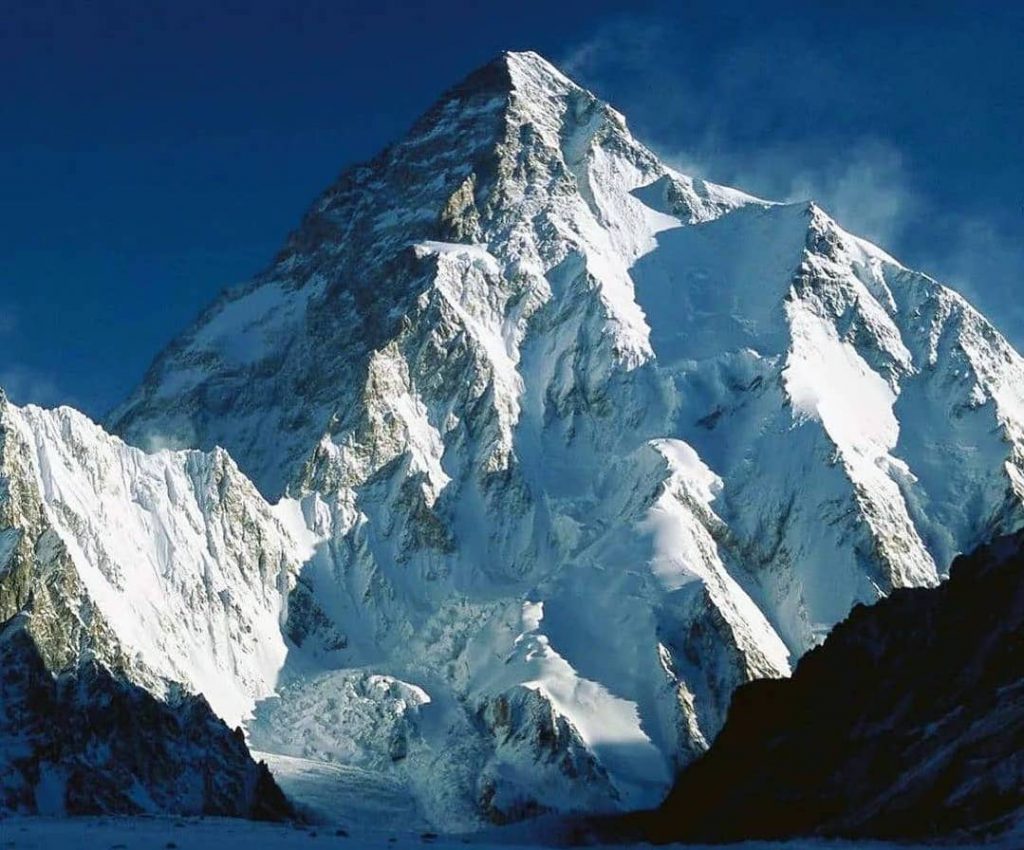

Although 28,251-foot-tall K2 is nearly 800 feet lower than Mount Everest, it is widely considered by mountaineers to be a much greater challenge than the world’s tallest peak. More than 4,000 people have reached the summit of Everest, whereas only 367 people had climbed K2 as of June 2018, National Geographic reported. And for every three climbers who reach the summit, about one dies.

Mountaineers viewed a winter ascent of K2 as the last great unaccomplished feat among the world’s highest mountains. Among the 14 mountains higher than 8,000 meters, about 26,250 feet, K2 was the only one that had not yet been climbed during winter. This year, the allure of this last great first in Himalayan mountaineering drew some 60 climbers among four different teams. Among them is a 35-year-old American adventurer named Colin O’Brady, who completed the world’s first solo, unsupported, and human-powered crossing of Antarctica in December 2018.

In a decidedly modern touch to a historic mountaineering achievement, and thanks to the satellite communication equipment he’s lugging up the mountain, O’Brady took to social media while on K2’s slopes to congratulate the Nepalese team. “Witnessing strength and skill at the highest level is a beautiful thing. Huge congratulations to all ten men and to the country of Nepal,” O’Brady wrote Sunday on Instagram.

Climbing with a longtime friend named Jon Kedrowski, O’Brady marketed his winter attempt on K2 as “The Impossible Summit.” With the victorious Nepali team having already left base camp by helicopter, O’Brady was still gunning for his own summit push, as of this article’s publication. Yet with winds on the summit exceeding 100 miles per hour, and with windchill temperatures dipping down to minus 100 Fahrenheit, he and Kedrowski were reduced to waiting for better weather at base camp.

“Ultimately the mountain will decide,” O’Brady wrote. “For now we sit here in our dome tent, listening to the wind build, waiting patiently.”

A team of Italian climbers first climbed K2 in 1954, just one year after New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay reached the summit of Mount Everest. American mountaineer George Bell, who was part of an unsuccessful American summit bid in 1953, called K2 “a savage mountain that tries to kill you.” An avalanche on K2’s notorious “bottleneck” section led to the death of 11 climbers on one day in August 2008.

Dramatically rising above Pakistan’s Godwin-Austen Glacier, K2 is an imposing pyramid of rock and ice. The mountain’s flanks are steep and terrifyingly exposed, requiring a technical proficiency from climbers well beyond that of Everest. The chances of rockfalls and avalanches are ever present, casting climbers under a constant shade of potential, unseen death. Thus, climbers on K2’s vertiginous flanks never know when a wave of snow or a random hunk of rock has them in its sights. They can only hope that the luck of seconds and inches is on their side. Adding to these objective dangers, K2 is located at the northwestern limit of the Himalayas in Pakistan’s Karakoram range. Situated farther north than Everest and unaffected by the predictable patterns of India’s monsoon, the weather on K2 is generally colder and less predictable.

As if K2 isn’t daunting enough in temperate weather, climbing in winter further compounds its challenges. The problematic weather turns truly atrocious. Winds whip to hurricane force and temperatures drop to Arctic levels. To make matters worse, the lower barometric pressure in winter further reduces the amount of oxygen available for climbers to breathe.

“The margins of error are almost non-existent, the smallest mistake can have catastrophic consequences,” Purja writes on his personal website, describing the perils of a winter ascent of K2.

After serving six years as one of Nepal’s vaunted Gurkha soldiers, Purja spent 10 years in the United Kingdom’s Special Forces. He was the first Gurkha to serve with the UK’s Special Boat Service — a unit with a mission set roughly equivalent to that of the US Navy SEALs. In 2019, the Nepali commando summited the world’s highest 14 mountains in just six months and six days, beating the existing record by more than seven years.

Describing the Nepalese team’s historic winter ascent of K2, Purja wrote on Instagram: “The decision to hit the summit was a tough one. It was one of the hardest push ever, no denial. There had been close calls where team members nearly turned around due to the extreme cold. But everyone was pushing themselves to the edge of their limits for a purpose; a common goal, to make the K2 winter happen, to make the last greatest mountaineering challenge happen, with a positive power and honour.”

A 1987 Polish team was the first to attempt a winter ascent of K2. There were a handful of other attempts over the intervening decades, yet, until last weekend, no winter expedition had ever made it higher than about 25,000 feet on K2 — nearly two-thirds of a mile short of the summit. This year, the 10 Nepalese climbers, who were originally divided among three different teams, ultimately decided to unite their efforts to claim the historic accomplishment in their country’s name.

They worked together to string fixed ropes and establish high camps up the Abruzzi route — the standard line up the mountain, which was taken by the successful Italian expedition in 1954. And as a group, the Nepalese team topped out together. Yet, by reaching the summit at sunset, the climbers had committed themselves to a perilous nighttime descent back to the safety of their highest camp, which was located on the mountain’s shoulder at 24,934 feet. Nevertheless, they successfully threaded the needle, so to speak, and some 24 hours after reaching the summit all 10 members of the Nepalese team had reportedly made it back to base camp, marking the safe conclusion of a historic accomplishment.

For his part, O’Brady highlighted the historical justice of the last great mountaineering first being accomplished by the very people who had enabled many Western climbers to achieve their own Himalayan ambitions.

“I can’t think of a more deserving group to achieve this unparalleled feat,” O’Brady wrote on Instagram. “Historically, Nepalese Sherpa have been the backbone of most major high altitude climbing expeditions, but too often their names have been passed over by history. It’s a monumental moment in climbing history for these 10 Nepalese men to claim ‘the last great prize in mountaineering.’ Well deserved! Immense congratulations.”

Nepali Sherpas are famous for their high-altitude stamina and strength. On commercial expeditions to Mount Everest, Sherpa climbers and porters do much of the hardest work, establishing and supplying camps up the mountain and establishing fixed ropes along the entire route to the summit. After a deadly avalanche on Everest in 2014, Sherpas working for the myriad commercial expeditions on the mountain went on strike, demanding better working conditions and improved benefits for the families of those Sherpas killed while on the job. Amid that backdrop, Saturday’s historic first ascent of K2 was generally viewed by many in Nepal as a national accomplishment and a testament to the skill and stamina of Nepal’s most elite climbers.

“For decades, Nepalis have assisted foreigners to reach the summits of the Himalayas, but we’ve not been getting the recognition we deserve,” Kami Rita, a Nepalese climber who has summited Everest a record 24 times, told Agence France-Presse in an interview.

Despite last weekend’s historic accomplishment, K2’s lethal law of averages remains an inescapable certainty. As if to underscore the mountain’s fickle temperament, a 49-year-old Spanish climber named Sergi Mingote fell to his death on Saturday while descending the lower flanks of the mountain to base camp.

Mingote was an experienced high-altitude mountaineer who was on a quest to climb all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks. He was reportedly trying to climb K2 without supplemental oxygen or any logistical support — an astounding feat known in mountaineering circles as climbing by “fair means.”

Speaking about Mingote, O’Brady wrote on Instagram: “Though I didn’t know him well, his tent is directly across from mine in basecamp and we chatted most days. The news of his accident is very fresh and I’m still processing all that this means. It is heartbreaking. Thoughts and prayers go out to his family, friends and loved ones.”

Comments