This was no ordinary winter on K2, the world’s second-highest mountain.

For the first time ever, a team summited 28,251-foot-high K2 in winter, marking the achievement of the last great first in Himalayan mountaineering. The successful team comprised 10 Nepalese climbers who sang their country’s national anthem up the final few steps. It was a particularly symbolic triumph for a group of climbers — Nepal’s Sherpas — who have done so much to help realize the mountaineering dreams of generations of Westerners.

“Brother to brother, shoulder to shoulder, we walked together to the summit whilst singing the Nepali national anthem,” Nepali climber Nirmal Purja, who was on the summit team, later posted on Instagram.

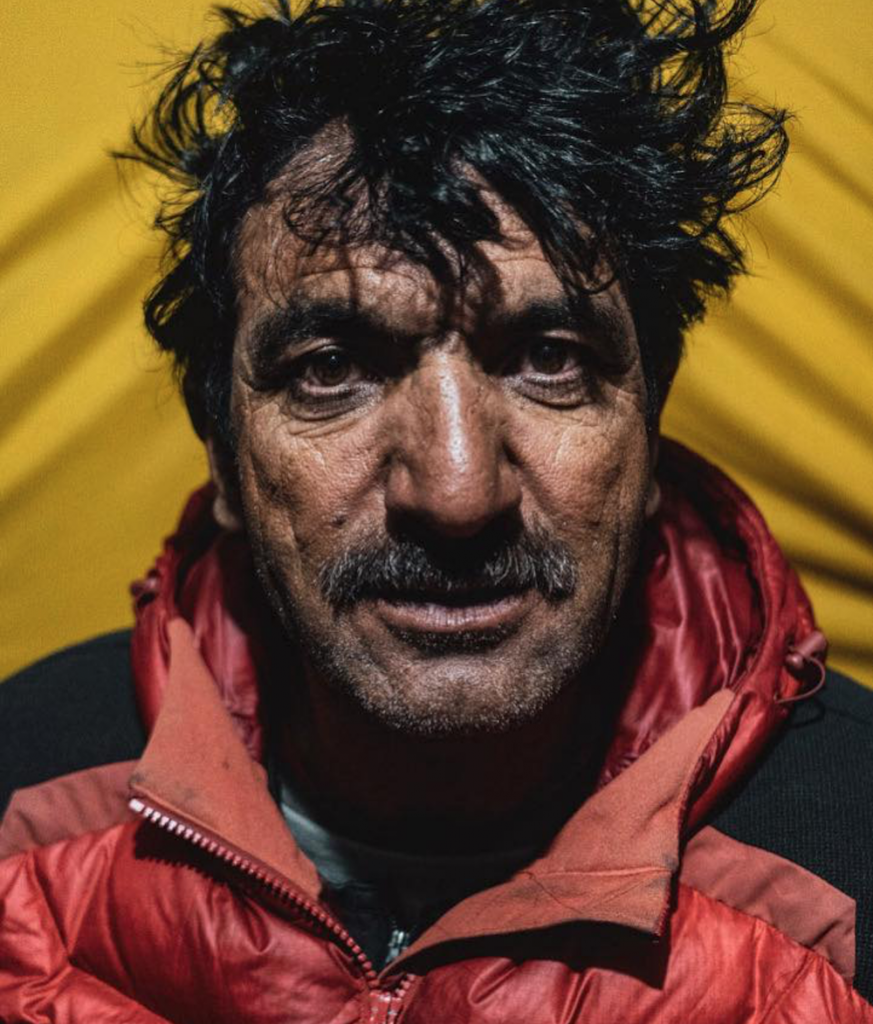

The historic achievement was, however, quickly marred by tragedy. On Jan. 16, the same day the Nepalese team summited, a 49-year-old Spanish climber named Sergi Mingote fell to his death on K2 while descending to base camp. It seemed, at the time, a grim postscript to an otherwise epic day. In truth, however, Mingote’s death was simply the opening act in a series of calamities that would, at least in the short term, mar the historic performance of the Nepali climbers.

K2 is not known as “the savage mountain” for nothing. And this winter, like any other season on K2, was not innocent of tragedy. Three mountaineers disappeared on Feb. 5 while heading for the summit. Two others, including Mingote, died during falls on relatively benign portions of the climb.

In an Instagram post describing his retreat to base camp on Feb. 5 after an unsuccessful summit bid, the American adventurer Colin O’Brady wrote: “The weather was calm, my mind was at peace, I was in awe of the expansive natural beauty all around me. Little did I know over the next 24 hours I’d lose 4 friends and my life would never be the same.”

Although 28,251-foot-tall K2 is nearly 800 feet lower than Mount Everest, it is widely considered by mountaineers to be a much greater challenge than the world’s tallest peak. More than 4,000 people have reached the summit of Everest, whereas by June 2018 fewer than 400 people had climbed K2. American mountaineer George Bell, who was part of an unsuccessful American summit bid in 1953, called K2 “a savage mountain that tries to kill you.”

Apart from the objective dangers of avalanches and rockfalls that one encounters in any season, climbing K2 in winter is even more fraught with danger — the cold, above all, which can dip as low as minus 60 Fahrenheit with the wind chill. Compounding the physiological stresses the climbers must endure, the lower barometric pressure in winter further reduces the thin air’s already meager oxygen saturation.

Among the 14 mountains higher than 8,000 meters, about 26,250 feet, K2 was the only one that had not yet been climbed during winter. And the allure of that elusive first in the mountaineering annals drew an extraordinary number of climbers to the mountain this winter — as many as 60 from four different teams, including a commercial expedition by Seven Summit Treks. Thanks to modern social media and the ever-diminishing weight of data-transmitting satellite phones, climbers on K2 this winter season offered their pandemic-bound, adventure-starved followers around the world a virtual play-by-play of their efforts on the mountain. It was an unparalleled opportunity for armchair adventurers around the world to monitor, in close to real time, the exploits of the world’s most extreme mountaineers.

Nevertheless, while trolling the Instagram posts of this winter’s K2 climbers, a reader may be forgiven for inadvertently underappreciating the ever-present shadow of mortal risk that looms over this so-called “savage” mountain that kills about one climber for every three who reach the summit. Words like “avalanche,” “extreme exposure,” and “minus 40 Fahrenheit,” lose a bit of their punch when flanked by a selfie of our hero with a shit-eating grin on his face, offering a peace sign or a thumbs-up to the camera.

This winter’s prolific social media documentation also posed a unique challenge to some veteran mountaineering journalists who found climbers increasingly reluctant to divulge information to news outlets, saving the scoops for their own social media accounts.

“From my point of view as a journalist, the expedition was not easy to cover. From the first, some participants rationed the information that they were willing to share, avoided direct questions, and referred only to their social media, where posts had more to do with PR and selfies than with simple, factual accounts of the events as they unfolded,” wrote Angela Benavides, a mountaineering correspondent for ExplorersWeb.

After the successful Nepali team had touched the mountaintop and returned to base camp, dozens of other climbers — including the American O’Brady — remained hunkered down at base camp where they waited out a spell of bad weather before launching their own summit bids. When a narrow window of suitable weather opened up, a peloton of climbers took off up the slopes. Ascending, they found that the fixed ropes and pre-established camps had been partially buried by days of snowfall.

By Feb. 4, the last-ditch summit push of more than 20 climbers had reached Camp 3, which sits at an altitude of about 23,800 feet. Summit day was set for Feb. 5. Under the gun of another wave of bad weather that was set to roll in on Feb. 6, there was no time to rest or wait for better conditions.

Temperatures dipped to about minus 60 Fahrenheit the night of Feb. 4. And, due to limited space in the overcrowded camp, as many as seven or eight climbers crammed into each tent. Soon enough, the extreme conditions whittled down the pool of summit aspirants. Most wisely chose to abandon the climb and descend to base camp while the weather was stable.

“After mulling over whether or not to continue forward with his summit attempt, I spoke to Colin and the decision has been made. He will not be going up any farther on K2. Intuitively, something doesn’t feel right for him,” Colin O’Brady’s wife, Jenna, posted on Instagram on Feb. 4. “And for me, that’s all I needed to hear.”

But K2 is lethal at every stage of its flanks, not just the summit pyramid. Among the climbers who abandoned their summit bid at Camp 3, a Bulgarian named Atanas Skatov fell to his death during a descent along fixed ropes. “All of a sudden, in the blink of an eye, he fell down and disappeared,” a Sherpa climber named Lakpa Dendi Sherpa later recalled.

Early on the morning of Feb. 5, four climbers — Icelander John Snorri, Muhammad Ali Sadpara and Sajid Sadpara of Pakistan, and Juan Pablo Mohr of Chile — embarked for the summit. Several other climbers turned back before reaching a treacherous stretch of overhanging ice known as the “bottleneck.” Sajid Sadpara turned back at about 26,900 feet when his oxygen system malfunctioned. The three remaining climbers — including Sadpara’s father, Ali — pressed on alone. They were never seen again.

The Pakistani military launched a desperate search that dragged on for days and comprised helicopter search missions and GPS tracking and infrared sensors and satellite imagery. But it was all for naught. As of this article’s publication, no evidence of the missing climbers has been discovered.

“All three men were fathers. My heart is broken for their children and families,” O’Brady, the American climber, wrote on Instagram. “These men were remarkable humans — kind, loving, with the highest integrity. They will all be missed terribly.”

For his part, Sajid Sadpara waited at Camp 3 for a day and launched a short search of the nearby area but was forced to descend due to his deteriorating strength. According to the younger Sadpara, the missing trio did not carry a satellite phone or a walkie-talkie. Yet, they were still going strong at the moment they parted ways, leading Sadpara to suspect that a disaster must have befallen them while on the descent after a successful summit.

“I think they reached the summit,” Sadpara said in a statement two days later. “They must have had the accident on the descent because at night it started to get very windy. They have been eight thousand meters for two days, at that height in winter I have no hope that they are alive.”

“All three were strong mountaineers willing, able and with the courage to make history by standing on the top of K2 in winter conditions,” the family of John Snorri wrote in a statement posted to social media. “Our Icelandic hearts are beating with Pakistani and Chilean hearts.”

Despite the tragedy, however, this year’s K2 winter season proved that the mountain could be climbed in winter. And, as with any mountaineering achievement — no matter the extent of the human toll left in its wake — it’s likely that next winter will see even more mountaineers, and probably more commercial expeditions, on the “savage mountain.”

“While K2 is finally deserted, the significance of this recent season will echo for some time,” Benavides wrote for ExplorersWeb, adding: “In the field of expedition logistics, the Himalayan winter may have changed forever. Seven Summit Treks has shown that a fully serviced expedition on the wildest peak at the worst time of year is possible, so the market is open for future endeavors, for those willing to take the risk.”

Comments