Four fragile wooden rowboats, 10 months’ worth of provisions, and 10 courageous men set out on May 24, 1869, on an audacious expedition from the Union Pacific’s Green River Station in Wyoming en route for the “Great Unknown,” the last unexplored territory in the United States. The ragtag crew of hunters, trappers, mountain men, and American Civil War veterans were selected by John Wesley Powell, an American naturalist and Union officer who had lost his right arm during the Battle of Shiloh.

Powell had adventurism in his blood. Born in New York state in 1834, he spent his childhood bouncing around from southern Ohio to Wisconsin and Illinois. He was a teacher who took up a fascination in natural science, enduring collection trips that involved such feats as crossing Wisconsin on foot and navigating down the Mississippi by rowboat. After his war injury, he participated in the Battle of Vicksburg — which he called “the forty hardest days of my life” — and submitted a disability package that secured his future devoted to science. His lifelong investigations of nature and natural science proved enough to attract the attention of one of 33 founding members of the National Geographic Society, which promotes environmental and historical conservation.

Powell had seen to the logistics for the historic “Great Unknown” journey down the Colorado — included in the packing list were weapons and ammo, tools for the boats, clothing, and scientific instruments to measure and collect a survey of the canyons of the Green and Colorado rivers. The demands of the voyage were impossible to prepare for, and only a fortnight into their river escapades Powell recognized rough waters along the canyon ahead. He pulled his pilot boat ashore and ordered the other boats behind him to follow his lead. Unaware of his hand signals, and with the deafening rapids silencing his voice, the No Name, a 21-foot boat made of oak, descended into the winding currents.

The boat uncontrollably leaped through the waves and slammed into a jagged boulder as the three crew members desperately clung onto anything to keep their heads afloat. The men disappeared below the foam only to emerge onshore, shaken, but alive. This would be the first casualty of their journey: an unrepairable boat and months’ worth of supplies. Powell scribbled in his journal a name for the location of their costly mishap — Disaster Falls in the Canyon of Lodore. With no frame of reference to know the dangers that lay ahead, Powell’s ventures into the abyss were marking areas of the map in real time.

Three summer months spent on the river were as challenging as they were magnificent. Bracing 120-degree heat and pouring rains, the group would stop to document the landscape and climb the canyons’ cliff faces. One day Powell and another boatman, George Bradley, were hiking without a rope. Powell became trapped, unwilling and unable to move. Bradley took off his shirt, pants, and red wool long underwear and heaved the long johns over the edge. With his only arm, Powell was pulled to safety by the efforts of his fellow adventurer.

In August, during the last stretch of their impossible quest, Powell’s expedition entered the mouth of the Grand Canyon. “We are now ready to start on our way down the Great Unknown,” Powell wrote in his journal on the 13th. “Our boats, tied to a common stake, chafe each other as they are tossed by the fretful river. They ride high and buoyant, for their loads are lighter than we could desire. We have but a month’s rations remaining. The flour has been resifted through the mosquito-net sieve; the spoiled bacon has been dried and worst of it boiled; the few pounds of dried apples have been spread in the sun and reshrunken to their normal bulk. The sugar has all melted and gone on its way down the river. But we have a large sack of coffee. The lightening of the boats has this advantage: they will ride the waves better and we shall have but little to carry when we make a portage.”

Powell’s daily journal entries described the river as swift and violent; in parts the depths were deep and the canyons were narrow. He shared his experiences passing the “ancient people” or Natives that inhabited the region, and wrote of relentless rain, camping at night inside marble caves, and the canyons surrounding them as if they were trapped in a “granite prison.”

On August 29, 1869, the expedition would wind down its discoveries of mysteries at every turn and vistas of awe-striking beauty along the Colorado River, as two of the four boats and six men emerged from the bottom of the Grand Canyon, the first European descendants to explore these lands inhabited by Native Americans. Frank Goodman had quit during the first month of the journey; three others, Bill Dunn and brothers Oramel and Seneca Howland, convinced the rapids were impassable, had separated from the remaining group the day before and disappeared without a trace.

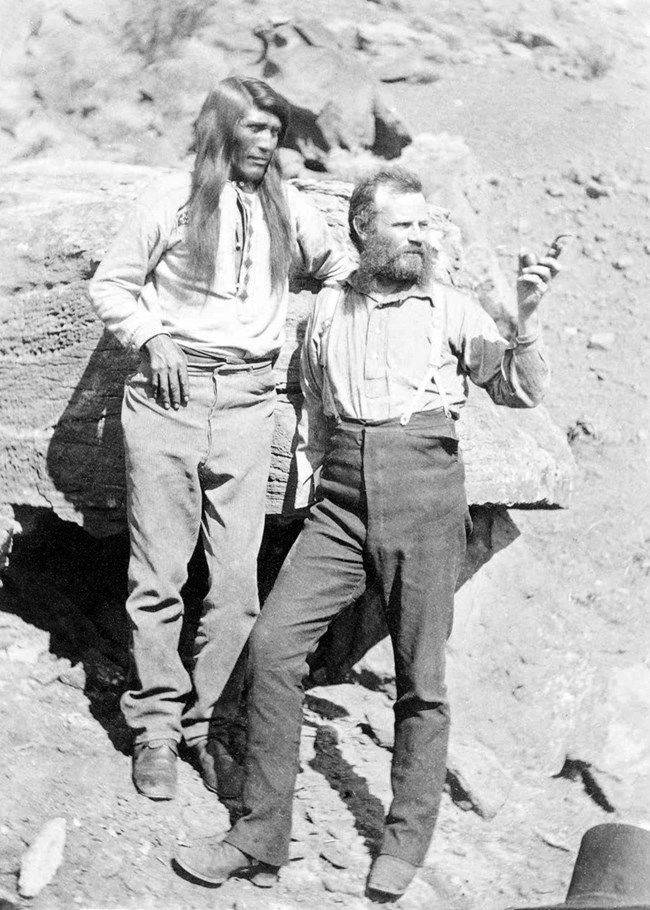

Powell earned a legendary persona for his bravado in completing the last great expedition in US history. Landmarks such as Gates of Lodore, Winnie’s Grotto, Whirlpool Canyon, Rainbow Park, and Split Mountain were named during the Powell expedition and remain so called today. The newspapers ran wild with Powell’s newfound stardom. Although no photographs were taken, Powell’s second expedition in 1871 retraced his route, and photographs taken then helped convey context to the descriptions of the Grand Canyon that had captivated the nation.

Powell served as the second director of the US Geological Survey, and many of its contributions in mapping the nation were in large part from his doing. His legacy is often a subject of debate. He is known as a fearless trailblazing explorer but also one who radically advocated for resource improvements and irrigation systems for small farms. If his ideas had been implemented, the federal water reserves and urban growth seen in the Pacific Northwest today might not have come to pass. What is certain is his contributions to 19th-century America changed the very fabric of understanding the landscape that we inhabit.

Read Next: Tom Crean: 5 Facts About the Most Badass Explorer You’ve Never Heard of

John Thornton says

John Wesley Powell article.

I enjoyed your article! FYI they refer to the one section of the canyon as ‘The Gates of Ladore”. Not that it matters.

I have followed in some of the footsteps of Mr. Powell. I have ran the Green River below Flaming Gorge to the town of Vernal, and the Yampa River. I will be further south this year. Running the Colorado.

👍😁😎