In 1912, Ishi crouched behind a bush and put his index and middle fingers to his lips. He made a sharp, high-pitched kissing sound — a rabbit distress call. To his left, Saxton T. Pope watched in amazement as a small group of rabbits came within view, then stopped and listened, all within 15 yards of these early American bowhunters.

Ishi’s repetitive calls were answered by both prey and predators, just as he predicted. From a distance, a mountain lion approached and came within 50 yards of where Pope and Ishi concealed themselves behind a bush. The curious mountain lion searched for the wounded rabbits, completely oblivious to the hunters. Pope emerged from the bush and fired five arrows at the wildcat, which dashed off into the forest when one of the arrows glanced its shoulder.

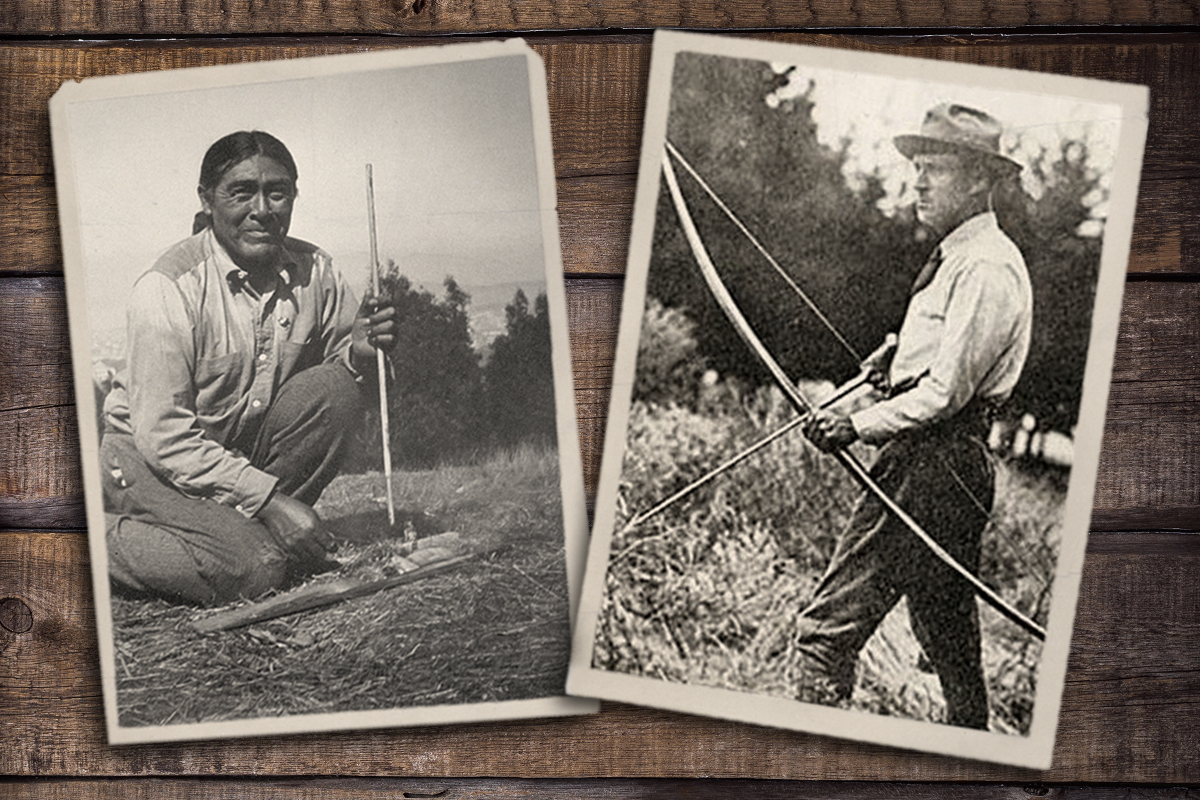

Pope, a surgeon and medical instructor by profession, only knew the calls of ducks and turkeys, but Ishi, the last of the native Yahi people, knew how to call in tree squirrels, wildcats, coyotes, and even bears. The unlikely pair of Ishi and Pope hunted together often and birthed popular American interest in the sport and practice of bowhunting.

In the classroom, Pope focused on book learning and medicine. In the outdoors — in the midst of an era when the tools for hunting involved gunpowder and rifles — Ishi was a reminder that the traditions of using a bow and arrow were worth taking into account.

Ishi, which means “man” in the Yana language of the Yahi tribe, was what Pope and others from the University of California called him. The Three Knolls Massacre in 1865 had decimated the majority of Ishi’s tribe, and for decades those who escaped stayed in hiding in Northern California. After a raid on his family’s camp in 1908 killed the last of his relatives, Ishi lived alone for the next three years.

On Aug. 29, 1911, a group of butchers stumbled upon Ishi at a slaughterhouse, scrounging for meat to feed his starving stomach. He was weak, frightened, and exhausted — a survivor. The butchers alerted the sheriff and brought him to the Oroville Jail.

His arrival was the talk of the town. Reporters traveled from Sacramento in hopes of printing a sensational headline in the next day’s newspaper; telegrams from the Department of the Interior and private citizens begged for answers. The mystery surrounding him interested anthropologists and particularly Pope, the university’s physician and medical instructor, and they arranged to bring him to the university. Pope was enamored with the Yana and Yahi people. He learned from Ishi their passion as craftsmen, particularly in the mastery of bow and arrow making. When Ishi wasn’t showing Pope his hunting practices, he spent his days on the Berkeley campus at the Museum of Anthropology.

The museum was his home for the remainder of his life, and his presence drew in newspapermen always searching for a story. His ways were intriguing — not unusual for someone who had zero previous contact with the outside world.

When a cannon was fired from several miles away, Ishi leapt from his chair, unsure of the sound he had just heard. When an excited museum visitor reached out his hand and shook Ishi’s with vigor, Ishi was left frozen, staring at his arm still in the air.

The museum’s founder, Phoebe Apperson Hearst, had acquired quite the collection of personal and donated artifacts from Egypt, Peru, Greece, and Rome — but the most fascinating attraction for many became Ishi, the only living “exhibit,” as he was viewed at the time.

Ishi demonstrated how to string a bow, make fire, and chip arrowheads made of obsidian — gifting one lucky member of the audience his creation. When some of THE daily activities grew monotonous and tiresome for Ishi, Pope recognized he could learn more from Ishi on expeditions in the surrounding mountains instead of cooped up in the museum. As their friendship blossomed, others too became curious about the knowledge of the last Yahi.

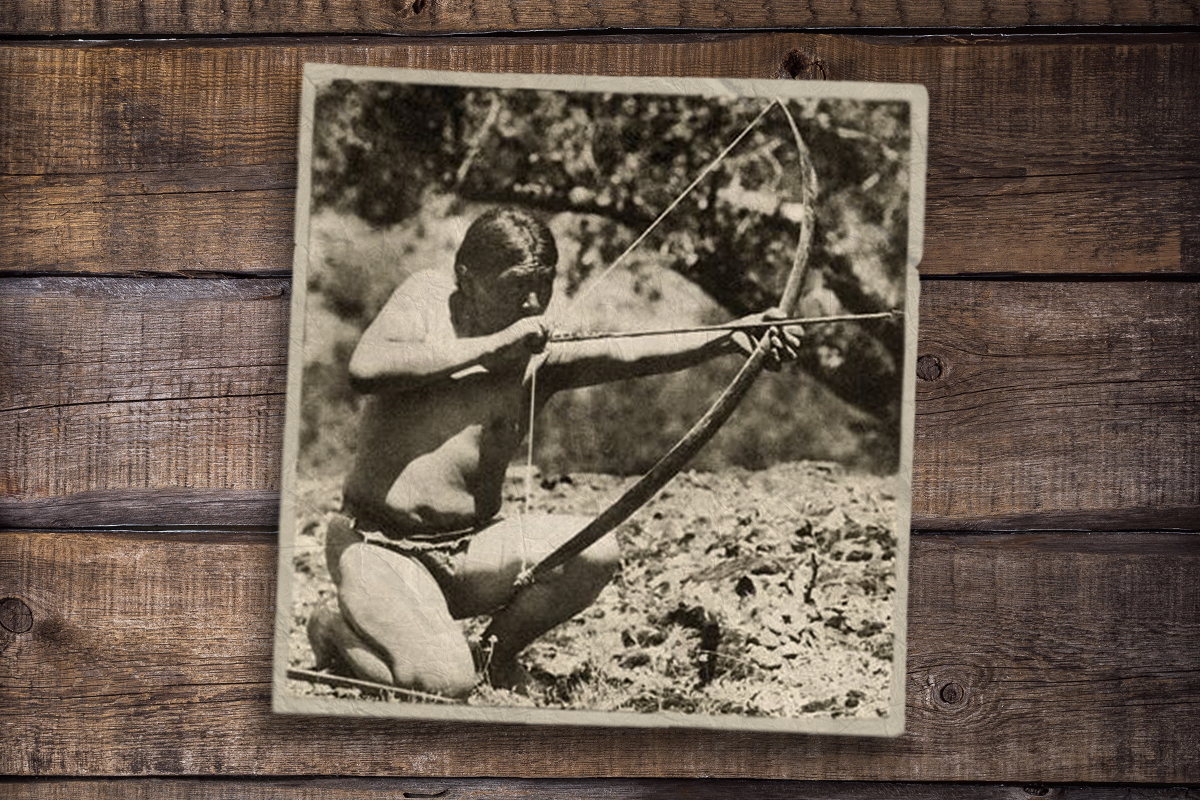

Ishi had his own hunting rituals — no fish or tobacco the day before to ensure his scent would not rouse the suspicions of the animals he chased. He wore only a loincloth, as excess materials caused too much noise in the brush. On one occasion Ishi called off a hunt because, he explained, a bluejay had already tipped off the animals in the area that a man was present.

His bow and arrows were handmade, prized possessions, treated more like a companion than a tool. These were norms for Ishi, the last wild Indian of the American frontier, and the great-grandfather of modern American bowhunting.

“Ishi was indifferent to the beauty of labor as an abstract concept,” Pope wrote. “He never fully exerted himself, but apparently had unlimited endurance.”

To the white city-living doctor and his friends accustomed to turn-of-the-century creature comforts, Ishi’s fishing, hunting, running, and climbing must have seemed like effortless forms of athleticism, but for games that involved throwing a ball he couldn’t muster the same finesse. White Americans indoctrinated with mornings filled with schoolwork had developed hand-eye coordination from a young age in games such as cricket and baseball. Skills that were shared among those involved in competitive sports clubs were absent with Ishi because he hadn’t any exposure to such games.

In 1915, at a Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, Will “Chief” Compton — who had assisted Pope by teaching him archery — met an impressionable newspaperman named Arthur Young. Young had an interest in the museum’s Japanese archery exhibit, and soon the pair became fast friends.

Ishi, Compton, Pope, and Young journeyed to North Carolina on several hunting trips, with Ishi and Compton teaching Pope and Young the mechanics of the trade. When Ishi passed away from tuberculosis in 1916, the remaining trio kept on honing their skills that led to the creation and foundation of modern bowhunting that continues to this day.

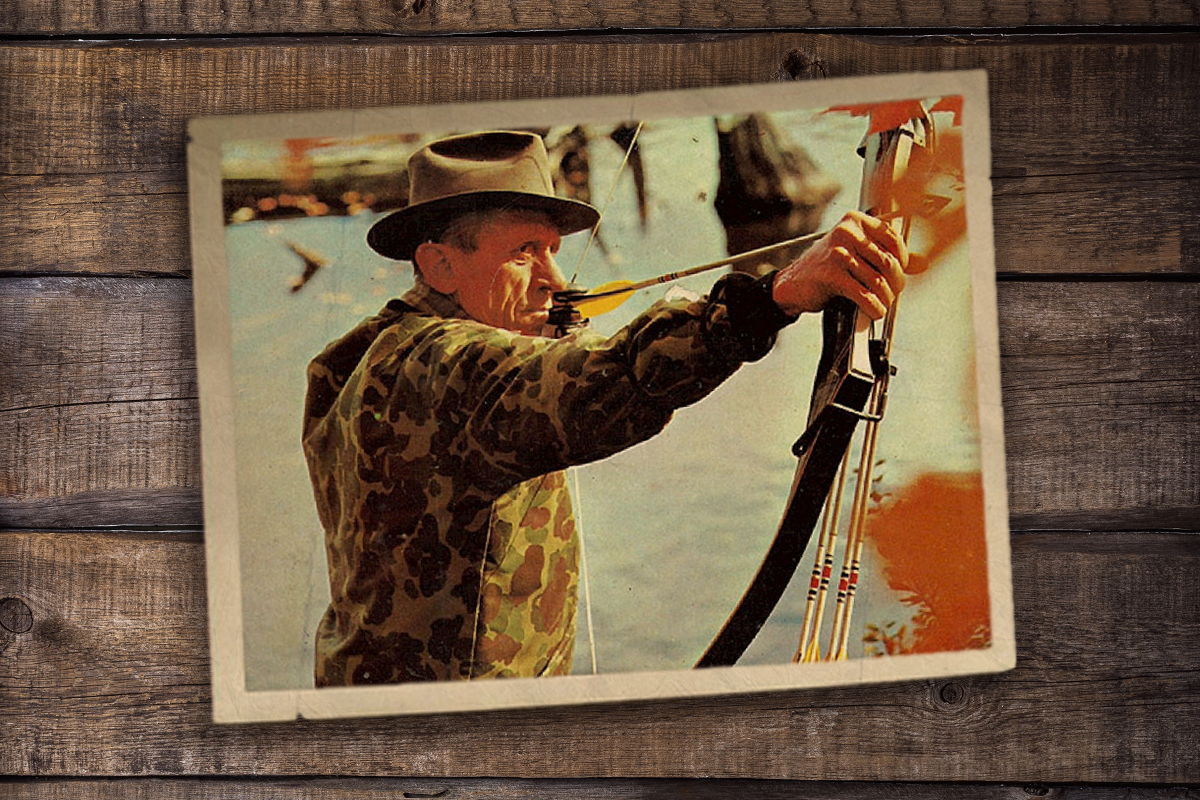

Pope and Young’s legendary 1920 expedition to Yellowstone National Park was no small feat. Their party killed five grizzly bears with bows. The very prospect had been, in Ishi’s eyes, a radical decision, since he recalled grizzlies feared nothing. Between the years 1922 and 1923, Young explored Alaska, hunting brown bear and giant moose. Emboldened by their experiences, Pope and Young ventured to their most uncharted hunting ground yet — Africa. For five months in 1925 they successfully decoyed and hunted lion, wildebeest, gazelle, eland, and other big game.

Upon returning from their voyages, they didn’t keep secrets among themselves. Pope wrote about his adventurous escapades, while Young toured the nation giving lectures on the romantic trials of bowhunting. “In the joy of hunting is intimately woven the love of the great outdoors,” Pope wrote in 1923. “The beauty of the woods, valleys, mountains, and skies feeds the soul of the sportsman where the quest of game whets only his appetite. After all, it is not the killing that brings satisfaction; it is the contest of skill and cunning. The true hunter counts his achievement in proportion to the effort involved and the fairness of the sport.”

Just like Young had grown enthralled with the idea of archery when he was first introduced to Compton in 1915, another enthusiast named Fred Bear, an automobile worker from Michigan, was inspired to join the up-and-coming industry.

He founded Bear Products Co. in 1933 and brought quality craftsmanship and innovation previously unknown on the hunting scene. Similarly, Doug Easton was just 17 years old when he completed a round of shooting at San Francisco’s Golden State Park and an older gentleman complimented him on his form. When Easton said he had learned everything he knew from the book authored by Pope, he was surprised to learn the gentleman was the author himself. Easton became a prominent figure in bowhunting and eventually introduced the advancement of aluminum arrows.

The domino effect brought bowhunting mainstream, even if the national mindset toward hunting still favored rifles and gunpowder. Through the 1940s and ’50s, as World War II and the Korean War were waged, Americans were well aware of how firepower was an effective killing instrument but still viewed a stringed bow and arrow more as toys.

Billed as “The World’s Greatest Archer,” Howard Hill dedicated his life to advancing archery in the public’s eye. He produced 23 archery films for the Warner Bros. studio and had at one time several bow records to his name, including farthest flight of an arrow at 391 yards. His weapon of choice was the longbow, and he killed more than 2,000 animals, notably a lion and an elephant.

Glenn St. Charles, an archery connoisseur and shop owner from Seattle, was instrumental in adopting the first hunting seasons under the realm of the National Field Archery Association.

With bowhunting seasons and a records program formulated by 1958, soon a separate and more robust organization called the Pope & Young Club — named after the pioneering and influential bowhunters — took shape. On Jan. 21, 1961, St. Charles took the helm as chairman with the responsibility of upholding good conservation practices, enforcing fair chase methods, and recording North American trophy animals to ensure the highest standards in bowhunting.

Sportsmen across the nation who partake in today’s bowhunting seasons must celebrate their forefathers for bringing this primal activity, rooted in survival, to the realm of sport. From its Native American Indian heritage to its early enthusiasts to the efforts of those behind the Pope & Young Club, the tradition is now deeply embedded in the culture of America.

Comments