Shad and shad fishing became real for me on a backwater hole in eastern North Carolina when my first buck hickory danced across the water on his tail like a miniaturized, silver-scaled tarpon. I was hooked more surely than that spawning fish was.

After his tap dance across that secret spot on the Tar River, a double backflip sent my spoon flying back toward my face. I did the only thing a newly addicted shad fisherman could do: I cast that spoon right back into the river and started reeling.

Hickory shad are known for their acrobatics. Sometimes called “poor man’s tarpon,” hickories earned that name fair and square. They are known to skitter and somersault in a dance so spirited it rivals the top-water theatrics of larger game fish, but on a shrunken-down scale. Pound for pound, you’d be hard-pressed to find a harder-fighting fish.

Shad-Fishing Hot Spots

Prime shad-fishing spots, also known as shad holes, often have names like “The Pipe,” “The Gut,” and “The Bend.” While they’re intentionally vague, locals know where they lie along the river as surely as the rest of us know Paris is in France.

I came across a group of young teenage anglers one afternoon in early spring as I was scouting a new-to-me shad hole. I knew they were skipping school, but the shad run is thick for only a few weeks, so I could hardly blame them. School would still be there after the spawn.

One chatty kid in a camo ball cap told me, “The best shad holes are the same places high schoolers go to have sex.”

One chatty kid in a camo ball cap told me, “The best shad holes are the same places high schoolers go to have sex.”

This might be the best description of a shad hole ever. The same natural force that drives teenagers to hike down rivers to isolated, moonlit openings in the forest drives shad up Eastern rivers. But the fish were here first. Hickory shad and American shad, which most North Carolinians know as white shad, have spawned in these rivers longer than humans have been around to witness it.

Shad spill into waterways up and down the East Coast from Florida to Nova Scotia by the millions, heading for the arcane backwaters of their births, guided by internal compasses more precise than our smartphone GPSs. When they reach their birthplace, they engage in primal mating rituals, leave behind millions of fertilized eggs, and then head back to their open-water high school of the Atlantic.

The Shadattitude

Shad don’t feed during their spawning runs. Cut one open and you’ll find a mostly empty stomach. There’s some speculation that they hit a spoon or a dart out of frustration rather than hunger, a theory supported by the number of fish hooked outside the mouth by enthusiastic anglers.

When shad actually hit a lure, it’s no guarantee you’ll land them. Their mouths are fragile and paper-thin. The shad’s frequent failure to actually grab a lure adds to the challenge of landing these scrappy fish. You can’t horse them into the boat or onto the bank. You need to play them gently, keep the line tight, and ride the fight.

When it comes to lures, shad fishing has major dividing lines.

My new teenage friends all agreed, “We like rigs with a grub jig and a trailing spoon. Anything but red.”

Tarboro resident William Redden Long, better known as W.R., long out of high school, has been shad fishing for more than half a century. He learned to fish from his father, James, who was something of a local legend among Tar River shad hunters. Long has a different opinion from that of my school-skipping buddies when it comes to shad lures.

“The colors don’t matter, but I’ve had a lot of luck on a red spoon.”

Ask a hundred shad fishermen, and you’ll get a hundred different lure recommendations.

“The colors don’t matter, but I’ve had a lot of luck on a red spoon,” Long says. To him, attitude is far more important than what you tie on the end of your line.

“I really think that, if you believe you’re going to catch one, then you’re going to catch one. I’ve gone down there and seen guys that everybody knows are good shad fishermen. They’re not doing anything different than anybody else, but they can go down there in the middle of 10 guys on the bank with belief. They cast one time and catch a fish. Because he knows he will.”

Shad on the Menu

On shad meat, there’s agreement. Both hickory and American shad are close relatives of the herring, although by general consensus, they aren’t quite as tasty. The meat is oily, pungent, and chock-full of fine bones.

According to The Oxford Companion to Food, by Alan Davidson, a legend of the Micmac tribe claimed the shad was originally a porcupine the Great Spirit turned inside out and tossed in the river. If you’ve ever picked through the 769 thin, Y-shaped bones in a shad’s body, you’re a firm believer in this story. Filleting is a complicated process, and even the most careful butcher will miss more than one sharp bone someone will find with their gums. For most, it seems like a worthless effort.

Both the taste and the profusion of bones are the reason many shad are either released, used as garden fertilizer, or tossed in the freezer to be pulled out later for summer catfish bait.

While you won’t find shad gracing the menus of any fine-dining restaurants, plenty of old-timers such as Ronnie Ellison sing the praises of shad on the table, despite the trouble. The trick is to cook them in such a way that you can eat the bones.

The trick is to cook them in such a way that you can eat the bones.

I met Ellison and some of his fishing buddies at the Battle Park boat ramp in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. He claims to have been fishing since he was “big enough to hold a rod and work a reel.” His grizzled stubble suggests that’s more than a few decades.

“The best way to cook shad is to scale ’em, gut ’em, and score ’em real deep. Then fry ’em up ’til you can crunch right through the bones,” he said. “White shad tastes better than a hickory.” That makes sense. The American shad’s scientific name is Alosa sapidissima, which translates from the Latin as “most delicious.”

Shad roe is a bone-free way to eat the run. Many shad roe recipes stretch back to hearth-powered colonial kitchens. Generations of local river rats were raised on heaping servings of shad roe. It has the texture of grits and a hint of brininess reminiscent of the ocean, where these fish spend most of their days. The roe is most often scrambled in the pan with a few eggs for breakfast. Sometimes the whole roe sack is gently dredged in seasoned flour and deep-fried — the Southern answer to how to cook everything.

Whether you eat shad or not, you can’t argue the historical importance of this fish as a food staple. Arriving at the very end of winter, when food stores were running low, spawning shad were lifesavers for the earliest Americans. Algonquin Indians tended shad weirs across inland streams. European settlers fashioned their own weirs or raided their neighbors’. For generations of North Carolinians, the return of shad in the spring meant a year’s worth of fish suppers. Families could easily scoop hundreds from the river in a single afternoon.

Shad remained an important food source in North Carolina well into the 19th century. With electricity and refrigeration slow to reach rural areas east of Raleigh, shad was one of the few meats available to poor families.

Shad and Small-Town Economies

In February 2017, the Tarboro Town Council declared hickory shad its official fish. Like many small towns along North Carolina’s eastern rivers, Tarboro is a sleepy community with a population of just over 10,000. It may be best known as a single exit on Highway 64 that vacationers zip past on their way to the Outer Banks. Yet during the peak of the shad run, that exit is backed up with kayak-topped jeeps and pickup trucks hauling johnboats. The early morning riverfront is lined with anglers, standing shoulder to shoulder slinging darts, flutter spoons, and crappie jigs like their lives depend on it.

You’ll find the same scene at other North Carolina hot spots such as Weldon, Jamesville, and Falkland, all small towns with populations counted by the dozen. Drive to Kinston, a metropolis of 20,000, and from Highway 70 you can watch scores of anglers swarming the river like the shad they’re chasing.

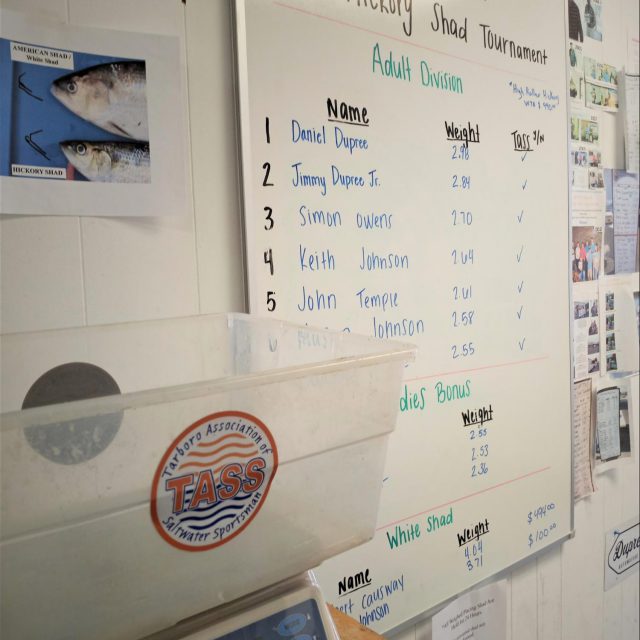

Tarboro has one thing those other eastern Carolina river towns don’t have: the Hickory Shad Tournament, sponsored by the Tarboro Association of Saltwater Sportsmen (TASS). Now in its 20th year, the tournament awards generous cash prizes and draws anglers from all over the state.

“Three pounds for a hickory is a big fish. In 20 years, we’ve only weighed three over 3 pounds.”

This year, the tournament had 85 paying entries. Tournament director Jim Dupree says that number is down compared with previous years, possibly because of COVID-19 concerns. While there may be fewer fishermen on the river, Dupree claims the shad seem bigger this year. “These are, by far, the heaviest weights ever,” he declared, eyeing the tournament leaderboard. “Three pounds for a hickory is a big fish. In 20 years, we’ve only weighed three over 3 pounds.”

This year’s tournament winner, Daniel Dupree, won more than $1,000 for his 2.98-pound buck.

The influx of anglers is good for small-town businesses, even if only for mom-and-pop restaurants, fast-food burgers, and convenience store sales of beef jerky and Gatorade.

The Great Equalizer

Lures and recipes divide shad fishermen, but that’s about it.

“When you’re down on the creek bank, everybody’s the same,” Long tells me. “My dad fished for [shad] most of his life. He would go down there in a coat and tie, sitting down there beside an old man on a bucket. They’d catch the same fish. If my dad did good, the guy on the bucket would say, ‘I’m gonna go home and get my damn tie.’ If he did good, my dad figured it was the bucket.”

People of different backgrounds, ages, genders, and races fish shad shoulder to shoulder, laughing, sharing stories, and having a good time you can see right there on the bank. Maybe the world could take some lessons from the shad run. Less from the sex-crazed high-school fish, but from the history and community that they’ve helped create in the special backwater holes in eastern North Carolina.

Read Next: The Hunter Recruitment Project Introduces Veterans to Fly Fishing

Shafik Sidiki says

Shad is now nearly extinct on the East coast. In 2021 it was hardly to be found in fish markets for sale.

Cynthia P Brown says

My 97 yr old Mother loves Shed. Born in Pittsburgh Pa. And enjoyed & loved Shed with her sister who died at 100 yrs old. We live in Chicago now. This time of the year I’m calling fish stores for ‘you got any Shed’?