In late November, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game reported the discovery of Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) in two mule deer that were killed in October by hunters in the Slate Creek drainage near Lucile in Idaho County. Now, wildlife officials have made 1,527 tags available for an emergency CWD deer hunt to determine the statewide prevalence of the disease.

This discovery of CWD was not welcome news for the state agency or hunters.

“Although CWD has been known to exist in the Western United States for over 40 years,” states a department release from Nov. 17. “This is the first time animals in Idaho have tested positive for the disease, which is fatal to deer, elk, moose, and caribou.”

The emergency CWD deer tags, which became available earlier this week, are reserved for Idaho residents and divided among 35 hunting areas. Each tag comes with strict carcass-handling instructions, like quartering and deboning the animal where it is killed, presenting the head at a check station, and recording GPS coordinates of the kill location.

Knowing that the lion’s share of deer will have moved to privately owned land by now, making hunting challenging for the public-land tagholders, the agency hopes to collect at least 775 samples.

Hunters will be allowed to keep the meat and antlers from non-infected deer.

CWD: A Nationwide Problem

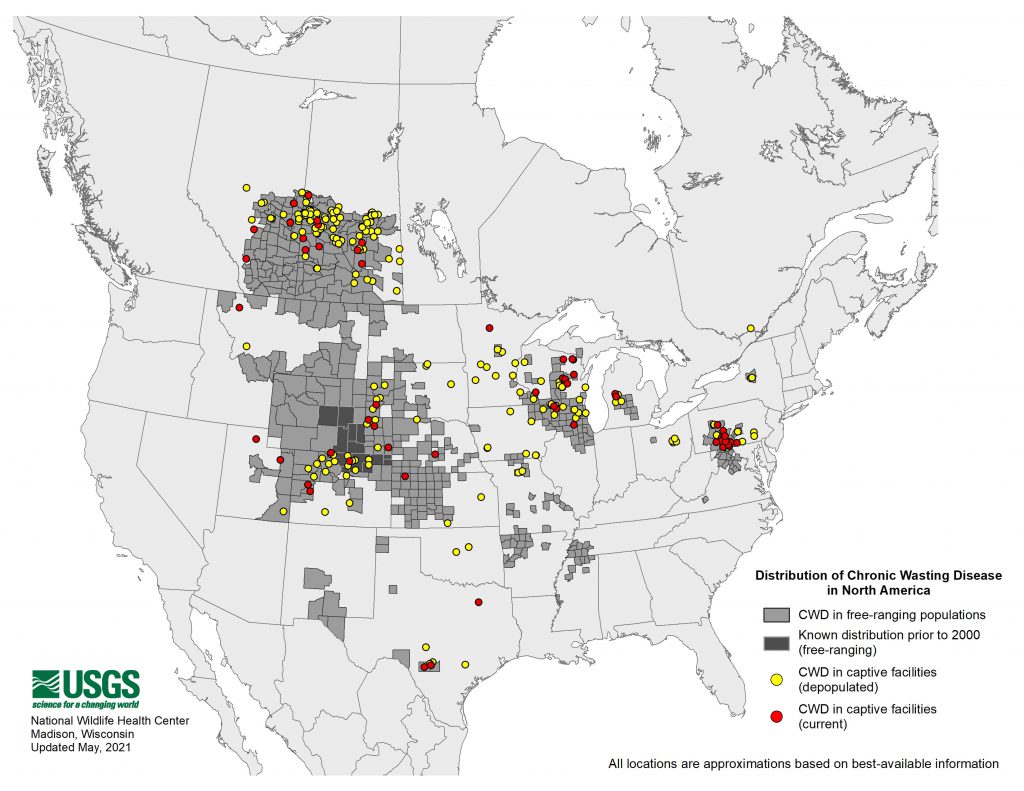

While Idaho may be the latest state to announce the discovery of CWD in its deer population, it joins a list of 26 other states in the US and four Canadian provinces that are dealing with the same challenges, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS).

The USGS reports that in some infected areas of Wyoming, Colorado, and Wisconsin, more than 40% of free-ranging cervids carry the disease.

CWD is fatal in cervids and caused by a prion, a type of infectious protein that affects the animal’s nervous system. Infected animals can spread the disease through urine and saliva.

Even though animals may show no symptoms for years after being infected, when they do, the most obvious include drastic weight loss, stumbling or lack of coordination, and a lack of fear of people.

Research has not yet identified any instances of humans contracting the disease from animals. Still, CWD is in the same family as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease) and Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease, a neurodegenerative disorder in humans.

CWD was first detected in captive deer at a Colorado research facility in the late 1960s. The first occurrence in the wild was discovered in an elk in 1981. The disease spread throughout northern Colorado and into Wyoming in the 1990s.

Today, the heaviest CWD concentration is in the Midwest and Southwest. The East Coast has avoided significant spread, only reporting a couple of small pockets. A total of more than 356 counties have reported animals with the disease.

CWD Deer: A Tough Fight Ahead

It was initially thought that CWD was limited in free-ranging wildlife and spread slowly. However, recent events have revealed CWD has been inadvertently spread widely by the sale and movement of farmed elk and deer that are infected — even with increasingly stiffer regulations and testing.

In northern Minnesota, CWD-positive carcasses from a defunct captive facility were discovered dumped on nearby public land and had already been raided by scavengers.

In Texas, three facilities outside of Dallas and San Antonio had animals test positive after they had shipped deer to more than 260 other facilities across the state.

A hunting preserve in Pennsylvania’s Northern Tier right on the New York state border\ popped for CWD, putting the Empire State at risk.

A deer farm in Wisconsin had two of its herd test positive. A subsequent investigation found that the operation had shipped 400 potentially infected deer to 40 facilities over five years.

Even with these glaring examples, it’s important to remember that the disease is naturally occurring due to a gene mutation. So, there is a chance that the 100% fatal disease originated from a genetic anomaly in a free-ranging animal.

Only 10% to 15% of all prion diseases are inherited or familial, while 85% to 90% are sporadic or acquired. That means roughly nine out of 10 cases had a spontaneous mutation or “caught” CWD from another animal.

Thanks to COVID, we’re all very familiar with contact tracing and understand just how quickly things can splinter out of control. Following the CWD to its source might be a futile effort, but many point to deer farms, which often hold animals in unnaturally tight confines, as a significant contributor to the CWD problem.

Still, so little is known about the disease that pointing fingers isn’t necessarily going to help find a solution, which so many states — now, including Idaho — are trying to develop.

Read next: Chronic Wasting Disease Outbreak: Wyoming Collects 1,000s of Samples

Comments