All firearm suppressors work the same way. When a trigger is pulled and the striker ignites a primer and sends a bullet down a firearm barrel, it’s trailed by hot and expanding gases from the combustion of primer and powder. Suppressors collect, cool, and reroute those expanding gases.

Benefits are aplenty, namely recoil reduction, less muzzle flash, and suppressed — not silenced — decibel levels, which bring many pistol and rifle reports to safe levels for human ears.

In many European countries and New Zealand, suppressors are standard kit on hunting rifles. They keep the shooter’s ears safe with the ancillary benefit of not irritating adjacent landowners. Here in the United States, suppressors were regulated federally under the National Firearms Act of 1934. They are legal to own in 42 states but require a goat rope of paperwork and fees plus a wait time of three months to more than a year while the ATF processes the sale.

As of 2020, there were more than 2 million registered suppressors in the US. Ownership has gone up by a factor of almost 10 since 2011.

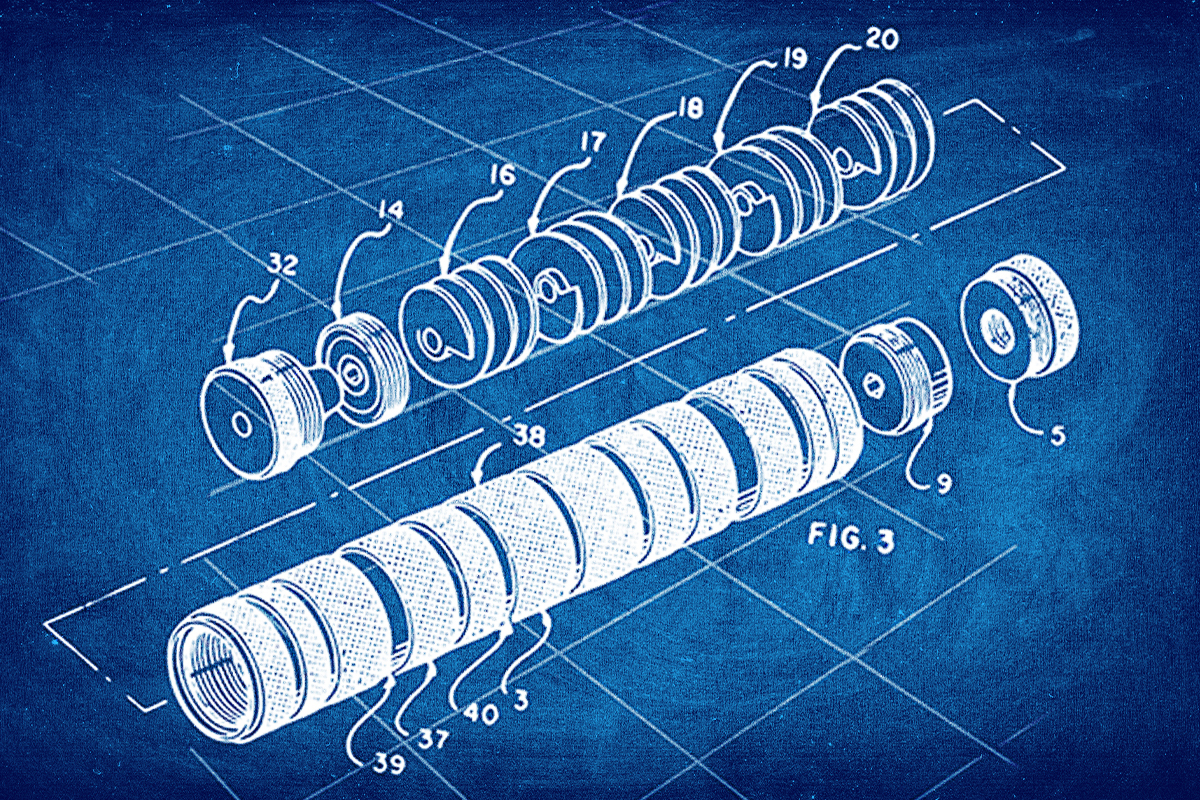

There are two basic suppressor designs: monocore and baffle stack. Both sit in a tube or can that screws onto a barrel, or muzzle device attached to the barrel.

Monocore is just like it sounds: a mono or single cylindric core with gaps, holes, channels, and vents CNC-machined through it. The elaborate machining possible on monocores means the expanded gases can be redirected within the can 10,000 ways to Sunday, making for a generally quieter report compared with less complex baffle stacks.

Baffle stacks are like sections of metal tubes within the can’s housing that, well, “baffle” the sound signature by redirecting the gases. Several baffles are usually stacked together within the can with space between them to create gaps to redirect gases before they escape. Some baffles are welded together; others stack freely. Free-stacked baffles make for a suppressor that’s much easier to clean. Suppressors are famously dirty as they collect all the gas, primer, and powder residue that would otherwise blow out the muzzle of an unsuppressed firearm.

With a suppressor, the gas and sound reroute around the baffles or core before escaping. As the unburned powder isn’t escaping and has more time to burn off within the can, the muzzle flash is reduced. As the gas itself is contained, it slows down and cools, so when it does escape, it does so with less speed and sound — hence reduced recoil and a quieter report.

It’s important to note: This does not remove the crack of a bullet breaking the speed of sound. A firearm report is really two sounds — the sound of gas bursting forth from the barrel and the sound of the bullet hitting supersonic flight. Suppressors only address the gas. It takes subsonic ammunition to remove the supersonic crack.

Still, just removing the gas report can take the ear-splitting rip of 5.56 ammo at 165 decibels down to 135 dB or less. Keep in mind, pain and permanent hearing loss start at 140 dB, and eardrums rupture at 150 dB. This is why suppressors have so much support among the shooting public. They make firearms safer, especially when combined with traditional ear protection for the larger, faster rifle calibers.

Read Next: Here Are the Reasons for the National Ammunition Shortage

Eli Richardson says

Wow, it’s so interesting to know how a firearm suppressor could reduce our shooting’s decibels. My cousin and I want to learn how to hunt, so we’re enrolling in firearm classes next week. We want to purchase hunting firearms after we finish the course, so we’ll be sure to add a suppressor to our to-buy list. Thanks for your insight on how a firearm’s suppressor helps us reduce the noise when shooting.