Gonna live while I’m alive. I’ll sleep when I’m dead.” If your friends are anything like mine, they’ve applied Bon Jovi’s infamous words on more than a few nights out in an effort to get you to stay longer. How many times have you succumbed to this coercion, not thinking of the potential consequences or even aware that any existed?

How many late nights have you pulled responding to babies that won’t sleep or work shifts that won’t end? How many evenings stretched into morning as you sat in front of your laptop in the dark, compiling one more spreadsheet or sending one last email at the expense of precious sleep, only to wake the next morning, befuddled and disoriented, telling yourself the lie that you’ll compensate for it tonight?

If you’re like me, you’ve lost count.

There are two truths to glean from the above examples. The first is that we’re not taking sleep seriously and, by extension, not getting enough of it. The second is one put forward by Matthew Walker, and it’s quite simple: the shorter your sleep, the shorter your life.

Why we sleep

Walker, a scientist at the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Human Sleep Science, has spent his career dedicated to unravelling the mysteries of sleep — why we need it, the impact it has on our bodies and our lives, and the resulting damage that comes from getting too little of it. It’s one of the last scientific mysteries; a frontier difficult to understand much less conquer, but one that he believes in crucial to the health of society in general.

As the line between our work and our personal lives become ever more blurred, and devices creep into every facet of our life, sleep is becoming something that is slowly but steadily slipping away from our day-to-day lives. According to Walker, we as a culture are currently experiencing a “catastrophic sleep-loss epidemic,” one with far-reaching consequences that we are only just beginning to grasp.

In his book, “Why We Sleep,” a four-year effort in which Walker explains his findings, Walker explores the links between lack of sleep and diseases such as Alzheimer’s, cancer, coronary artery disease, obesity, anxiety, depression, and other markers of poor mental health. His outlook isn’t positive. The collective lack of sleep we’re experiencing is having far-reaching consequences that are graver than initially thought.

Today, nearly one in two people survive on less than six hours of sleep a night, a figure that has increased five-fold since the 1940s.

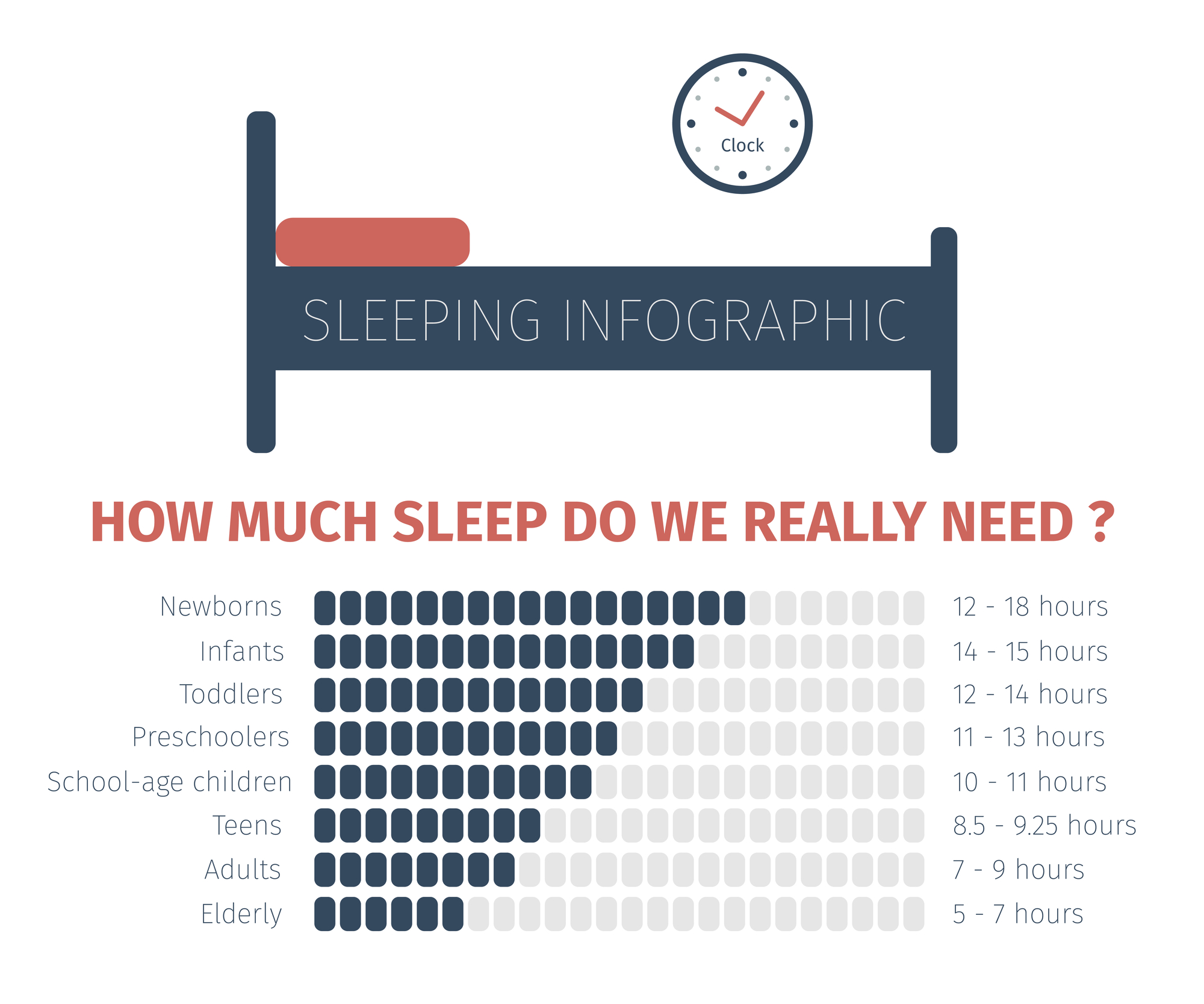

The common line of thinking is that feeling tired at work sucks, but it won’t kill me, right? Well, not exactly. Walker found that adults sleeping less than seven hours a night would be predicted to live only to their early 60s without medical treatment. As for those who drive while drowsy, the likelihood of an accident multiplies by more than 11 if you’ve had less than four hours of rest and is on par with driving drunk. And while the World Health Organization recommends eight hours of sleep per night, less than two-thirds of the working population are achieving this.

Today, nearly one in two people survive on less than six hours of sleep a night, a figure that has increased five-fold since the 1940s. But between the convalescent, post-World War II years and now, what’s changed?

There are certain obvious sleep-stealing villains that we can identify first. Cities, where 55 percent of the world’s population lives, have ceased to sleep. The setting sun is no longer a marker of a finished day. When twilight settles, nacreous street lights burst into life; apartments, homes, and offices are kept illuminated by burning bulbs, allowing people to work and stay awake long past the witching hour.

The proliferation of computers and mobile devices, and their infiltration into our homes, means that the traditional line — both physical and mental — between work and home has not only been blurred but erased completely. Whereas people used to read before bed, they now scroll through endless social media feeds. Not only does this enslave people to addictive algorithms, but the blue light emitted by mobile devices suppresses melatonin, a hormone produced in the pineal gland that regulates sleep, which shifts natural circadian rhythms by up to three hours.

But perhaps one of the biggest enemies of sleep is more clandestine. Indeed, it’s a thread woven into the cultural fabric of society: the stoic belief that sleep somehow corresponds to weakness.

How many times have you been chastised for turning in early, followed by, “Don’t be a [insert your preferred derogatory term here].” How many people have boasted about the all-nighter they pulled, how they busted their ass to cram for the next test or finish their work report? There’s pride associated with sleeplessness, a notion that longer waking hours equate to increased productivity. They wear their lack of sleep on their sleeve as a badge of honor. It’s almost embarrassing to declare that you went to sleep at 10:30 p.m. and achieved the minimum required amount of hours deemed to be healthy. Sleep eight hours? Sleep when you’re dead, man.

And it’s this attitude, Walker posits, that’s leading more and more people to an early grave.

How do we get more sleep?

With the knowledge that sleeplessness is detrimental to us as a culture, what can we do to fight against it?

Firstly, discipline yourself to create room in your schedule to sleep longer by reducing the number of all-nighters and late nights at the office. Walker suggests (somewhat radically) that we should allow students and workers to start school and work later; longer sleep correlates with higher test scores as well as increased productivity. If companies and schools rewarded people for sleeping, there’s no doubt that performance metrics would rise across the board.

On a more practical level, anyone can start by turning off their phone before bed and going to sleep at the same time every night. Think of it as you would any other healthy activity like going to the gym — not always wanted but necessary and rewarding when you go through with it.

We know that sleeping too little is bad; we know it affects us cognitively, cripples our memory, and impairs our motor skills. We even know it increases our chances of contracting life-threatening diseases. So, go ahead and turn in early tonight — after sleeping a full eight hours, you’ll wake up a better, stronger, more capable human being.

This article was originally published Sept. 17, 2018, on Coffee or Die.

Comments