A general assumption is that in order to lose weight, gain muscle, or get in better physical shape, you have to work more and work harder. While it’s true that the body must be put under stress in varying degrees for muscles to grow, what is sometimes overlooked is the importance of not working — the recovery process.

Anytime you deadlift, squat, bench press, or exceed the normal limits of daily activity, your muscles experience micro-tears. In response, your body releases inflammatory molecules called cytokines that activate the immune system to repair the muscle. Your body triggers delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) — that dull achy feeling you may experience 24 to 48 hours after the activity.

DOMS are local mechanical constraints. It’s your body telling you to stop using the muscle group and to start recovering the affected area.

When deciding which recovery techniques to use, various factors must be considered, such as age, gender, physical fitness level, and the activity that was performed.

There are a growing number of techniques being used by athletes; however, proper sleep, nutrition, and hydration are key.

Sleep

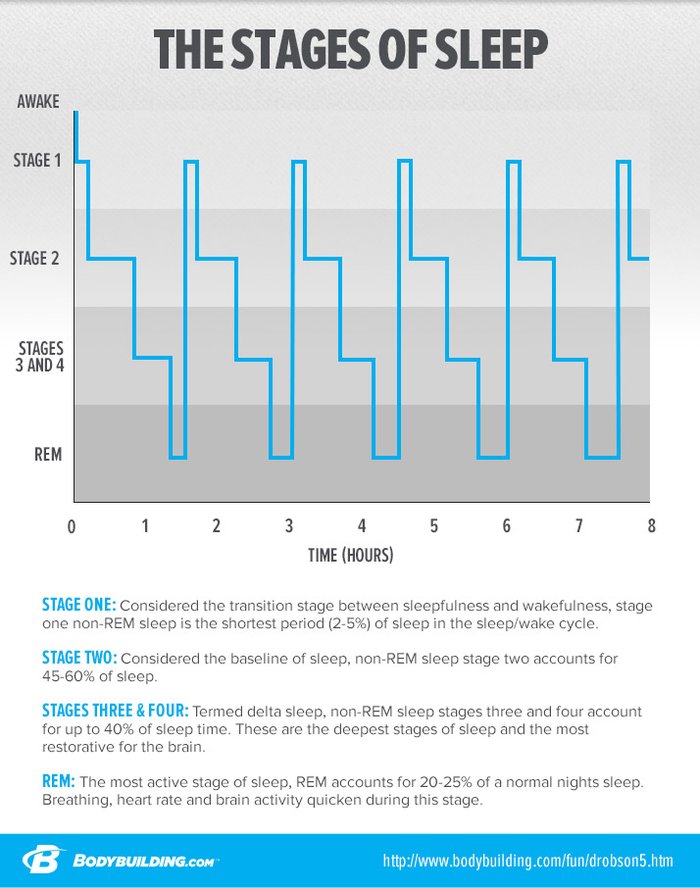

Sleep is a vital aspect of muscle repair and growth. While you sleep, your body goes into full repair mode. As you enter the N3 stage of non-REM sleep, your pituitary gland releases human growth hormone, which stimulates muscle growth and repair. Not only does sleep replenish the muscles, but it also recharges the brain — allowing for productive workouts the following day.

Eat

Exercise causes the depletion of glycogen stores and the breakdown of muscle protein. Consuming both carbohydrates and proteins within 30 minutes of your workout can improve recovery. Carbohydrates refuel your body, allowing you to restore lost energy sources, while proteins help repair and build new muscle cells. It is recommended that you consume .14 to .23 grams of protein per pound of body weight and .5 to .7 grams of carbohydrates per pound of body weight.

Hydrate

Proper hydration is imperative both during and after your workouts. During strenuous exercise, your body sweats to maintain temperature, causing fluid loss within your body. You can find your sweat rate by weighing yourself before and after exercise — then replenish your body by drink 80 to 100 percent of that loss.

Additional recovery techniques can be used in conjunction with the basics.

Active recovery

Active recovery is a way to flush out the by-products produced by exercise. To do this, choose an activity and lower the intensity to just above your resting heart rate. Some examples include brisk walking, jogging, cycling, yoga, and weightlifting at lower weights and volumes.

Hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy — such as cold water immersion (CWI), hot water immersion (HWI), and contrast water therapy (CWT) — is a common technique used by many athletes. Studies have shown that CWI is significantly better than others in reducing soreness and maintaining performance levels.

The easiest way to reap the benefits is to fill your tub with ice, run some cold water, and immerse your body for six to eight minutes. Ice baths can be painful at first, but they get easier with time.

Myofascial relief

The fascia is a thin connective tissue that covers our muscles. The purpose of myofascial relief is to break down the built-up adhesions and decrease muscle aches and stiffness.

If you’ve entered a gym in the last five years, chances are you’ve seen a foam roller — one of the most basic techniques to reduce muscle stiffness. In addition to foam rollers, sports massage and lacrosse balls have also been known to provide short-term increased range of motion and reduce soreness.

It’s easy to muster up an hour of motivation. Just turn up the music, scoop some pre-workout, and chalk up your hands. What’s not so glamorous is the time spent outside the gym — the 23 hours between training sessions. But it’s that time in between that determines your long-term results. Work hard — but recover harder.

This article was originally published Sept. 4, 2019, on Coffee or Die.

Comments